In the football stadium below the terrace on which the stately gray buildings of Boston College sit, the meat-eating Eagles are preying on the thistle-eating Cardinals of Ball State University. The partisan crowd of BC fans, white suburban folks of Irish ancestry for the most part, wear gold t-shirts emblazoned with the image of a red raptor and the word “Superfan” in cursive across the front. It’s a most unchristian thing they’re doing—more akin to watching the lions eat the Christians in Rome, really, than to turning a cheek or loving a neighbor as thyself. And Lord knows the clan’s been less than kind and somewhat cruel to people of color in Boston in the years since throwing the Brahmins off their backs. Yet who’s wearing a high percentage of the red and gold uniforms on the field but African-Americans recruited from neighborhoods like Dorchester and Roxbury, which were created in part by the sort of segregation imposed before and after the notorious Boston busing crisis of thirty years ago?

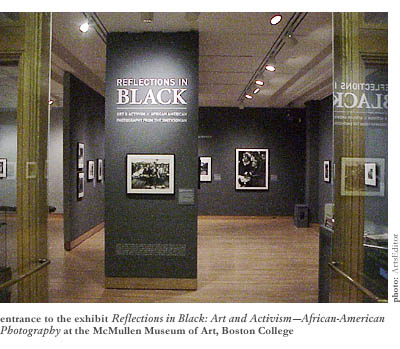

It’s at least mildly ironic, and it is thoroughly admirable even if it’s also superficially hypocritical, that the McMullen Museum of Art, entombed in one of those granite edifices on the terrace, is holding the mirror up to nature to let her see Reflections in Black: Art and Activism—African-American Photography, on display through December 7th. On this straightest and whitest of college campuses, the exhibit of “over 130 images from the civil rights era to the present,” as the caption on the wall says, could be a conspicuous gesture of goodwill toward people who have systematically been denied decent housing and access to good schools by the Irish-American gentry who only a generation before overthrew their own Yankee oppressors in Boston to gain political freedom.

For Negrophobes, Rush Limbaughians, and anyone who for reasons of geographic isolation has not taken the slightest interest in the history of African-American politics and culture—a tale of plight, fright, and the fight for rights—Reflections in Black will seem like an infuriating poster campaign for an undeserving people. But none of those freaks, if they actually exist, is likely to stumble upon the exhibit. For the rest, it will serve to solidify the knowledge base and to please the heart and mind.

They’re not colorful, glossy reflections for the most part, because they were taken by African-American photojournalists interested less in dazzling eyes than in keeping them on prize, represented always by people—whether in photographs of sung or unsung black heroes of their times. But they aren’t dull or pedantic, either. Thematically organized in rooms and suites of galleries labeled social justice, culture, community, and faith and devotion, these photos offer a fairly comprehensive panorama of post-bellum life in the United States for the more than 30 million descendants of black slaves.

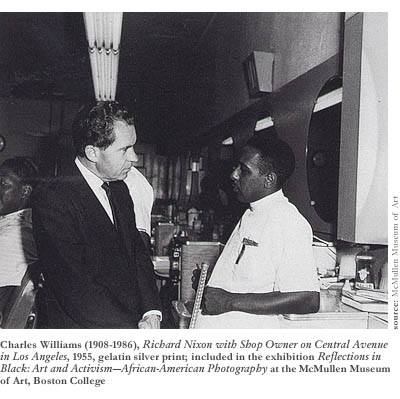

In an excusably polemical gesture, the curator—Professor Deborah Willis of New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts—has placed the topical social justice pictures in the first room of the exhibit, some of them visible from the hallway through the glass doors. Featuring a small but star-studded slew of photos by Jack T. Franklin, Ernest C. Withers, and others, this section includes images from the 20-year peak (from the mid-’50s to the mid-’70s) of the Civil Rights movement. Those images include several of Martin Luther King, Jr. and his clean-cut, soft-spoken associates; several of the regal and somewhat imperious firebrand Malcolm X (trademark glasses, goatee, and all); and several of the black-beret hipsters from the Oakland area who dubbed themselves Black Panthers. Three influential forces representing divergent attitudes about the best means—violent insurrection or nonviolent resistance—by which black people would attain their inalienable rights and opportunities and the abundant goods and services that come with them in the American-dream package deal.

It’s almost unfair that Willis has placed these photos of the famous black political leaders here near the entrance, because it’s nearly impossible to keep from looking closely at each one, which makes it harder to spend quality time with images from the other three sections that sometimes have more going for them aesthetically. Who wouldn’t want to linger at the very first photograph on the wall facing the door: Martin Luther King, Jr. and his closest assistant, Ralph Abernathy, chuckling in unison with Sammy Davis, Jr., at a scene outside of the picture plane in the front row at an outdoor rally in Los Angeles, fan-like palm fronds bending in the ocean breeze in the background? Wouldn’t you want to squint for a while at Rosa Parks addressing a crowd in Montgomery, Alabama, a few years after her legendary act of civil disobedience on a bus in that city activated a movement that led to the passage of the Voting Rights Act under President Johnson? For the literati, there’s the satisfaction of recognizing without a glance at the caption the writer James Baldwin, grasshopper-eyed, elegant, and superior, descending the emancipated steps of the Lincoln Memorial, perhaps, with handsome—or maybe “pretty” is the word—Harry Belafonte and his drop-dead gorgeous Queen of the Nile wife Julie in 1963, the day MLK delivered his immortal “I Have a Dream” speech.

Celebrity photos gave credit to the King-led part of the Civil Rights movement that focused on working courageously within the system on voter registration drives, school integration efforts, and workers’ strikes. The exhibit features photos of all these projects. The opposite could be said of Malcolm X’s black nationalist and the Black Panthers’ black power projects that this section of the exhibit represents—seeing hope of enlightenment among the fed white masses, they struggled against the system, trying to knock it over, and didn’t play up to the media with efforts to look assimilated. Hence, white folks who’d seen newspaper pictures of a regular TV entertainer at a King-led Washington demonstration wouldn’t have said, on seeing a photo of Mohammed Ali resisting the draft at the encouragement of Malcolm X or a photo of Bobby Seale or Huey Newton guarding with a machine gun a free breakfast for Oakland children, “I’ll be danged if I ain’t seen that colored fella on the Ed Sullivan Show!” Sammy Davis, Jr. didn’t hang with Malcolm in Harlem or Eldridge Cleaver in Oakland, after all.

Maybe it would be wise to look at Reflections in Black: Art and Activism—African-American Photography in reverse, starting with the faith and devotion section in the basement galleries, where documents of unsung African-Americans in the throes of religious ecstasy and the serenity of solemn worship can be seen. Maybe, starting from the cellar, where African immigrants to America in a figurative sense began anyway, a person could grow or renew respect for the ways of black folk that would culminate upstairs, after tours of the community and culture chapters, on higher spiritual ground. Take the baptism of a dark-skinned woman in a white robe flanked by black-clad black men in a gray river in a photo by Keith M. Calhoun, for example—a photo that, like almost all of the 130 shots, is humbler and more representative of the tradition of entrenched poverty for being black and white. Or take the black Muslim woman peering with beautiful leonine eyes through the slit of her burka in a Chester Higgins, Jr. photo, her head filling the entire plane of the portrait, her rejection of American materialism tacitly expressed. Or the faith healings in the pews of the Baptist churches—a woman writhing and speaking in tongues—or the sea of dark faces shrouded by white robes at a huge Islamic service in Chicago in the 1960s. Photos of a people reaching for otherworldly experience from a planet dominated by business-like people of pallor so frighteningly stiff and official that many people of color were eventually led to suspect them of being aliens or devils.

Walking backwards through the lower-level galleries toward the stairway to heaven, a person of people, of any color—an established member of the black intelligentsia who studied with Cornel West and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. at Harvard, say, or an engaged young woman from the METCO program that sends black youths to the burbs for a pricier education—could admire the community section as well. William Earle Williams’ haunted photos of historically significant sites in the South, from the ruins of a Tennessee fort built and defended by black soldiers in the Civil War (for the Union side, you’d think) to a scene on Jamestown Island in South Carolina, where the first African-Americans landed, albeit in chains. Linda Day Clark’s refreshingly current photos from the 1990s, including one of several young shiny-faced women, unwed teenage mothers from “a home” perhaps, styling together with their babies on the stoop of an apartment building; and another of an unassuming little black girl holding a pale, suggestively stiff-limbed Barbie doll, unaware of the tragic ironies in the picture. Very cool, and probably in need of more like-minded, contemporary company in the exhibit, because they speak more to our moment than the civil rights and churchy pictures, which might be regarded as stereotypical by this time.

Or Earlie Hudnall, Jr.’s three portraits of old people, highlighted on a single wall for their aesthetic mastery. An old black leather-faced cowboy smoking on a front porch, his Stetson and African face in cameo profile. The ancient, likewise-leathery Lady in Black Coat, in print do-rag and fake fur coat sleeve, turning around on a park bench to look at the camera, a great somber dignity to the lines of her face—one of those noble, atavistic crones, completely of the African experience somehow and probably never a visitor to the white world, whom a worldly person can see on a stoop near Grove Hall or Uphams Corner some summer day. Then a portrait of Aunt B with a do-rag and light woolish coat smoking a cigarette, a brown paper bottle-shaped bag that speaks for itself on her lap. Pictures that are as much about texture as anything—but texture of experience as much as texture of photographic representation.

It begins to seem to the gallery-goer like a marvelously abundant exhibition of photographs by now, where everything merits a meditative, admiring pause. The Jeffrey Henson Scales shots of the fellas jivin’ at the barbershop, center of African-American male culture for all these years. The four photos from Chandra McCormick’s Louisiana series, featuring the traditional social-realist documents of rural poverty, a la the work of white radicals from the WPA projects of the 1930s such as Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange—an interior of a poor family’s cabin, portraits of sugar-cane field workers with impassive yet stubborn faces. Photos that look like they were shot not during the past 20 years but in the 1930s, as if to suggest that the more things change, the more they stay the same.

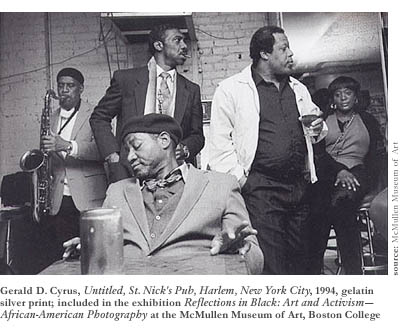

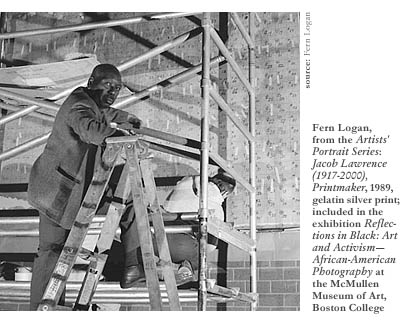

Backing through the gallery toward the social justice wing, the person of indeterminate epidermal pigment and complicated sensibility passes through the culture section. It’s not the kind of culture s/he’s come to think of, as in anything that a whole lot of people from an identifiable group do. It’s the traditional, snooty definition of culture being used here, as in high art. And, not surprisingly, this being African-American high art, the images depict more musicians than anything. True, there are photographs of scholarly activist Angela Davis, The Color Purple novelist Alice Walker, and visual artists Romare Bearden and Jacob Lawrence. (Surprisingly, not a single shot of Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes, no sign of Paul Laurence Dunbar, maybe glimpses of Richard Wright and Toni Morrison.) But mostly it’s musicians. Great shots, too, of the players in action reaching the heights of joyful expression. Jazz singer Sarah Vaughan singing “Autumn in New York” or “Lush Life” to a somewhat beatnik white audience in the early ’60s. B. B. King beaming with Elvis Presley arm-in-arm for the camera in their mutual Memphis, both of them dressed to the uptown nines. Mahalia Jackson, civil rights activist who worked closely with Martin Luther King, Jr. singing about the River Jordan or the Lawd Almighty to the heavens in the L.A. Coliseum. Duke Ellington in the club car of a train watching his horn section play cards on the way to the next gig. Billie Holiday singing to Count Basie’s accompaniment at the ivories, his big band brassy in the background. John Coltrane, always somber and completely lacking in charisma in photos, in a studio where he’s been recording on his soprano sax the most moving squawks imaginable—in a purposely dissonant style like Walt Whitman’s barbaric yawps.

Back, back, back through the exhibit moves the saturated observer, who has decided to defer the dream of the civil rights photos till the very end. Something is missing from the exhibit—more photographs of modern urban African-Americans, maybe; perhaps a sports section that would put Jackie Robinson, Michael Jordan, and Venus Williams in perspective. But it’s been great already, and here come the imposing civil rights pictures. But just before backing into the Black Panthers and finding a raised fist in the face, this anonymous and by now enraptured person, the one whose experience of African-American culture may or may not be limited to an acquaintance or two at work, turns to see several photos of black men on Death Row. Not a fortuitous place to end—but inspiring for the rousing photographs of revolutionaries to come and capable of evoking a good measure of civic pride, too, because these photos of Death Row inmates in the states of Florida and Texas came from the camera of Lou Jones, a Boston photographer, and they work chillingly well, especially when supplemented by explanatory biographical captions. They make a person hope that life for African-Americans in Boston isn’t—or doesn’t have to be!—quite as miserable as it’s cracked down to be. A youth from the down-and-out ‘hoods of Roxbury, Dorchester, or Mattapan can grow up to be a photographer, after all, even if in the service of the continuing struggle for social justice. Granted, not a line of work that usually pays very much.