“All this academic art is far worse than the trade in sham antique furniture; for the man who sells me an oaken chest which he swears was made in the XIII Century, though as a matter of fact he made it himself only yesterday, at least does not pretend that there are any modern ideas in it; whereas your academic copier of fossils offers them to you as the latest outpouring of human spirit, and, worst of all, kidnaps young people as pupils and persuades them that his limitations are rules, his observances dexterities, his timidities good taste, and his emptinesses purities.” —George Bernard Shaw, from Man and Superman

How does the above passage relate to suburban Boston? These places on the fringe of what urbanophiles consider “cultured” host one of the most vibrant collections of creative self-expression in the Metropolitan area. Within neighborhoods like Somerville, Medford, Malden, and Revere, bizarre installations of tchotchkes in houses, yards, and on vehicles speak to another avenue of the latest outpouring of the human spirit Shaw refers to. They represent themselves on their own terms, incorporating objects that if standing alone would not have the same visual impact.

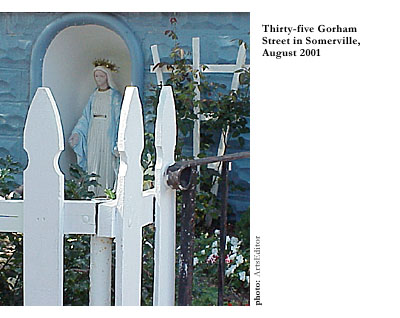

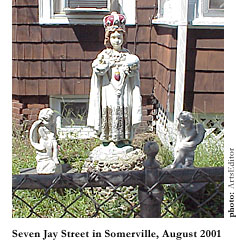

Many blanket definitions for such creations, like “Kitsch,” “Outsider Art,” and “Art Brut,” betray lofty and cloistered attitudes of those whose timidities are considered good taste. More accurate terms to use might be “lawn art” or “visionary installation.” The majority of the pieces in the Boston area are visionary in nature. A visionary piece is usually one by a self-taught artist whose creations hold echoes of the mystical planes they inhabit. These pieces create worlds around family history, spiritual outlook, and individual expression through ready-made elements, and often the materials are non-conventional. The saints represented in this area are primarily the Virgin Mary and St. Anthony. Both figure heavily in Italian American lore, and people of that descent are the ones that tend to host such installations. The American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore hosts a variety of exciting exhibits, and is a great place to explore Visionary Art further.

In his essay Annunciation of the New Mysticism: Dutch Symbolism and Early Abstraction, Carl Blotkamp cites a lecture given by Frank Stella in the early ’80s where the artist asserted that “the theoretical underpinnings of Theosophy and anti-materialism have done abstract painting a disservice.” Blotkamp then highlights that there is a certain skepticism regarding the occult rather common among today’s intellectuals. The pop-socialist attitudes Blotkamp pinpoints inform those notions, asserting that because of the “religious” infusion present in these works, their validity is questioned. Add to the mix that they are western and Catholic in origin, and one can declare open season on their “taste.” Separation between “high” and “low” art is often a distinction made by those threatened by alternatives to prescribed thought and manners of expression.

After Dada, where Duchamp illustrated the power of the artist’s transformative touch with the ready-made, new doors opened when considering what makes “art.” Artists like Ana Mendieta and Richard Long worked within a landscape—using found, organic objects to create presence outside of the gallery setting. Their efforts to use unusual material emphasized their sensitivities to the idiosyncrasies of the creative process. Expression flows from many sources, and manifests itself in places unexpected. Joy comes in the discovery of the care that one took to create in a place that might not summon sensations of beauty or revelation at first glance, or that might not be considered as anything but a green strip outside a house. The process taken to transform a space is just as powerful as the finished piece. In many ways these installations represent time and connections to inner spaces, spaces that need to be defined as sacred.

After Dada, where Duchamp illustrated the power of the artist’s transformative touch with the ready-made, new doors opened when considering what makes “art.” Artists like Ana Mendieta and Richard Long worked within a landscape—using found, organic objects to create presence outside of the gallery setting. Their efforts to use unusual material emphasized their sensitivities to the idiosyncrasies of the creative process. Expression flows from many sources, and manifests itself in places unexpected. Joy comes in the discovery of the care that one took to create in a place that might not summon sensations of beauty or revelation at first glance, or that might not be considered as anything but a green strip outside a house. The process taken to transform a space is just as powerful as the finished piece. In many ways these installations represent time and connections to inner spaces, spaces that need to be defined as sacred.

Looking at the creations in people’s lawns, one finds a peculiar and engaging confluence of the aforementioned currents. Most of the objects are pre-fabricated. Most of the objects are created en mass. Most of the objects follow the function for which they were created—i.e. lawn decoration. Not much imagination? On the contrary—the exciting moments evolve with the choices the artists make when combining the objects with each other and with the landscape. These decisions highlight outlooks and personalities as well as the sanctity of each space. Including saints with gnomes and mermaids illustrates searchings for a connection to social and community identity, and also those more personal searchings for inner voice.

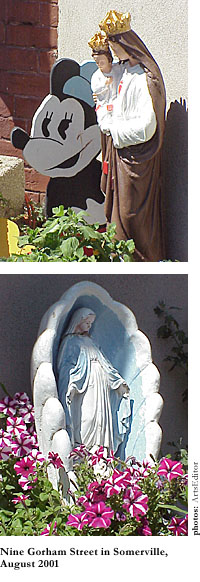

Number nine Gorham Street in Somerville hosts a fantastic smorgasbord of objects in an engaging arrangement. Passing the space, the viewer immediately sees a fabulous collection of seemingly random items. Skunks, wooden cutouts of brightly painted boys and girls, geese, a mermaid, and a Virgin Mary on the half-shell populate a roughly 10 x 10 foot square of yard. Sadly, the mermaid fountain is not running. How these pieces relate to each other is baffling at first glance, but there is something potent in the volume of objects together in such a small area. This intensity develops a more cohesive picture after the initial jarring visual introduction. In another corner of the yard, the artist has positioned Minnie Mouse, the Easter Bunny, and a Mary with child. Here, the boundaries of “taste” and sanctity come into question—what do a popular commercial figure and the mother of Christ have to do with one another, and where do the geese and skunks fit into the equation?

Number nine Gorham Street in Somerville hosts a fantastic smorgasbord of objects in an engaging arrangement. Passing the space, the viewer immediately sees a fabulous collection of seemingly random items. Skunks, wooden cutouts of brightly painted boys and girls, geese, a mermaid, and a Virgin Mary on the half-shell populate a roughly 10 x 10 foot square of yard. Sadly, the mermaid fountain is not running. How these pieces relate to each other is baffling at first glance, but there is something potent in the volume of objects together in such a small area. This intensity develops a more cohesive picture after the initial jarring visual introduction. In another corner of the yard, the artist has positioned Minnie Mouse, the Easter Bunny, and a Mary with child. Here, the boundaries of “taste” and sanctity come into question—what do a popular commercial figure and the mother of Christ have to do with one another, and where do the geese and skunks fit into the equation?

Rebirth and rejuvenation—the mélange speaks of the hope inherent in spring as representative of youth and the future. There are no plaster cast Josephs or old ladies. All elements within the installation highlight the faith in the future—offspring—as seen in the baby skunks and the Christ child, rebirth and the coming of pure love.

In Greek mythology, Aphrodite, the goddess of love, arrived on the island of Cyprus on a shell in a bed of foam. Coincidentally, or not coincidentally, many of the Marys in this area reside in shell grottoes, or even in bathtubs. This arrangement might allude to a loose connection to Aphrodite. Mary’s status as the progenitor of pure love reflects the status of Aphrodite as the progenitor of Eros, which is the beginning of pure love. Both of these births were miracles because of their being devoid of typical human means of conception. Mary and Aphrodite represent idealized forms of womanhood, and in their respective states bore sons that would bring love into the world. Although their representations might be at odds with each other—the physicality of Eros vs. the spirituality of Christ—the tension created represents a loaded testimony of faith systems in a consumer-dominated culture, and how the lines between spirituality and purchasing power blur.

The most moving moment in the piece on Gorham Street is the interaction between the Mary statue, Minnie Mouse, and the Easter Bunny, which holds a “Welcome” sign. The union of such opposites, like a koan, forces the mind to make associations that might have been lost had there not been a striking contrast of pieces at odds with their surroundings. After the initial humor, there is something disturbing about the tenderness of the mother and child next to the popular agent that arrives after the child’s future physical self has been sacrificed. Making that moment almost Vaudevillian is Minnie Mouse, whose permanent smile seems to laugh at the horrible paradox behind her.

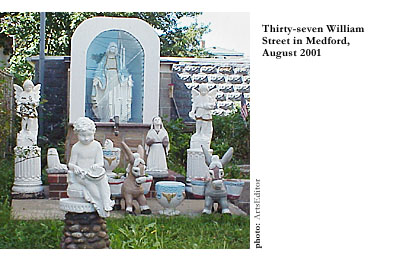

Thirty-seven William Street, off Broadway in Medford, is the site of a significant grouping of statues that is more outwardly pious in its tone than Gorham Street. An encased Mary looks out over a series of plaster cast cherubs, donkeys, urns, and searching figures. Her hands outstretched in a receptive gesture, she beckons the viewer into the world to see the figures assembled at her feet, with her cast-down eyes and blue robe that conjures images of the constancy of the ocean or the sky.

Her dominion resides on a concrete slab. All of her subjects face outward as if to greet the passerby. The installation is lovingly cared for, and there is a certain presence to the piece that at once embraces the viewer with its solemnity. The other two Mary figures, outside of the protective glass, have suffered the wear of outdoor exposure. One’s arms are gone, the other is split in half. That they are still there represents the poetry of the installation. The top half of one Mary resides in an urn, and it appears that she prays to her lower half. The other looks to the heavens with a beseeching gaze and stumps where arms once were outspread, in a gesture that can never be made fully. These damaged statues, repainted and cleaned, offer glimpses at redemption and the care that humans offer each other in light of their weaknesses and frailties. The humanity of these pre-made objects, accumulated through their experiences, has transformed them into more real entities, which correlates to the story line of the Velveteen Rabbit, where a stuffed animal becomes real through the affection of a child. There also appears to be an aura of redemption coming from Mary, as a giver of grace from her clean tabernacle on high.

The donkeys also work into the metaphor of the struggles of earthly life. They carry urns, but no flowers or plants grow from these vessels. They are empty, carried on the backs of these animals for eternity—or until they break off. Their emptiness represents toil without reward. Like their broken sisters, these animals look for fulfillment where it non-visibly exists. Faith and hope are the currency that carries these animals forward and connects them to the animals in the other installation on Gorham Street. The urns have the potential to be filled, fulfilling their function and utility.

As in the installation on Gorham Street, there are only statues of the Virgin, animals, and cherubim. It strikes an unbalanced note without a more masculine presence; if there was only grace in the world, how could there be the chance for redemption? This installation works as the best ones do—as a world that the artist creates, lacking only the dimension that each viewer brings to complete the harmony equation. The viewer as the variable forces the artist to almost bring the project to wholeness, yet maintain the distance to lure the passerby in to complete the picture.

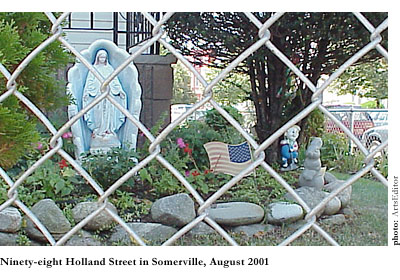

Another installation in Somerville, ninety-eight Holland Street has all the typical elements—the Virgin on the half-shell, bunnies, geese, as well as strange plastic creatures dwelling in the artfully manicured conifer bush. Themes of renewal and hope run through the piece with the bunnies and the grace of the Virgin’s gesture. The element that sets it apart is the plastic American flag. It stands before Mary almost as an afterthought. Plastic is the ideal choice for its composition as a flag waving in the breeze—permanently in motion, but static—unlike an often-limp cloth banner. More than anything else, it screams “AMERICA!”

Musician and visual artist David Byrne said in an interview about rock and roll that “the beauty of this ‘American’ aesthetic is that it belongs to anyone who claims it…who grooves on it…who sees the deep Zen poetry in James Brown’s lyrics, in a jukebox, a suburban split-level, a wild hairdo, who sees the hope for the future implicit in the shape of an electric guitar…here it was…do it yourself art/poetry/sex/life/bullshit that anyone could make and possibly reach a sizeable audience without compromise.” Those words ring true for lawn art also. The beauty of this country is paradox, tensions of objects juxtaposed but comfortable with their spaces.

Anyone could have taken these objects and put one or two on the lawn. The considerations and processes that these people assumed to assemble their installations and the care that they’ve taken to maintain them indicates a respect to their creative muses. As manifestations of personal expression, these installations highlight cultural backgrounds, philosophies, and outlooks that lie within each creator. Examining the contents of the yards reveals intersections of social currents like commercialism and spirituality. Seeing these installations as more than lawn ornaments imbues the neighborhoods with richer personality, bringing identities to the surface and sparking conversation and exchange.

Beyond these immediate rewards for an open approach to non-conventional art outside of a gallery or museum, there lies a deeper gift—heightened awareness of the rich diversity of human expression. To see the harmonies and beauties in this work, cultural programming must be left at the door and a more sensual approach taken. These pieces define time on their own terms. Learning from these fixtures offers a liberation from stagnant thought and a chance to glimpse the startling contrast of an electric yellow duck next to a solemn blue and white Mary.