One of the more obscure pieces of public sculpture in Boston, accessible to pedestrians who stumble upon it accidentally or go back to it for a second look after stumbling upon it accidentally, must be the monument to Leif Eriksson (about AD 970-1020) that adorns the head of the Commonwealth Avenue Mall, just on the downtown side of Kenmore Square. Though far from Eriksson’s landing place several hundred miles from here in the Maritimes of Canada, the Norse explorer looks confident that he belongs in Boston, and strangely proud to be standing so close to the maniacal traffic headed toward Storrow Drive from Park Drive in the Fens. Granted, he does have the honor of being the last in that mile-long line of sailormen and statesmen whose likenesses decorate the tree-canopied Mall. Trimly proportioned, Roman-nosed, and disarmingly dressed in a skin-tight chain mail shirt and a short pleated kilt the lean and handsome explorer looks west from his pedestal, high above the ship-shaped, flower-bedecked base of the statue, spy-glass at ease in the right hand that rests on his hip, left hand shielding his eyes from the setting sun—as if to get a better look at the green walls of Fenway Park before heading inland for bigger adventures.

It must have been a great place for such a statue, back when Eriksson overlooked the granite-banked Muddy River at its mouth in the Charles, at the northern clasp of the Emerald Necklace, before the concrete demands of cars cluttered the space with roadways. Maybe, inadvertently, it still is a great place for the piece, given the unintentionally surreal interactions it has with its revised environment and the trail of historical curiosities behind it. Who would have known, for example, that Anne Whitney, the creator of the monument, worked at 30 Ipswich Street, the large studio building just on the other side of the nearby Mass Pike, now standing in isolation from the Back Bay neighborhood it belonged to then. At least until the turn of the 20th Century, with retired literati and abolitionists from the Civil War era roaming the greensward in their tweed vests, and with their inspired daughters fighting on the front for the rights to vote and make art, it must have been nearly bohemian, in a bluestocking Bostonian way. Many of the women artists (and not just Whitney) who are represented in A Studio of Her Own: Women Artists in Boston 1870-1940, now showing at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, lived in this area, comprising a kind of leisure-class artists’ colony. Women weren’t winning their way into boardrooms yet. But some of those with the money to hire Irish- and African-American women to do the washing and cooking, while their husbands were wielding their power downtown on State Street, walked boldly through the doors of art classes, where only men had been allowed before—life drawing, sculpture, printmaking, painting, sculpture, and glass-staining classes.

It must have been a great place for such a statue, back when Eriksson overlooked the granite-banked Muddy River at its mouth in the Charles, at the northern clasp of the Emerald Necklace, before the concrete demands of cars cluttered the space with roadways. Maybe, inadvertently, it still is a great place for the piece, given the unintentionally surreal interactions it has with its revised environment and the trail of historical curiosities behind it. Who would have known, for example, that Anne Whitney, the creator of the monument, worked at 30 Ipswich Street, the large studio building just on the other side of the nearby Mass Pike, now standing in isolation from the Back Bay neighborhood it belonged to then. At least until the turn of the 20th Century, with retired literati and abolitionists from the Civil War era roaming the greensward in their tweed vests, and with their inspired daughters fighting on the front for the rights to vote and make art, it must have been nearly bohemian, in a bluestocking Bostonian way. Many of the women artists (and not just Whitney) who are represented in A Studio of Her Own: Women Artists in Boston 1870-1940, now showing at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, lived in this area, comprising a kind of leisure-class artists’ colony. Women weren’t winning their way into boardrooms yet. But some of those with the money to hire Irish- and African-American women to do the washing and cooking, while their husbands were wielding their power downtown on State Street, walked boldly through the doors of art classes, where only men had been allowed before—life drawing, sculpture, printmaking, painting, sculpture, and glass-staining classes.

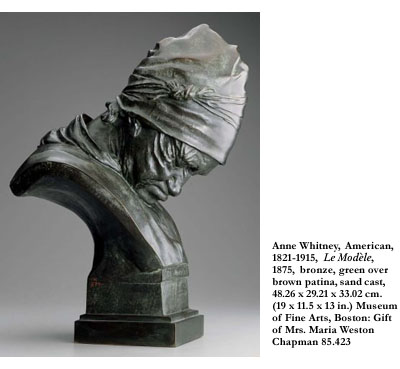

Not even a plaster cast of the Leif Eriksson statue appears in the MFA exhibit. (Selected plaster casts of Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller’s Emancipation, on Columbus Avenue in the South End, do.) But a couple of Anne Whitney’s smaller sculptures appear in the first of the three periods represented in the show—the Arts and Crafts period—and one of them, ironically titled Le Modèle, gives gravity to its gallery. Anything but an Ingre-like monument to a French idea of feminine beauty one might expect from such a title, this rough bronze bust depicts, with uncommon sympathy, the dream-heavy head of an ordinary woman of African descent and apparently modest means. She sleeps so deeply, upright in her chair in the washroom or kitchen of the Back Bay mansion she must work in, that her dark bronze chin attaches to her dark bronze breastbone. Her snoring is almost audible. Muscles gone slack, her relaxed lower lip pushes forward in slobber-free surrender to the lullaby within.

Maybe she’s not really sleeping on the job in a Marlborough Street manse—maybe she’s parked on a park bench in the Commonwealth Avenue Mall between Exeter and Fairfield Streets, pausing to refresh herself for the long walk home to Lower Roxbury or the South End. There’s only her head to go on, with educated guesses. If she “dreams of tigers in red weather,” like the sailor in the Wallace Stevens poem, so be it. But it’s more likely that she dreams of disembodied mops dancing after hours in pre-Raphaelite parlors, of bawling nursemaids’ babes with orange rubber necks and webbed feet like the ducks in the Public Garden. Her great bandanna, with oxidized-green creases just like those in the wrinkles of the crow’s feet at the corners of her mouth and her eyes, bears a dynamically depicted knot above one temple that invites an ornery tug, if only to make sure it’s really metal, that would send the vigilant gallery guard into an understandable frenzy. Same for the fray of stray locks curling onto her neck from the bandanna in back. Head tilted completely forward, she’s a surprising anti-monument, impossible to admire full in the face the way one might a crease-featured bust by Rodin, say. Le Modèle is Whitney’s bold statement about the dreariness of daily labors, especially women’s daily labors, more particularly working class women’s daily labors, and climactically black women’s daily labors. Very quietly centering the first room in the show, she speaks to a history larger than (though no less a complicated part of) Boston’s. This, after all, has been both the northern states’ center of the abolitionist movement before the Civil War and the site of the South Boston busing riots of the 1970s.

The other works in the small Arts and Crafts gallery, representing loosely the period between the Civil War and the 20th Century, include finely illustrated posters advertising books by women authors and announcing benefits for the New England Hospital for Women and Children and the Women’s Educational Industrial Union; paintings by Sarah Wyman Whitman in the adventurously subdued Turner/Whistler style; and the first of several curious self-portraits in the show—the daunting self-portrait by Ellen Day Hale, done in the dark style of Manet. A caption in the gallery reminds us that Arts and Crafts work, most of it in the domestic-arts genres lightly represented here, was done in reaction to the cold gray effects of post-Civil War mass-production, when, for example, store-bought clothes of standardized sizes were rendering the hearth-side loom obsolete. One might forget, otherwise, how unusual it still must have been, in 1880-something, for women to make art professionally—even though it is women who had always been pegged as the decorative gender, interested mainly in image.

The second and larger chronological section of the exhibit offers a wide variety of works, mostly paintings and drawings, by disciples of the Boston School of painting, which survived in its own purple shroud until brought into a glaring light by the bombs of the First World War bursting in air. Women artists of this period did not seem to be speaking as explicitly to feminist themes as some of the Arts and Craftswomen were, at least not in Boston. But the many representations of women in these works, however ornate, remote, and indolent the painted ladies may be, nevertheless do illustrate a growing independence for women. The painters’ dual embrace of painting and of womanhood comes through in deftly worked canvases, and the figured women’s varying states of absorption, excitement, and sensual intoxication seem—cumulatively if not individually—to speak for the newly valued lives, or perhaps the newly recognized potential, of women. True, the Boston School subjects are the more refined, less worldly Brahmin women who had the time and training to make art. Toward the turn of the 20th Century, shunning what a caption on the gallery wall calls “intense emotion, social realism, and political commentary,” and ignoring the subject matter found outside of a certain circumscribed circle, the female Boston artists of this period went at least partway along the lush and fruity pre-Raphaelite route, doing (according to another interpretive caption) “impeccably arranged still-lifes and figurative studies of women in tasteful interior.” Gender was the implied, softly peddled topic, and it wasn’t mixed with class and race like it would be today. Far from the mills of Lowell, where French-Canadian farm girls cranked out the cloth for the capitalists, these artists would have been more likely to title a piece Le Modèle with class-conscious admiration for European culture than with the irony Whitney had in mind.

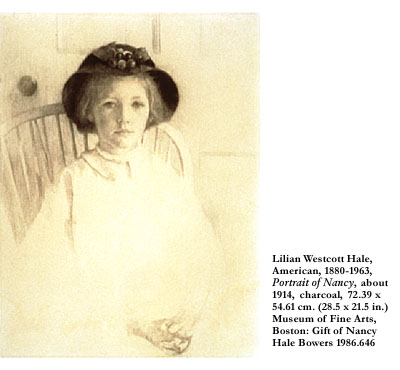

The paintings and drawings of Lilian Westcott Hale serve as firm yet florid examples of the Boston School. Although brave in their portrayal of women in states of aesthetic rapture—as if, reading about Keats’ nightingale, “a drowsy numbness pained their sense, /As if of hemlock [they] had drunk, /Or emptied some dull opiate to the drain /Five minutes hence, and Lethe-ward had sunk.” Though independent of their cane-and-top hat gentlemen companions who may have treated them the way Torvald did Nora in Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, patronizingly calling her “my little chickadee,” they nevertheless exemplify this mannered moment of upper-class American life, when the barons were building their empires in Manhattan and the Harvard-bound boys of the Back Bay were boarding at Exeter.

Hale’s drawing of her daughter at age 10, titled Portrait of Nancy (The Cherry Hat), reveals a girl coming of age in this erudite environment, by the looks of her with no shortage of self-confidence and pride. Quarter-turned in a wooden chair, she looks out from the picture with her gaze lowered an iota or two, prim and pretty (and extremely sensible and cultivated) in a fashionable hat mounted with a sprig of cherries (freshly picked, could they be?) at the forehead, her clipped hair cut high on the neck, clear eyes full of mote-free thought. This could be seen as a representative image of that state of intimate detachment that Bostonians are known for—reserved and intense and yet hoping to be admired for their refinement and eccentricity. Wearing a dress with a neat and modest collar, Nancy centers her chair, whose vertical wooden bars support the girl’s erect posture and intelligent poise as much as they do the sturdy sense of social order.

No stooping but envied peasant women from Millet and Van Gogh appear in these Boston School paintings, and no mundane but admired Mary Cassatt madonnas either, but neither do many men. The Boston School artists seem to have been celebrating their own newly acquired freedom to salvage something from the imaginations they’d been accused of surrendering themselves so hysterically to at home, something of the tendency toward the dreamy and the impractical and the intuitive that had been the damned domain of the flaky female, and something of the love of sensual effect that, so they say in the history books, had given them the Eve-engendered reputation for evil-doing. They couldn’t help it that the freedom came first to them and only much later, if ever, to women of lesser means, whether of pallor or of color. What Virginia Woolf called a potential female artist’s need “to feed upon the lives of men and women” could at least get sated for a change.

Nor is that to say that all of the Boston School works served to embellish the class-conscious cliché. Anna Vaughn Hyatt’s vigorous sculpture of a jaguar (a la Delacroix), and her delicate sculpture of the mythical young goddess of the hunt Diana (looking lithe and lovely with bow and arrow); the plaster castings from Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller’s Emancipation (it’s in Harriet Tubman Square, by the way); and Margaret Foster Richardson’s decidedly unglamorous self-portrait, happily homely and irrepressibly inspired in her granny glasses and blue smock—all point the way out of this enclosed, gated-community sensibility so indulged in by the super-sensitive aesthetes of the day. It turns out that the immigrant communities of the West End and the North End, as well as those of the South End, were just around the corner from Beacon Hill and the Back Bay.

Polly (Ethel R.) Thayer was among those women artists of privilege in Boston lucky enough to be born toward the end of the Boston School period. (Suffrage had happened. Sexual mores had loosened. Amelia Earhart was in flight.) Thayer’s voluminous and luminous nude, entitled Circles, hangs in the Boston School section, showing a cream-colored female form from behind in a classic model’s pose, turning to her right, her Rubenesque hips and long back and fine neck leading the venerable and vulnerable onlooker to wonder how beautiful her turned-away face must be.

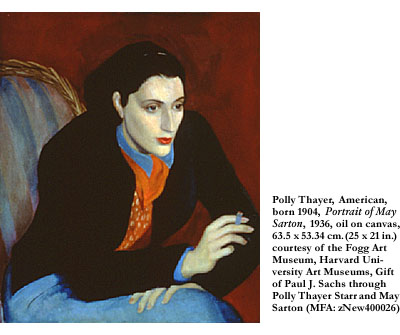

But another great Thayer painting, less Ingre and more angst, full of what a caption calls “flattened planes of pure color” typical of the times, hangs in the Modern Women Artists room. That’s the small third gallery in the show, almost easy to miss or underestimate because of its shadowy lighting and dark walls, but as wonderful to find as a secret chapel in a huge cathedral. This room’s the climax of the show, with enough pulsating and vibrant work in it to bring to happy resolution all the ambivalent suspicions one may have harbored about the first 50 of the 70 total years covered in the exhibit. Suddenly, embarrassing the viewer who scoffed at the earlier depictions of bourgeois comfort, these bold and brazen works done between the world wars remind the dismissing one that the good modern stuff by women couldn’t have been made without the rigorous practice of the previous eras. These modern pieces transcend the traditional and stereotypical female considerations of social status and decoration represented in the Boston School, synthesizing the decorative impulsive of that School with the reformative impulsive of the Arts and Crafts period. As if to suggest that the women artists of Boston broke their mind-forged manacles, now the pink-and-purple mist emitted by fresh-cut flowers and ivy-covered windows has been dispersed. Less dressed up and more stripped down, some of the artists in this period are not even from traditions of privilege, and a few of them are women of color. When suffrage is granted, it’s as if colors come into focus for the first time. Veils of tears part from women’s faces. The air of sanctified high taste clears, and with it the aroma of fresh-cut flowers.

It’s Thayer’s Portrait of May Sarton, a depiction of the late poet in the prime of her life, on loan from the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University, that presides most forcefully in this room. Sarton, a heroine of liberal-left lesbian activists in recent years, leans forward, dark hair held back with a band, smoking in her bold green jacket, orange sweater showing underneath, turquoise cuffs and pants contrasted dramatically against a crimson background. The face of the poet who wrote about the solitary life of the writer, about a woman’s love of women, is angular, pellucid, handsome, engaged, determined, intrigued, and receptive. Though an icon of modernism, Sarton wrote in traditional (some would say stiff) verse forms. Here, she seems to be leaning into the darkened room of the Modern collection to hear what the others have to say.

She’s hearing what the thoughtful-looking black man in Lois M. Jones’ portrait is saying—something to do with the Emancipation casts in the other room, maybe. She hears the harried-looking woman in Margarett Sargent’s Beyond Good and Evil (Self Portrait), in her variegated summer dress, become the medium of all suggestive distortion, squeezed into the long and narrow frame with allusively symbolic dove, cat, and dog images, her face indicative of the damaged goods within. The liberated, intellectual, cigarette-smoking sage, Sarton hears the Striding Amazon sculpture by Katharine Lane (later Weems) announce her bronze athletic presence nakedly and proudly to the world, flexing her posture without a care for the censorious response, or even the approving applause, of the men who rule the worlds of art and commerce. Sarton even seems to be listening for messages from Thayer’s own self in the nearby Self Portrait: The Algerian Tunic—and the self-portrayed Thayer in turn seems to be turning her head to hear better herself, her short red haircut, her lovely pale limbs, her strong left hand grasping a long assertive paintbrush in a keen state of readiness to depict her own pose, the bowl of fruit behind her ready for the still life, her purplish kimono open to the breastbone to reveal a long cylindrical neck of admirable tension and strength. All the way back through the large rooms devoted to the Boston School, back into the smaller room of Arts and Crafts, Sarton’s hearing reaches, till finally she can identify that low sound, like surf rolling pebbles on Singing Beach up the coast in Marblehead—she hears the snoring of the servant woman in the Anne Whitney sculpture. And she knows that Leif Eriksson, too, discovered America.