in·cu·bus (n.)

1. An evil spirit supposed to descend upon and have

sexual intercourse with women as they sleep.

2. A nightmare.

3. An oppressive or nightmarish burden.

Incubus is a chilling black and white American film from 1965 that tells a timeless tale of good vs. evil. It features as its star William Shatner, who was soon afterward to sign on with a television show called Star Trek. The film has remained somewhat of a footnote for many years, largely because it was taken out of distribution when two of the actors died within a year of the film’s release. Fearing a purported “curse” on the film, the director ordered all prints withdrawn, and Incubus subsequently remained “lost” for over 30 years. Until now, as they say. Incubus has been “found,” restored, and released on home video with English subtitles. Why the subtitles? Incubus also has the distinction of being the first and only feature film conceived and performed entirely in Esperanto, the artificial language created in 1887 with designs of becoming a universal tongue. Because it was out of circulation, the combined curiosities surrounding Incubus have long been only rumored, and only now with its belated release on VHS and DVD from Winstar Video can this most intriguing motion picture be truly appreciated.

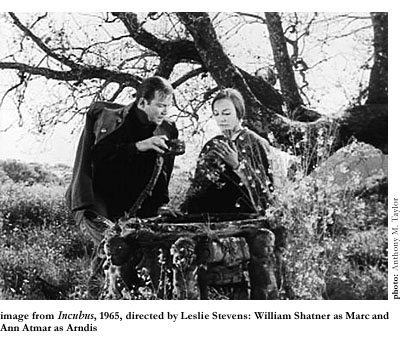

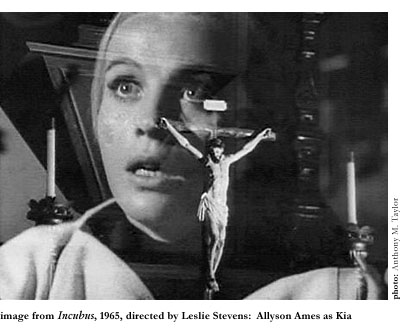

The story takes place in the fictional village of Nomen Tuum, which in Latin means “your name” (or “thy name” in the Lord’s Prayer, which is probably the point of reference for this allegorical and darkly religious film). In this strange place live succubi, beautiful young women in service of the dark side, whose role is to lure men to their fate in hell. The succubus Kia is tired of tempting only tainted souls, and decides one day to go after the soul of a pure and just man, Shatner’s Marc, but she inevitably finds herself falling in love with him against her will, an act which defiles her evil with good. This prompts Kia’s elder sister succubus to beckon the Incubus to bring revenge on Marc and his hapless sister, with whom he lives and cares for.

The story takes place in the fictional village of Nomen Tuum, which in Latin means “your name” (or “thy name” in the Lord’s Prayer, which is probably the point of reference for this allegorical and darkly religious film). In this strange place live succubi, beautiful young women in service of the dark side, whose role is to lure men to their fate in hell. The succubus Kia is tired of tempting only tainted souls, and decides one day to go after the soul of a pure and just man, Shatner’s Marc, but she inevitably finds herself falling in love with him against her will, an act which defiles her evil with good. This prompts Kia’s elder sister succubus to beckon the Incubus to bring revenge on Marc and his hapless sister, with whom he lives and cares for.

Esperanto, as Incubus‘ sole language, was by most accounts chosen to give the film an otherworldly and mythical tone. Due largely to its use of the language, Incubus feels foreign, and the mood and setting in general evoke Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal, though writer/director Leslie Stevens considered the film to be more in the style of Akira Kurosawa and other Japanese filmmakers of the time. Stevens created the popular Outer Limits sci-fi television series of the early 1960s, and brought to Incubus many of the talents (including Shatner) whom he’d met while working on that acclaimed show.

Shatner, a seasoned actor on Broadway, in films, and on television both in the U.S. and his native Canada, had proven his acting mettle in an incredible and overlooked performance in Roger Corman’s 1961 racial unrest picture The Intruder. Due to his TV work on The Twilight Zone and one memorable episode of Stevens’ Outer Limits, plus his role in Martin Ritt’s film The Outrage (a 1962 re-telling of Kurosawa’s Rashomon), Shatner was perfectly suited for the role in Incubus. Among the other talents who helped develop the unique atmosphere on this art-horror film are cinematographer Conrad Hall, who later won Academy Awards for his work on Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid in 1969 and American Beauty in 2000, and his accomplice, assistant cinematographer William A. Fraker. Dominic Frontiere contributed a bizarre musical score which combines strings, harp, vibraphone, and theremin to a haunting and unsettling effect. Another contributor whose distinctive style is present is Fred Phillips, the make-up artist who worked with Shatner again on Star Trek, where he created the pointy ears worn by Leonard Nimoy in the iconoclastic role of Mr. Spock.

On one of the DVD’s two audio commentaries (the other features producer Anthony M. Taylor and cinematographers Fraker and Hall), Shatner remembers the film’s ten days of shooting in the Big Sur region of California to be plagued by rain and mud. He also recounts the intense two-week Esperanto camp which all of the actors attended, and director Stevens’ exclusive use of Esperanto on the set (to the confusion of both cast and crew). Shatner’s commentary is perhaps gratefully sparse, but he does go so far as to claim that Gene Roddenberry originally desired Star Trek to be filmed in Esperanto, and also reveals a possible origin of the infamous curse on the film—perhaps administered by an angered hippie vagrant that wandered by during production. The alternate commentary and bonus interview conducted by a Leslie Stevens historian is slightly more illuminating, with insight into Stevens’ obsessively odd character. It is revealed, for instance, that for scenes filmed at a monastery, Stevens devised an entire alternate ‘stealth’ script, a fabricated educational documentary entitled “Religious Legends of Old Monterey,” to keep the Franciscan Order at ease during the shooting, a creative and original notion worthy of Esperanto’s founders.

No less creative is the groundbreaking camerawork by Fraker and Hall. Many of the shots are purposefully obstructed by trees, leaves, water, and blades of grass—part of the film’s fascination with the elements of nature—and others are taken through netting, framed by window panes, or shot from below, signifying the depths of the film’s ever-present evil.

Unlike the usual horror film, and more akin to the films of Bergman, Incubus is very poetic in its storytelling. The stylistic filmmaking relies heavily on symbolic conventions that bolster the struggle between good and evil. Apart from the contrasts made by body and soul (“Our bodies mean very little,” pleads Marc innocently to Kia, “unless we give our souls to love”), the greatest conflict in Incubus is the arrangement of light and dark. The first two thirds of the film take place during the daytime, with beautifully lit scenes that play with casting unique shadows. There is an excellent scene where the shadow caused by a solar eclipse is weighted with great symbolic quality, and Marc tells Kia how the direct light poses the danger of burning one’s eyes. At exactly 45 minutes into Incubus everything becomes black with the night, and remains so for the last half hour, where the standard convention of ‘day for night’ shots adds an extra sense of eeriness. “The darkness seems to soothe me,” speaks the character played by Ann Atmar (in Esperanto, remember), who is plagued with blindness through her own mistake of staring at the sun, and is then cruelly punished by being made mute and, ultimately, demonically raped.

That darkness later enveloped Atmar in real life when she became the first victim of the legendary Incubus curse. Just weeks after the film wrapped, the actress committed suicide. Atmar played the role of Marc’s sister and victim of the Incubus, whose violation of her character in the film (a precursor to a similar demonic act of sexual intercourse in Rosemary’s Baby) contrasts with the “holy rape” that Kia’s elder sister proclaims has been committed on the younger succubus by Marc’s love. It may be no coincidence that Rosemary’s Baby director Roman Polanski was in the audience at Incubus‘ film premiere, but could it be the curse which befell Sharon Tate, Polanski’s date that evening, who was murdered three years later by Charles Manson and his followers?

Milos Milos, the actor who portrayed the character of the evil incarnate Incubus, is also said to have befallen the curse. Shatner remembers Milos to be an unfriendly character on the set, who, when addressed as “Milos,” had cryptically warned the star to never refer to him only by his surname again. Milos, too, committed suicide not one year after the filming, but only after first murdering Mickey Rooney’s estranged wife, Barbara Thomason, did Milos turn the gun on himself. The Incubus is called in the film to literally rise from below the earth to commit vile acts, and the knowledge of Milos’ later acts only adds a greater chill to the scene where he emerges from the dirt and with a fearful, entranced gaze utters one word only: “Death.”

The Incubus curse is also said to have affected many other members of the cast and crew. The daughter of Eloise Hardt, the woman who portrayed the elder succubus, was kidnapped and murdered a few years after the film’s release. The music editor wound up in prison for grand larceny. Even director Stevens found bad luck—his film production company, Daystar, went bankrupt shortly after the film’s release, his marriage to actress Allyson Ames (the younger succubus) ended in divorce, and he died prematurely in 1998 of complications resultant from a blood clot in his heart. As the protagonist, Shatner remained largely unscathed, unless one counts the 1999 death of his third wife by drowning in the family pool.

As bizarre as most of these tales of the Incubus curse are, and as fascinating and mysterious in retrospect as the film’s story is, nothing could match the curse of the film itself, which over the years had literally disappeared—all extant copies of the film seemed to have vanished. Were the missing negatives another part of the curse? If so, then it seems this greatest curse of all ended in 1996, when producer Anthony M. Taylor found to his amazement that a print had been playing at the Cinémathèque Française in Paris and that, in fact, the film had remained a cult hit in France for many years. It was this lone print of the film that was eventually (after a surprising amount of legal wrangling and technical hurdles) loaned to the original producer for the purpose of restoration. Considering the French print’s years of abuse, it’s amazing how remarkably well the film has been cleaned up, despite the fact that the French subtitles were too costly to remove; black bars with the English subtitles had to be superimposed.

With such an amazing and often unbelievable backstory, it is easy to overlook what a stunning film came out of it. The proof is here now, finally available on home video for exploration by the curious (and the few willing to sit through a black and white, subtitled film). The universality of Esperanto seems now a perfect fit for this tale, which like the language has many roots but no specific grounding. The basic themes and timeless quality of the film have aided it during its absence from the cultural consciousness, and now that it has been found, Incubus is assured to retain its particular mystique for years to come.