If the wine, hors d’oeuvres, and assorted sugary fantasies served up at the opening night celebration of the Boston Architectural Center’s current Designing the Rose exhibition (on view until June 1st) are anything to go by, Shakespeare & Company’s reconstruction of the 16th Century Rose Theatre at their home in Lenox, Massachusetts, will be the genuine article. (See ArtsEditor’s February 2002 piece.) Not that anyone seemed particularly interested in ancient wooden O’s when there were so many modern sugar Oh’s on offer. It may have been The Bard’s 436th birthday, but if the assembled suits and frocks were paying any homage at all to that date, it was by following the poets’ time-honored injunction to eat, drink, and be merry rather than by perusing the series of well-presented panels and models depicting the history of both the 16th Century London Rose and its prospective 21st Century American facsimile. As Sir Toby of Twelfth Night might have said, “Dost thou think that because thou art virtuous and give donations to the arts, there shall be no more cakes and fine wines?” Especially when one has paid $150 for a ticket.

Accordingly, the glaze on the pastries was soon mirrored in the eyes of the attendees, especially after Shakespeare & Company artistic director Tina Packer’s interesting, energetic, but ultimately rather sprawling and overly long talk on the image of the rose through history. If such talks be the food of donation, we can only hope that Packer did not make the mistake of giving her audience “an excess of it; that, surfeiting, the appetite may sicken and so die” (Twelfth Night, I, i). For the Lenox Rose currently stands a mere 18 inches above the ground, and a cool $30 million is needed to raise it to its full 28 1/2 feet and renovate the surrounding buildings to create a “Renaissance village.” Every Rose, one might say, has a thorn.

But why bother recreating the Rose after over four hundred years? Packer’s answer, as ArtsEditor has previously reported, is to allow modern audiences to experience Shakespeare as the Elizabethans did—out of doors, up close, densely packed in, and, for at least half the audience, standing up. All of which sounds like great fun, no doubt—as long as it doesn’t rain. But the question is, would anyone visit the Rose twice? Would anyone genuinely enjoy rocking on his heels for three hours plus, squeezed between two sweating Falstaffs and almost blinded by some gigantic Caliban standing directly in front of him? Isn’t the Rose doomed to become a once-in-a-lifetime curio for culture tourists in the modern thespian world of upholstered armchairs, air-conditioning, perfect sight-lines, and elaborate sets?

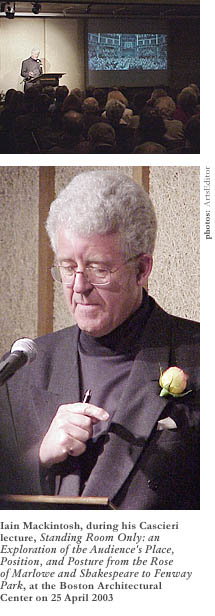

Enter, two days later, Iain Mackintosh, an eminent theater historian and designer involved in the Rose Playhouse USA Project, who dedicated his whole Cascieri lecture to this very topic. In his rather precious, unnecessarily academic way, he argued that theaters lost something significant when they lost their “groundlings” (standing patrons). Namely, they lost a certain rapport, a certain interaction between audience and actor, of the kind demonstrated in the film Shakespeare in Love (in which the original Rose Theatre is depicted). They lost the vibrancy and energy that can only be produced and sustained by a densely packed and physically uncomfortable crowd. Watching a play, when English theatres reopened after the Restoration, became less like watching a sports game and more like watching a movie.

In fact, even watching a sports game is becoming ever more like watching a movie, according to Mackintosh. Citing the figures for successive sports stadia built over the ages, he demonstrated how even they have become inexorably bigger, and inexorably less densely populated. The national stadium in Scotland, Hampden Park, which once held up to 150,000 people, can now only hold about 60,000 because of the introduction of seating. And the same is true of English soccer grounds, which were required to become all-seater after the Hillsborough disaster of 1989, in which 96 Liverpool fans were crushed to death after police let too many people into a standing area behind the goal. And, although Mackintosh neglected to make this point, almost everyone agrees that some of the atmosphere of the soccer ground was lost as a result.

But, to get back to our previous question, why should watching a play be like watching a sports match? Well, one reason is that actors apparently appreciate a raucous, responsive, volatile audience. But what about the audience itself? Be warned: there will be no bathrooms in the Rose, since that would be too anachronistic. Patrons caught short will have to elbow their way out of the theatre in order, as it were, to release the pressure. (According to Mackintosh, the Elizabethans simply relieved themselves on the theater floor—even those in the balconies, with the result that the urine would drip on the heads of those below. Would a Rose by any other name smell as foul?)

Mackintosh insists that a significant number of people would prefer to stand at the theater than sit—provided that standing were significantly (six to eight times) cheaper than sitting. Even he, a sixty-five-year-old man, claims to feel the attraction, citing the time when he and his wife stood at the Covent Garden opera house in London for more than four hours, all the time reveling in the knowledge that the people sitting directly in front of him had paid ten times more for their tickets than he had.

Mackintosh insists that a significant number of people would prefer to stand at the theater than sit—provided that standing were significantly (six to eight times) cheaper than sitting. Even he, a sixty-five-year-old man, claims to feel the attraction, citing the time when he and his wife stood at the Covent Garden opera house in London for more than four hours, all the time reveling in the knowledge that the people sitting directly in front of him had paid ten times more for their tickets than he had.

But surely your average opera-goer would rather pay ten times as much as Mackintosh in exchange for a seat? After all, money is not usually much of an object for such people; indeed, critics often deride opera houses for being nothing but meeting places for the wealthy and pretentious. (Nor did a British ex-cabinet minister do Covent Garden’s image any favors when he famously described the homeless as “the people you step over when you come out of the opera.”) I myself once stood at the Vienna Opera when I was eking my way around Europe as a student, but on no account would I do it again. My nineteen-year-old legs felt like ninety-year-old ones by the end of the fourth act and I’d have given my kingdom for a seat if only I’d had one. Perhaps I just wasn’t sufficiently enthused by the spectacle. I admit I’m not much of an opera buff, but I should also admit that I often find myself resenting even my favorite rock bands if they come back out for more than one encore. And even Mackintosh admitted to having sat on the floor a couple of times.

Nor can one imagine Mackintosh engaging in much repartee with the actors at the reconstructed Rose. He just seems too middle class to heckle anyone. True, his highly self-referential speech did depict him as something of an everyman, equally at ease chatting in London’s famously exclusive Garrick Club with former deputy leaders of the British Labor Party and shouting at football matches in his native Edinburgh. But, then again, his soccer-going stories were all recalled from childhood. Since then he has lost all trace of a Scottish accent and apparently all interest in the common man’s beautiful game. True, he also expressed the unlikely wish that Shakespeare & Company’s Renaissance village could include a few brothels, as the Bankside of the original Rose did (the ladies of which were probably the only women to attend the theater). But, then again, he did so with the emphatically elitist remark that “one should never underestimate the link between Apollo and Dionysus.” I know for a fact that if he made such a remark on the streets of his native city, he would be lucky to avoid getting into a fight.

The fact is, it seems to me, that your average middle-aged, upper middle-class theater-goer—the kind that made up Mackintosh’s audience, for example—just isn’t going to shout back at the actors, even if they are standing directly in front of the stage. You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make it spit. Theatrical experience can no doubt affect the way an audience thinks about some of life’s issues, but I sincerely doubt that an evening as a Rose groundling could overcome a lifetime of stand-offish social conditioning and reverse someone’s preference for ever larger, ever more private personal space.

Mackintosh’s response to such doubts was ultimately rather ambiguous. In some remarks he seemed to be embarked on a crusade to get theater-goers to stand beside—or, at least, sit crushed up against—their neighbors in the name of encouraging more social interaction. Apparently, such enforced contact with strangers has resulted in more than one marriage for acquaintances of Mackintosh. Yet, at other times, he seemed to advocate standing room simply in the name of democracy—on the grounds that not everyone wants the same kind of theatrical experience.

But who is this “everyone”? The traditional dressed-up patrons of the arts—or the whole of society? In championing cheap standing tickets, is Mackintosh in fact hoping to make the theater once more appealing and accessible to all sectors of the population, as it did in Shakespeare’s day?

Apparently not. When I put this question to him after his talk, Mackintosh’s rather cursory and patronizing response was to eschew any discussion of theater-going’s relations to class, preferring to foresee the standing areas of theaters being populated by a high proportion of “young people.” On the other hand, I suspect that he only said that because he thought it was what I wanted to hear, me appearing not dissimilar to one of his students. I say that because he then went on to liken himself to an actor, who has to gear his speeches precisely to the particular character and mood of his audience. I’m afraid my irritation at such air and graces rather ruined my appreciation of the fine complimentary cakes with which the BAC saw fit to round off the evening. I was left muttering into my butter-cream that if going to the new Rose Theatre meant being crushed up against people like him, this young person would always elect to stay in his comfortable armchair at home and watch a soccer game on FOX Sports World.

But it wasn’t true, of course. I can’t afford the subscription fee.