Imagine a lush, green landscape filled with bountiful fields of nurturing earth; life-giving, flowing waters; sheltering trees; and a sky wide enough for the grace, guidance and guard of the divine to shine through unceasingly. Imagine then also a society which strives to maintain the purity of that land as equally as it strives to maintain the purity of thought among its personage, a focused idealism that is at the very center of the concept of utopian community and is, ultimately, the unattainable reality for a small group of such idealists settled near the town of Harvard in the mid-Nineteenth Century.

Such is the setting that Vasiliki Katsarou visits in her short film, Fruitlands 1843. The 35-minute film, which was shown recently at the Harvard Film Archive as part of the University’s “Arts First” Weekend, is a mediation of sorts, in that the narrative takes a more impressionistic approach to the story of this utopian commune. As Fruitlands 1843 begins, a voiced-over narration introduces us to the place and its inhabitants through a letter written by leader Stephen Alcott. As Alcott’s words invite their desired recipient to join in this place of “harmony and fellowship,” so too are we invited as viewers into this world. To be sure, as the narration falls away and the camera lingers in a way linked less with traditional storytelling and more with natural sensation, the remainder of the film is designed to allow us the privilege of being right there, then, and with those people. The feel of Fruitlands 1843 is more dreamlike than linear, with scenes that do not necessarily play in chronological order but are unraveled in a more thematic order. And despite its dreamlike quality, the film could not feel more real for the viewer. While there is no heavy-handed or explicit discussion of the history of Fruitlands, there is attention to the most minute detail of each scene, giving a greater weight to our sense of what it is like to be a part of this place. Several outstanding examples of Katsarou’s consideration to detail would be easy to overlook by critics unfamiliar with the challenges of showing a story, rather than telling one. And Katsarou does just that—her deftness in balancing the historical symbolism with the craft of filmmaking is worth a close look.

An example of such careful and meticulous filmmaking centers on one of the first scenes in the film. It is a scene where two men—presumably the leaders of the community—bathe in cold water at the onset of the day. In reading about the community of Fruitlands, we learn that bathing in cold water was protocol for the dwellers. In her research, Katsarou was obviously familiar with this detail, chose to incorporate it, and through its filming, reveals what lies at the core of the two leaders of the community. As the character of Alcott pours water over his head, he is smiling; he appreciates the beauty of the day. We, as viewers, appreciate the day with him, as a wonderful point-of-view shot reveals pristine wilderness, as birds provide a melodic chorus in the background. As the second Fruitlands leader pours water over his head, he does not look at his surroundings. He is not as moved by the forest and trees as Alcott. With the first viewing, this scene might not have any obvious significance for viewers. It is one, however, that warrants subsequent viewings, for it reveals much about Katsarou’s depiction of Alcott’s ideology. From this scene, we see that there is a true and spirited love of Alcott’s for the land on which his community was built. Though Fruitlands was short-lived, we see that Alcott’s intentions were to experience a sense of community in keeping with true transcendentalist principals. For Alcott, “harmony and fellowship” began with a deep and spiritual appreciation for the natural world.

It is in this way that the film has resonance for the viewer, a resonance that Katsarou herself felt visiting the land where the true story took place, and in the study of those who lived there. Her chief motivation in making the film, as related to the Harvard Film Archive’s audience during a question-and-answer session following the May 6th screening, was to impart those things about the place and the story that had stayed with her: the beauty of the area and the conflict in the belief system the settlers of Fruitlands had set for themselves. The geography itself would be reason enough. Katsarou stated that being in that place truly was transcendental, and could perfectly relate to the original group’s inspiration for choosing that particular place for their utopian society. In truth, the scenes of nature in this film could not be more beautiful. The cinematography captures perfectly a wonderment and respect for the land. Production was abetted by a May shooting schedule that took place in the same season as the original commune’s joyful beginnings. It’s hard not to be awestruck by Katsarou’s graceful approach to the original grounds of Fruitlands.

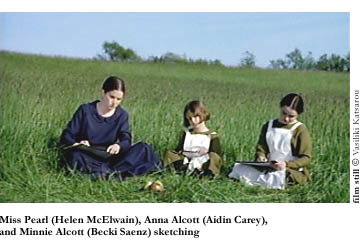

Another reason for choosing this subject was, as Katsarou describes it, “the theme of difficulty living up to one’s ideals and the difficulty of reconciling the demands of the spiritual world and the material world.” This concept she revealed to be “what this film is about, ultimately.” Katsarou lets us glimpse this struggle in every member of the Fruitlands community. There is a general desire to make the community work, to live out the ideals of virtue, hope and respect. We are, however, constantly reminded that humans are not infallible, nor can one be entirely devoted to one’s pursuit of ideals. This is exemplified in a pivotal scene in the film, one that we believe captures both the restlessness of human nature, and the emergence of personality. We are first introduced to the Alcott children as they draw a still life under the guidance of their teacher, Miss Pearl. There is a sense that we, as viewers, are interrupting something that is initially very personal and ethereal. The camera holds on these three figures, as they sit in a field of tall grass (here, they are nearly dwarfed by the landscape) and draw a still life of fruit. We watch this scene for several moments, as the camera provides us with an unflinching gaze on the three figures. It would seem almost unreal, in that the stillness of the three figures is so unlike most characters onscreen in recent films. They, unlike many modern characters, are not in furious motion; they are simply drawing and we must take it all in. This scene shifts as personalities emerge to the surface. The younger of the two children, Minnie, jostles her sister’s arm, causing a shift in our focus. As this shift occurs, perhaps one begins to understand the significance of this scene. On this point, Katsarou states, “In every part of this film, some character is doing something, however trivial, significant, unconscious or deliberate, to undermine the community. It is the same in this scene. Minnie undermines Anna and this is reflected in a purely visual way.” The balance of the situation—peaceful contemplation of the natural world (perhaps symbolized by the still life) is upset by the eventual emergence of an individual’s needs, wants, or even unconscious motion.

It’s a topic one would not expect covered or even attempted in one scene in a mere 35 minute film, and for this reason Katsarou said she has plans to possibly turn the Fruitlands story into a full-length feature. It’s one of many scripts she has in the works. It is admirable, however, that such a short film should contemplate such lofty themes, and certainly Fruitlands 1843 was not made with any hope of answering any questions, but rather in the hope of raising questions and opening up possibilities for intellectual consideration.

The film succeeds remarkably to that end, but what is more remarkable is that on another level the film can be simply enjoyed as a string of sensations with no pretense other than the enjoyment of the film-viewing process. In other words, it’s as rewarding to watch as it is to think about afterward, a rarity in reality-based or documentary style filmmaking. This is largely because of the scenery, the crisp beauty of the camerawork, and the evocative sounds in the film, which range from an eerie hum to the prettiness of the score by Richard Whalley.

For a film with little exposition, the characters seem very real. This may be attributable to the quality of the ensemble acting or to the richness of the personalities from which these characters are drawn. And frequent shifts between the characters come before we feel the comfortable scene closure expected in traditional cinema. This does much in serving to aid in our perception of those individuals as a society. But we find that ultimately the individuals that inhabit Fruitlands are just that—individuals. Its members, as portrayed in Katsarou’s film, seem unaware that the utopian ideal is a model only and not, itself, an achievable or livable thing without sacrifice and concession.

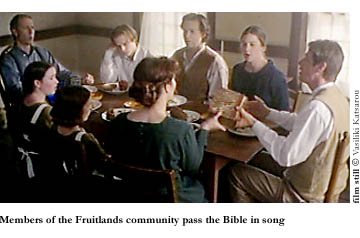

The dissolution of the society is echoed in an apparent dissolution of traditional narrative structure. For only 35 minutes of film, its structure is incredibly engineered. Through an increasing frequency of cuts and chronological inconsistencies, as well as the gradual disappearance of narration and eventually, made to fullest effect in the film’s final dinner scene where one by one the members leave the table, the disappearance of dialogue or communication of any sort, the sense of the failing commune is evoked.

And yet, is it really a failure? An ending which portrays the innocence of youth skipping through the forest is perhaps more symbolic of the future than anything else. Does that lead us down another path altogether, from where mistakes may be learned? These questions and more are evidence of Katsarou’s intention for the film to be open-ended and lending to interpretation. And this is a desirable result of Katsarou’s non-linear and symbolic storytelling. She writes, “I think Fruitlands 1843 rewards the viewer who is willing to peel away the surfaces and delve deeper.” Each viewer may take from it what he or she wishes, and in doing so, may be reminded that these events really did not take place that long ago. These are universal issues that are still struggled with, in various ways, in modern society.

Fruitlands 1843 will be shown at an encore screening at the Museum of Fine Arts this fall. Katsarou has also been invited to screen her film at the prestigious Anthology Film Archives in New York later this summer.