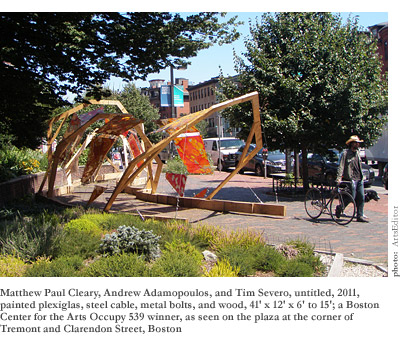

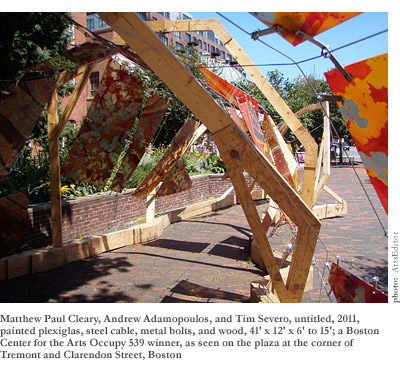

Coming upon the corner of Tremont and Clarendon Street, the commuter, tourist, and wanderer alike find themselves in the midst of a presentation. The modest yet spacious sidewalk in front of the Boston Center for the Arts opens up to a refreshing little garden, contained by a low wall street-side, and an iron fence on the other. The receding curb provides entranceway to the BCA’s Mills Gallery, Cyclorama, and Calderwood Pavilion, as well as The Beehive restaurant. City planners, it seems, meant this corner to invite pause.

Passers-by have all the more reason to linger now with the BCA’s Occupy 539 program, currently in its second year, which hosts public art exhibitions outside the building. Artists submit proposals for how they would “occupy” the space, and two winners are selected annually for a stipend of $1,500 each to produce their artwork. This year’s winners are Philippe Lejeune, a Boston-based artist focused on public performance, and a group of three—artist Matthew Paul Cleary and architecture students Andrew Adamopoulos and Tim Severo. Both artworks remain on view through October 23rd.

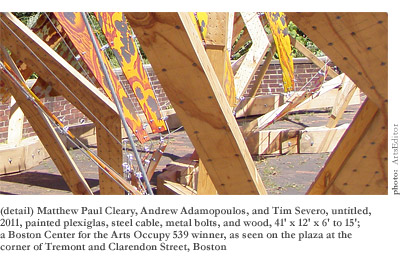

The group of three’s untitled collaborative piece is a 500-square-foot walkthrough installation consisting of painted translucent panels by Cleary attached to a wood-and-steel-cable frame. Built to sit close to the garden wall, the structure invites pedestrians to enter at either end of the piece, walking along 40 feet of winding passageway as the space constricts and expands angularly around them. The wooden frame of five tilted arches provides a skeleton from which issue the cables, securing in place the polygonal Plexiglas pieces, painted in warm, sunlit tones.

The structure overall has a rather rough feel, as the unfinished wood, pencil ticks, and other measurement marks remain unerased, apparent to the viewer. Russell LaMontagne of LaMontagne Gallery in South Boston, which represents Cleary, commented favorably on the “construction site” look of the piece, suggesting that for preservation and reinstallation purposes the wood might eventually be replaced by rusted metal bars or beams in keeping with that notion. Having interviewed Cleary and seen some of his other work in the past, I found this aesthetic of “roughness” a departure from his usual style, but appreciated its experimental quality. Curious, I spoke to Cleary, Adamopoulos, Severo and their mutual friend, artist Andy Young, at the BCA reception on July twenty-ninth and later again over the phone. They all had different stories to tell about their backgrounds and interests, and thoughts on how their distinct perspectives fed into the realization of the piece.

Cleary’s paintings are remarkably complex—active, expressionistic workings and re-workings of the acrylic resins and polymers that are his primary medium. One recalls the famous video of Jackson Pollock dribbling paint on a sheet of glass outside his East Hampton studio, as the camera records from the opposite side (Hans Namuth, 1951). The legacy of the action painter is further confronted in Cleary’s work, however, by his conceptual preoccupation with science and spirituality.

On the heels of the Dale Chihuly exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston that ended in early August, evocations of the natural world in Cleary’s artwork are all the more undeniable. Walking through the BCA piece recalls a stroll through a garden—more specifically, perhaps, a stroll through the perfectly-manicured Tuileries in Paris, themselves an enjoyment of nature as much as a celebration of man’s control over it. Cleary’s work embraces physics—the flow of paint with gravity, the varied viscosities and rates of evaporation of different materials all figure into the conceptual reiteration he enacts in creating his artworks. He works in concert with the elements he chooses, using his knowledge of their natural properties to manipulate them to desired effect.

W. B. Yeats said that “out of the quarrel with others we make rhetoric; out of the quarrel with ourselves we make poetry.” Art can be the arena in which paradoxes are explored and renegotiated, and within his art Cleary sometimes draws upon his Catholic upbringing to flesh out his personal take on the relationship between “the elements”—be they god or nature—and man. Every artist develops a relationship with his medium, but for Cleary this push and pull speaks directly to a “balance between chance and intent,” which “references spiritual structures of thinking.”

Cleary has in at least one instance explicitly included a subverted image of Jesus Christ in his previous work, and his choice of a straightedge to ply the paint in this most recent piece introduces a “man-made” aesthetic heretofore unseen in his paintings. I was able to see the piece entitled Crucifixion, which won Cleary the Traveling Scholars Award from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, while it was on view in the museum in the spring of 2009. A silhouette of Christ, taken from Matthias Grunewald’s 16th Century The Crucifixion, hangs in the center with six seven-foot-tall Plexiglas paintings mounted on rectangular lightboxes on either side. There, Cleary’s work resembles the view through a microscope—a sea of blood cells, dyed pink.

His continued emphasis on rational methods of exploration—as opposed to the divine—has led him to this year’s fitting collaboration with two students working on their undergraduate degrees at the Boston Architectural College. Andrew Adamopoulos and Tim Severo had learned to work together well over the course of several projects at the BAC, and had been working closely on the plans for a house in Sainte Catherine de Hatley, Canada, when Cleary approached Adamopoulos about submitting a proposal to the Occupy 539 program. The two had met at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, where Cleary was in the Post-Baccalaureate Certificate program, and Adamopoulos had spent a year trying art school on for size. While their personal preferences had since led them in opposite directions, their Occupy 539 submission allowed them a chance to bring what they had learned from their distinct educations to the same table.

An admirer of European Medieval and Renaissance churches, Cleary had been searching for a chance to bring his artwork into a more architectural context, and was eager to test the limits of painting as a two-dimensional experience. Having done installation work before, the Occupy 539 program was a chance to create a free-standing structure that featured his artwork. Adamopoulos, having spent high school at The Putney School in Vermont, had experience in fine artwork from stonemasonry to blacksmithing, weaving, kinetic sculpture, woodworking, drawing, and printmaking. Severo, on the other hand, had transferred into the BAC from studying mechanical engineering at the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado, compelled by philanthropic challenges like developing simple, well-designed refugee housing. His emphasis on social contribution provided another dimension of imagination and structural expertise for the group to draw upon throughout the project’s development.

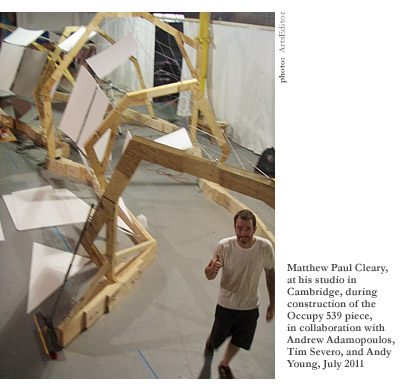

Cleary, Adamopoulos, and Severo spent a week on their proposal before submission, and two weeks later were informed that they had been chosen as winners. Now came the hard part—making the project come to life despite time and budgetary constraints. The structure required an estimated 500-600 feet of lumber, 250 square feet of Plexiglas, and 600 feet of steel cable, excluding the metal bolts and bars used as connecting joints. The first two weeks were spent refining their plan, after which the trio set to work on construction, which took them the better part of two months. Between Cleary’s original studio in Boston and his new studio in Cambridge, they found enough space to store and build the piece. Cleary’s studio-mate, artist Andy Young, also a friend of Adamopoulos’, made himself available as an extra hand and a sounding board to bounce ideas off of as the project went on.

By the time of the opening reception, the last of Cleary’s panel paintings were being installed on site, and with a final tightening of bolts, all components were in place. The object took art “beyond the surface” in more ways than one—with the pencil marks that intentionally remained on the final frame, the group had exposed, in part, the mechanics of the structure. Cleary’s paintings, facing inward, offered their undersides to the elements, and a fresh experience to viewers passing on the outside of the piece. “What happens underneath can be breathtaking,” says Cleary. “[I like to keep the process] unpredictable and mysterious, and the underside is always surprising.”

The underside of the project itself, from the people involved to the timeline of their lives, has drawn me further into the world of these artists. I see this piece not so much as a finished product, but as the tip of an iceberg of conversations and private thoughts—personal ambitions and shared compromises—not to mention the many hours of physical labor and the inevitable periods of argument and reconciliation. The piece is physical evidence of a shared effort.

“We are all hungry to shape our surroundings in whatever way we can,” explains Adamopoulos. “We, independently, all have a diverse set of skills and interests and really have no choice but to create.” In speaking to each of these men, three distinct personalities emerged. Cleary: an artist, driven by aesthetic, concept, and beauty. Adamopoulos: adventurous, energetic, creative, thriving on the challenges of design. Severo: articulate, talented, a more technical mind, endeavoring to affect people positively through his work.

Through the Occupy 539 program, Matthew Paul Cleary, Andrew Adamopoulos, and Tim Severo have had an opportunity to collaborate with artists of a different ilk than they, and more projects will ensue. Adamopoulos and Severo will continue to build the house in Canada together, while Adamopoulos and Andy Young have been talking about launching a fashion magazine. Cleary, meanwhile, continues to work out of his studio and hopes for future projects with the group, especially through other public art competitions such as this.