Another mighty timber post was erected—metaphorically, at least—in Shakespeare & Company’s ambitious efforts to reconstruct an authentic Renaissance playhouse on its campus at Lenox in western Massachusetts. In addition to receiving a grant in excess of $100,000 from the National Endowment for the Humanities, in December 2001 the Rose Playhouse USA Project also received donations of $1,000,000 from both an anonymous individual and from Congress. And the legitimacy and publicity generated by that latter grant will surely lend an unstoppable momentum to fundraising efforts for the additional 20 to 24 million dollars the project is expected to cost. Not surprisingly, then, the company went into 2002 feeling jubilant (if a little hung over).

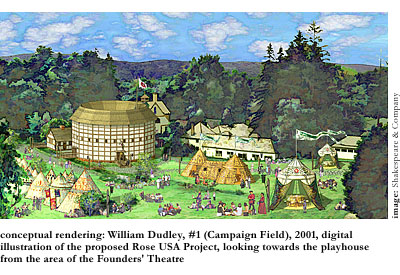

The brainchild of Shakespeare & Company’s founder and artist director, Tina Packer, the Rose Playhouse USA Project will take advantage of the recent excavation and archeological survey of the original Rose Theatre, built in 1587 on the south bank of the Thames in London, to attempt to recreate an exact facsimile of it. The project will also involve the conversion of many existing historical buildings on the Lenox site into a “Renaissance village,” and is expected to lure thousands of tourists from around the world every year. Of course, this is not the first time such a project has been undertaken. The Globe Theatre has already been recreated a few hundred yards from the site of the Rose excavation. And that might be seen to raise the question of why we can’t just leave the Re-Renaissance at that. After all, the Globe is indisputably the Shakespearean playhouse, the home to all of his later, best known plays. Why, then, reconstruct the smaller predecessor, which the Globe put out of business in 1606? Isn’t the Rose USA destined to be merely a second-best imitation of the definitive Shakespearean experience at the Globe: a consolation for those New England Bardophiles for whom the Atlantic Ocean remains as insurmountable a hurdle as it was for the average Old Englander?

I have to say that that was my initial reaction. Yet, having looked more closely at Shakespeare & Company’s plans I have become convinced of the contrary. First, the Rose possesses enough historical significance in itself to emerge from the Globe’s elliptical shadow. It was only the fifth theatre built in England, as the Renaissance spread northwards from the continent, and it was home not only to Shakespeare’s earliest plays, including Henry VI and Titus Andronicus but also to the plays of other important Elizabethan dramatists such as Marlowe, Jonson, and Fletcher.

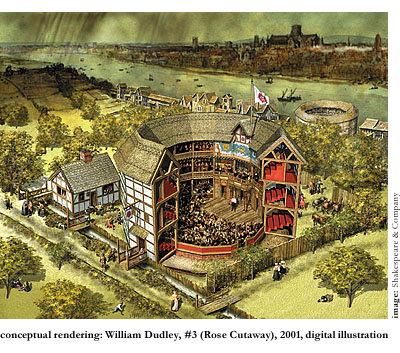

Secondly, there is much more documentary evidence in existence pertaining to the Rose, not only from the archeological survey (the results of which are pending) but also from the diaries of both its original owner and builder, Philip Henslowe, and his son-in-law, a leading actor there. The Globe, by contrast, was built largely from conjecture, and the Rose survey—which was only beginning as the Globe was completed in 1997—has revealed that some of the guesswork of the academics and architects involved in the reconstruction was wrong. For example, the shape of the stage, which had been assumed to be rectangular, turns out to have been hexagonal, projecting out into the “groundlings”: the spectators who stood immediately in front of the stage like fans at a modern rock concert. Hence, the Rose project will give the Globe team, who have readily agreed to collaborate on it, a chance to improve on their original effort: a second try at perfect authenticity.

Yet, still, won’t that cherished quality—authenticity—remain as elusive as the answers to Hamlet’s existential questions? After all, three thousand miles and four hundred years is a considerable remove from Elizabethan London. Even if the reconstruction employs, as is promised, entirely original materials and building methods, can it really attain any more authenticity than a Disneyland mock-up of a Bavarian castle? Well, it seems to me that the precise meaning of “authenticity” here is quite as elusive as the quality itself. Perhaps it has something to do with the context into which something is placed—a vast theme park in Orlando serving as the paragon of inappropriateness here. If that is true then one might well be reassured by the argument advanced, in correspondence, by Mary Guzzy, the project’s director: viz. that modern Lenox bears considerably more resemblance to 16th Century “Banksyde” than does 21st Century Bankside which, though still the artistic hub of London, is now emphatically urban, in contrast to the semi-rural quality it still preserved in Shakespeare’s day. As a friend of mine once remarked, the Globe does look rather like an overgrown doll’s house, with its half-timbered walls and thatched roof, surrounded by the dwarfing steel and concrete structures of a modern capital city.

But what about the aforementioned Renaissance village? Mightn’t that compromise the integrity of the playhouse itself by offering free plastic Falstaffs with every Merry Repast in Ye Olde McDonald & Sons? Guzzy is emphatic in her determination to avoid such a scenario, and passed on a similar promise from Packer not to populate the village with “actors in pumpkin pants strolling about playing lutes.” Their intention is to create something more challenging than a mere “Ren fest” (of which there are already a number in existence). There will be snacks and souvenirs on sale but the idea is to make most of the village buildings into working businesses that make and sell the things the company needs: a smithy for swords and armor, a printing press for programs. Moreover, the whole Rose Village experience will be centered on the exhibition center, which will do its best to recreate for visitors the Renaissance world of ideas: the particular historical, social, spiritual, political, and philosophical backdrop of Shakespeare’s drama. Of course, this is an impossibly lofty aspiration in a time where medieval superstition and closed-mindedness are just laughable stories rather than living demons (as it were) which need to be slain. Nevertheless, one can surely go some way towards it—especially since, as Guzzy points out, there are certain parallels between the paradigm-shifting events and innovations of the Renaissance and those of modern times. And one can thereby both educate the visitors and deepen their understanding and appreciation of what they witness in the playhouse itself.

For the Rose is not intended to be a museum piece, to walk around but not to touch. Shakespeare & Company is, after all, a theater company, and the primary purpose of building the Rose is to allow modern American audiences to experience Shakespearean drama as the Elizabethans did: in an small (the Rose is only 72 feet in diameter), circular theater whose resonance and intimacy arguably provided for a much more intense, visceral experience than do modern theatres. And, crucially, such an environment has the effect of focusing the audience’s attention on Shakespeare’s greatest asset—his language. Nothing—elaborate sets, quirky costumes, or sheer physical distance—will stand between the audience and the words the actors deliver. That is not to say, admits Guzzy, that there is no other legitimate way to experience Shakespeare, but this linguistic emphasis is rarely seen, and has been at the core of Shakespeare & Company’s “aesthetic” ever since Packer founded it in 1978. Moreover, the company’s commitment to “intellectual rigor and artistic aspiration” is impressive; the National Endowment for the Humanities grant, for example, will be spent on a meeting, next summer, of scholars, educators, and actors to further explore how Shakespeare’s plays were originally performed. And, indeed, this is only one aspect of the Rose USA’s ancillary educational project, which aims to provide a vast range of resources for local schoolchildren and their teachers.

Hence the Rose will provide a rare and potentially thrilling experience to the maximum of 600 visitors permitted to brave either the elements, as groundlings, or the hard benches in the three stories of covered, encircling galleries (fire regulations and the greater average size of the modern American compared to the Renaissance Londoner requiring this reduction from the 1,500 capacity of the original Rose). Yet it seems to me that there is one final worry not so easily dispelled. For, in thus avoiding the Scylla of theme-parkism, isn’t the project in danger of steering too close to the Charybdis of elitism? Won’t the average American be put off by such uncompromising dedication to showcasing the impenetrable poetry of their high school tormentor? Guzzy argues passionately that everyone can and should have the opportunity to appreciate great theatre (and hopefully the Rose’s ticket prices will reflect that conviction). She also insists that Shakespeare is for the masses: that there is something in his plays for everyone. And no doubt the outstanding success of the original Globe theatre is ample proof, if any be needed, that the lure of Shakespeare did indeed transcend social classes. Yet, all that archaic language, all that Classical imagery…ah, there’s the rub (as Hamlet would put it). For all Shakespeare & Company’s wishful thinking about the general public’s appetite for “depth and authenticity of experience,” won’t the New English Rose, in reality, end up either dumbing down or relying on the generous donations of a steady stream of wealthy, well-educated, Berkshires culture-vultures to preserve it from following the original Rose into bankruptcy?

That, it seems to me, is the question. Alas, we will have to wait a good five years before the answers begin to be provided since construction is not expected to be completed until 2007. In the meantime, however, one can only applaud the ambition, optimism, integrity, and “Elizabethan energy” with which Packer’s ever-expanding company has thrown itself into the project. That gloomy, procrastinating Prince of Denmark could surely have learned a lot from their example.