In the quiet woods of Maine, it is easy to lose yourself among the trees. The idyllic natural backdrop of unmarred light and darkness is a reminder of why so many people dream of coming here to get away from common cares. Yet here also stands well-known Colby College, with its Georgian-style brick architecture, historic hallways, stone solidity, and a few old memories. A good deal of them are housed in the Colby College Museum of Art, and as of July 2013, within a modern glass wing to the museum known as the Alfond-Lunder Family Pavilion, where a varied, exquisite art collection has been recently acquired through the family’s great generosity. The Lunder Collection includes more than 500 impressive objects of mostly American art, valued at over one hundred million dollars. The pavilion was planned in the years following 2007, when the intended gift of artworks was first announced by longtime benefactors of the college Peter and Paula Lunder, and the completed building unveiled on opening day is a masterpiece in itself. The inaugural exhibition, The Lunder Collection: A Gift of Art to Colby College presents more than 280 artworks, featuring the collection’s strengths in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century American and contemporary art, and will remain on view through June 8th, 2014.

Looking up at the pavilion on a bright summer’s day, you can instantly appreciate its delicate mirror-like quality—it looks as though the whole thing is fading into the sky, giving nature back unto itself. Designed to reflect its surroundings—trees, sky, buildings—it also shows glimpses of what is inside, bringing interior and exterior together into a continual whole. Within, there lives an entire cycle of Western art, interspersed with an excellent collection of Eastern pieces, charmingly arranged upon the spare, large walls and pale lacquered wooden floors. Somehow it is like a miniature Metropolitan Museum of Art, but more personal. The large Sol LeWitt installation on the pavilion’s east wall is splendidly dazzling, and a wonderful welcome to the museum when seen behind the glass façade. The artwork is called Wall Drawing #559 and is on long-term loan from the estate of Sol LeWitt. The title might not explain much, but the work speaks for itself. A three-color rainbow radiates from the upper right-hand corner of the building. The yellow, red, and blue rings echo down diagonally, alternating with one another and perhaps representing the way the sun’s rays enter the confines of the glass, a continuation of nature’s light in artistic form. Much of the museum is reminiscent of this idea—setting and history crystallize into a moving artistic moment.

It takes a lot to make a place of objects so vivid while leaving room for the resonant nostalgia of history. Certainly, the Lunders’ benevolence has given people a new treasure to discover, and the museum is open to everyone, free of charge. The building itself, designed by Los Angeles-based Frederick Fisher and Partners Architects, reflects a great deal of mind and matter. As Fisher explains, “This new pavilion is conceived as a glass prism that will reflect its natural and architectural context in continuously changing images. The reflecting nature of the glass expresses the theme that art provides the opportunity to reflect on life. This was central to the museum’s position as a beacon of creativity and innovation on campus.” Sharon Corwin, the Carolyn Muzzy Director and Chief Curator of the museum, believes that this harmonious combination of style and subject has the potential to make the place a standout among New England museums, and as many admirers have agreed, in the country and world as well. When curious people asked Peter Lunder (class of ’56) “Why Colby?”—he responded that here, the family could be sure the art would always be shown, mindful of the reality that many of the larger established museums have to cycle parts of their collections in and out of storage due to capacity. The new pavilion wing represents the culmination of many years spent by the Lunders fondly and reverently selecting the best and sometimes most unusual pieces. The museum will now comprise four wings totaling 38,000 square feet of exhibition space, as well as space for the college art department and museum administration.

In terms of quickly noticeable concentrations, the collection is known for having some of the great Winslow Homer and James McNeill Whistler works, which shows that not for nothing do some people consider this museum a great harbor of New England art. The American Impressionists and Romantics have always had a special power over me, which I felt again when, walking through the awning of a sunlit gallery, I was instantly drawn to George Inness’ painting Spirit of Autumn (1891). Something about it broke down my barriers, and for the rest of the day I walked around more fluidly, more engaged, and less afraid, somehow feeling at home. Maybe it was because I always felt my feet carry me to works of art that made me want to live in them, but this tranquil scene, of a quiet, lonely bit of wooded countryside, captures the sorrow inherent in transition, showing the fade and mute on a bright reflection in still water. I had not encountered many Impressionist pieces that carry a shadowy undertone.

But seeing in a new way what you thought you already appreciated long ago is another characteristic of this museum’s experience. When I turned around and saw a marble statue of a young woman, I walked up to her and wondered what her story was. She looked so young but seemed so lonely. It was of Undine, a tragic figure whose tale has haunted artists since the 1500s. She was a bewitchingly beautiful water nymph facing a strangely familiar choice—to allow herself to fall in love with a mortal man, only to lose her immortality (and then also her nerve, when the mortal man she loved eventually cheated on her), or to live forever immortal, but without a soul. Though people have experienced her story over and over for many years through the music of artists such as Debussy or Tchaikovsky, or through paintings, poems, and novels, she remains an enigma as she stands there on a narrow column pedestal, a statue sculpted by a relatively unknown artist named Joseph Mozier in 1866. I still do not know why she holds a veil over her face—maybe so that nobody falls in love with her, for after all her expression and posture is a combination of sad and wistful, innocent and a little bit shy. Always yet unmarried, always a bit afraid, she will forever be surrounded by strangers stopping to look, like I have, at her hopeless situation. I hope our perception of her might give her a soul. I know it also reminds us of ours while giving us a moment of immortality.

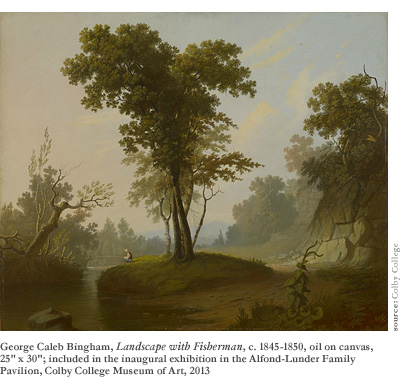

Moving onward, I saw George Caleb Bingham’s Landscape with Fisherman (c. 1845-50), and though the fisherman looks lonely as he sits absorbed in his small daily task, he is actually being overlooked by the tree, and the tree by the cliff. Oblivious to them, he is overlooking the water. No one knows how much time has passed as he sits there in that quiet harmony. That was a bit how I felt looking at these particular artworks—like a character inside their world, given a chance to muse in solitude on the wing of a native environment where modernity and nature come together. Another pleasing work was gently impressionistic but tinged with a hint of gloom—John La Farge’s painting, Agathon to Erosanthe (Votive Wreath) (1861). Agathon was an angelic young Athenian tragic poet whose works have been lost, but through this devotional offering we can forever see the expression of his love. The timeless confusion of place and time, and the wreath being the only focus of the painting, makes it very endearing since we know that flowers are always on the verge of fading.

Along my walk upstairs, I then passed through the excellent section of ancient Asian art. Lit with a soft, sultry light, there are many unusual, delicate pieces, such as an exquisite blue and white fine-tooth comb, as well as larger works like scroll paintings and sculptures. Artifacts include a pagoda tile of earthenware with green glaze, made in China during the Northern Qi dynasty (550-577 C.E.) or Sui dynasty (581-618 C.E.). Like the aura of the museum itself, there is a lot of motion set in the stone, in the figure’s curvature and animation.

Coming back downstairs, I traveled a few millennia forward into the section of modern art, where I was struck by the poignant irony of The Human Spill (2008), by Fred Wilson. I found myself hovering over a globe tilted on a diagonal silver stand, painted with shiny black/brown paint-like oil and crying shimmering glass spangles. The world looks like a charming, jaded object from a bygone and decadent era, and the spangles like flowers, seaweed, or most certainly teardrops—conflating scales of distance and measure. The ambiguity of scale indicates a possible analogy of the world as some forgotten art installation—a thing used, elevated, and forgotten. Not a bit of the little painted globe is spared from natural human complicity in its suffering.

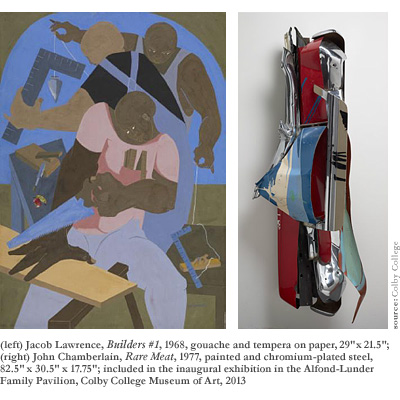

Another work that instantly affected me in this section was Jacob Lawrence’s painting Builders #1 (1968). Viewers are probably first struck by the fear that the main figure is cutting off his own hand with a saw. If you look closely, however, you see that it could just be an illusion as a result of foreshortening. The hand the character has placed on the wood he is cutting is disproportionately large yet chicken-foot-looking. Its claw-like appearance makes him seem desperate, reducing his feelings to elemental pain, and the surrounding cacophony of right angles set in dissonant relation to one another only accentuates the routine quality of it, as though while working at these physically unforgiving jobs, these men are continually lopping off pieces of themselves.

But not far away stands Claes Oldenburg’s Model for Clothespin (1974). At first you might just glance at it, perhaps once more bemused by the inscrutable oddness of modern art, and almost begin to move on, when, if you are lucky, you will suddenly notice that the shadow it casts on the floor is of two figures embracing and about to kiss! Nowhere does it indicate that was the artist’s intent, but you feel as if you have suddenly made a wonderful discovery, and not sure if it is a coincidence, you walk on. Later, you might find out that many people agree the clothespin does look like two lovers. But the point is that all the works in the museum leave you feeling this quaint sense of recognition and uniqueness as well as a luminous mystery. It is amazing how much vitality the place has, while being so serene. I experienced a little of the passion Peter and Paula Lunder must have felt when collecting their artworks, each one after the other. Thanks to them, we have been given a chance to fill gaps in our knowledge, stimulate our longing to dream, and help us look upon life itself as art, as the most genuine and glorious creation.