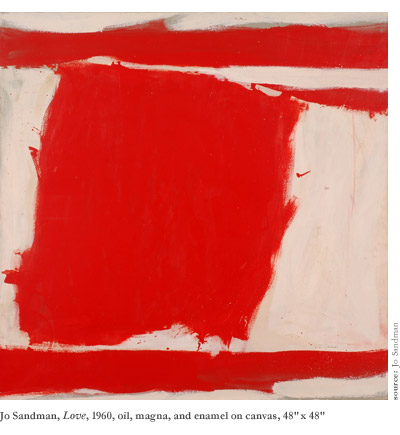

Jo Sandman slides another canvas from its rack, revealing sweeping gestures and bold red color. Painted over fifty years ago, Love captures not only Sandman’s innate ability, but the era of mature Abstract Expressionism, at the heart of which she was beginning to make her mark. In 1951, she was in residence at Black Mountain College alongside Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly. Following graduation from Brandeis University, she studied with Hans Hofmann in Provincetown and Robert Motherwell in New York. Artists connected to this highly abstracted mode emphasized the importance of the act of creating. And rarely have I encountered an artist who has lived that ethos more purely than Jo Sandman.

The paintings being pulled out from the wooden rack at her longtime home in Concord, Massachusetts—each like a snapshot from the artist’s history—are fully charged with energy. At once dynamic and meditative, her paintings are held together by formal properties that make them work. The gestural statements come directly from the interior of the artist—fast but deeply considered. Channeling Josef Albers, colors hold their surface and shapes cohere. When she looks at the work with me, she remembers her conviction and the intensity of art-making at that time in history.

“I would paint feverishly, then stop, pull away, smoke a cigarette. You study it for hours. Then you do something. Then you wait until the next day,” Sandman says, staring at a large canvas we exhumed. “Most of my time painting was studying the work. I had to make sure the surface stuck, that there weren’t any deep holes.” She shared her love of Richard Diebenkorn, especially the way he was both abstract but referential to the outside world, executing paintings that revealed less angst than his counterparts and were full of color. Growing excited by the conversation, she caught herself and laughed. “Clearly my heart is still in painting.”

Sandman received her MFA in painting at the University of California, Berkeley in 1954, and later received a teaching degree at Radcliffe College in 1956. During this time she met Walter Gropius, who employed her as a mural designer and color consultant at The Architects’ Collaborative. But by the late nineteen sixties, her artwork had begun to shift in profound ways. Feeling, as others did, that painting had already said what needed to be said, Minimalism became a bold counterpoint to Abstract Expressionism, fulfilling a need to see art as more formal and less psychological.

Sandman stopped painting, but without discarding canvases altogether. She began to fold them onto themselves to create a very pure—and yet sensual—body of minimalist work. Simple, beautiful, and highly structured, the unstretched cotton and linen even created a subtle chiaroscuro. She also became delightedly obsessed with industrial materials—an experience that allowed her to tap back into gesture. Laying down ropes of white caulk onto emery paper, she created drawings that managed to be both witty and serious, a kind of industrial painting on velvet. Cutting into insulation paper to reveal surprising beige tones underneath, she played with positive and negative form, creating works that were less minimal, more dialogical, and no longer self-referential. Logic, shape, shadow, illusion, and a touch of gestalt are always Sandman’s ingredients. The permutations of these elements are seemingly endless and often enacted upon unsuspecting materials.

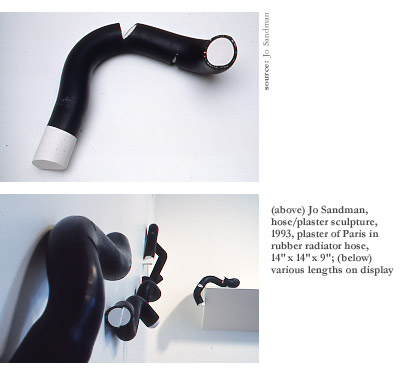

In 1993, while waiting for her car to be repaired at a garage, she was suddenly struck by a pile of radiator hoses, each at once organic and industrial. Filling them with plaster enabled Sandman to manipulate the twisted segments in myriad ways. When she cut into them, crisp white plaster at the core was revealed, like the inside of a cream-filled dessert. For some works, she scored their rubber coating with a knife—the scarification in African tribal art that had so inspired postwar artists. In her installations, dozens of plaster-filled sections of hose in various lengths, articulated in various postures, were configured to pair off as they crawled along walls and formed communities along floors. Organic and forceful, much like her paintings forty years prior, the unruly automotive hoses are bound together by Sandman’s signature logic. And like all her work, they are unreasonably beautiful.

Jo Sandman’s experimental approach continues to drive her artworks in ways that are fresh and meticulous. The force within is attenuated and intentional, removed of ego and always pleasing to the eye. That holds especially true in her recent bodies of work, which engage the ephemeral and the spiritual in ways that are as surprising as they are precise. Having known of and written about Sandman’s work for years, I had yet to mine her repertoire so deeply. Much like the artist herself, there is an uncompromising elegance to every piece she creates, no matter how pedestrian the original material. For me, her work is utopian—egoless, formal, spirited, and beautiful—if only the rest of the world could catch on.

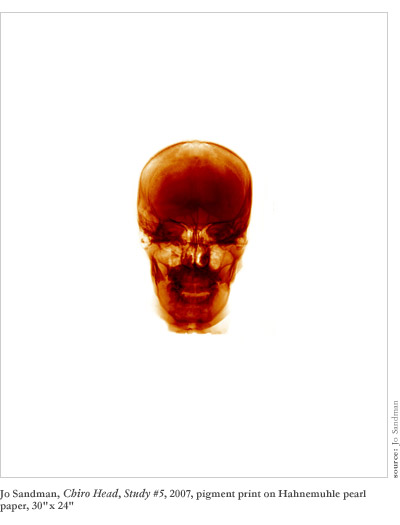

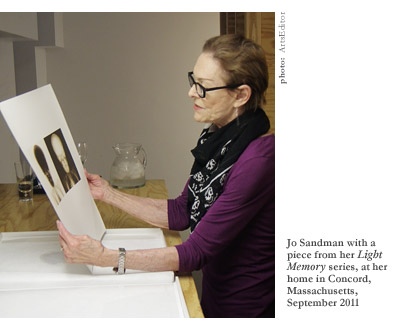

Visiting her Brickbottom studio in Somerville, Massachusetts, I am greeted by ghostly apparitions that glow and hum right off the walls—the works of Sandman with which I am most familiar. Since 1995, photography has become her primary medium. Working with found photos and x-rays (an interest sparked by her own carpal tunnel x-rays and the idea that one could move beyond purely diagnostic data to an interpretation beyond bare bones), Sandman produces work with both expressionist and illusionistic qualities.

The objects dominating her recent series were found while walking the beach over a decade ago. The rocks and coral reminded her of heads and faces, and she began to look for more stones and shells with those same tendencies. Back in the studio, she reshaped these fossils to accentuate their anthropomorphic expressions, suggestive perhaps of psychic automatism, enhancing unique characteristics and summoning identities. From this exercise a magnificent amount of work continues to flow. Converting these three-dimensional natural objects into two-dimensional photographic images—utilizing different techniques for each series—Sandman has created a paranormal population of alien forms.

For her series Twice, she doubles up photograms (contact prints created by placing an object on light sensitive material) of miniature found faces by copying them once on paper and again on a transparent surface. In this exercise, Sandman would say, a spiritual imprint is sealed. For a similar series, resurrected volcanic stones and shells reimagined as masks are printed twice again, this time with a shift in registration that adds depth and casts an eerie shimmer on the humanoid visages.

Memento Mori, Latin for “remember you must die,” is a collection of ethereal and ghostly Van Dyke brown photograms. A related series, Metamorphose, adds hand-drawn, idiosyncratic torsos descending from the floating masks. The archaic Van Dyke brown formula lends a different effect to the stones served stark white in Light Tracings, a series begun in 2002 that captures phantoms seemingly in the process of mutation. Close inspection reveals startling amounts of detail, including elongated chiaroscuro forming angles and eye sockets.

“All of my photo-based work speaks to the tentative nature of life, and the entire series serves as a reminder of our limited time on earth. This is probably evident in the work itself. At least I hope it is,” Sandman says wistfully. “The memento mori—reminder of death—theme has been used occasionally by many artists in their work over the centuries, sometimes as a scull on a desk or fading flowers or a candle burning low.” I ask her how this work connects to the rest of her oeuvre—her painting and her process work. “Possibly it expresses the desire, the attempt to push on through one’s existential dread, to struggle with the new,” she replies. I find this especially true in her extraordinary x-ray work, often shown in tandem with her Memento Mori series, examples of which populate her Somerville studio with skeletons.

With the right amount of purposeful—albeit subtle—manipulation, the x-ray works are intimate portraits, infused with a poetic life breath. The Internal Signs series showcases enormous, delicate skulls looming large on heavenly white backgrounds. The Light Memory series, created over a two-year period, alters human x-rays (from a source in California) by scanning them into a computer and manipulating them through Photoshop to remove scratches, dust, and tears. The contrast, density, and at times proportions are enhanced. The complied files are then output onto film and enlarged on photographic paper in a conventional darkroom. A final injection of sepia tones adds a sense of mystery but also spirit to the work, as if the skeletal image has been delivered gently back to the living. Cold medical data has been transfused with new life. Historically, x-rays were likened to a spiritual fourth dimension and a psychic ability to penetrate objects and thoughts. This is never lost on Jo Sandman.

Chiro, a series of eight photographs, begins with chiropractic x-rays used to indicate the axial plumb lines of the head, which determine degrees of non-alignment. Sandman converts these images into composites, each 30″ x 24″ in size. In her statement about the artwork, she writes, “Color is used to increase the sense of burden of each image, as if they carry their own history of misfortune.” The color to which she refers is so fantastic it defies a likeness. The red, orange, yellow, and burnt umber hues fluctuate with the density of the bone. It’s as if the skulls are lit from a fire burning somewhere within the unseen body. Having presented us neutral tones for so many decades, and with such success, Sandman’s bold return to color is possibly a one-time treat. Or perhaps it’s a signal of what’s to come.

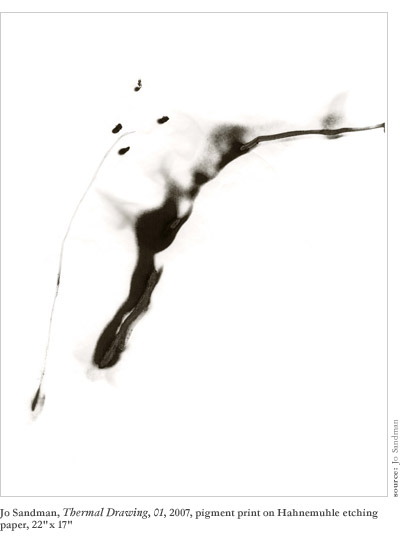

Returning to the minimal black and white that has dominated the later part of her career, Sandman’s more recent photographs are in fact drawings, and reference her earlier works as a painter, employing a minimal aesthetic based on formal restraint. Through the use of a heat source—incense—her Thermal Drawings capture the artist’s hand flying off the surface of fax paper, which is later scanned and reprinted on archival etching paper. With these drawings, Sandman presents an impulsive, unimpeded, gestural counterpoint to her preconceived and exacting x-ray works. In other words, a celebration of life.

Continuing her work with faces and masks, Jo Sandman infuses life into the inanimate as only an artist who has lived such a prolific career can. Always true to the act of creation (and recreation), she has given voice to a multitude of materials, which have made their way into over a hundred shows and exhibitions and dozens of private and institutional collections around the globe. In fact, every era of Sandman’s work has been collected—a testament to her expertise across a wide range of media, concepts, and aesthetic convictions. The Boston Public Library owns a suite of Memento Mori. New York University has collected several artworks, as has the Dallas Museum of Art. Massachusetts Institute of Technology has collected her folded work. The Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University has collected a tar drawing from her Orientations series. The DeCordova Museum, which gave Sandman the first solo exhibition of her work (oil paintings) in 1952, owns several of her pieces, as does the Danforth Museum of Art, which presented a fantastic 35-year retrospective of her work in 2008, curated by Katherine French. She also has an ongoing summer connection with Provincetown, which continues to inform her art-making.

In the corner of her Somerville studio, an installation project is currently underway—a work that seems to recall her installations of two decades ago, yet promises to lead with light, not shadow. The white, mirror-topped sculpture stands are painted with bold colors on one side, casting a ray of color onto the white wall behind them. Sandman never stops moving as she shows me its many possibilities. I don’t suspect it has ever occurred to her to not create.

Sandman taught painting at universities long after she put down her brush, and I can’t help but consider what a return to painting would look like, a temptation she has hinted at herself. What would a lifetime of the manipulation of commonplace objects bring to her canvas? Perhaps we would recognize the work as her own for its gently contained life force or its beautiful logic. We might recognize an ephemeral quality and the hint of something sublime. Most likely it would present us with something we had never before considered, at least not in the way Jo Sandman would reveal it to us. Of her many gifts, perhaps that is her greatest—an ability to find and extol that which we could never see on our own.