It’s New Year’s Eve, 1984. My true love and I are standing inside the Sistine Chapel in Rome. The place is packed with tourists. Michelangelo’s ceiling fresco is in the process of being cleaned of grime and restored to its original clarity. The details are still pretty murky. But as surely as the Pope is Catholic, the most famous scene of the painting hovers above us: The Creation. Sinewy Adam, freshly formed from clay, leans back languidly in his inexplicably nonchalant way, extending his well-proportioned left hand toward his sagacious, gray-bearded maker, who cradles Eve and the kids on the cloud. I’m mumbling into my true love’s ear some ironic comment about the iconography of the patriarchal papist powers. She doesn’t want to hear it—good for her—and isn’t that thrilled with Italian Renaissance art anyway, preferring the restraints of the Dutch to the flourishes of the Italians. So she’s looking around more than up, which is why she lets out a little squeal of delight. See, she’s just seen her father’s best friend from their grad school days in Cambridge. He’s over there in the middle of the chapel, looking directly up with his wife and two sons at a defining image of Judeo-Christendom. He’s a sweet man, a Jewish professor of English literature who got out of Central Europe before the Nazis who hauled off his extended family could haul him off to the camps, too. We will spend New Year’s Eve with him and his family in Rome, and as the years go by he’ll send us bittersweet installments of his memoirs about relatives who died in the camps.

That’s what I remember not long after I walked into the Pucker Gallery on Newbury Street one Saturday in November to see In a Different Light: Genesis in the Art of Samuel Bak (on view until Dec.31); and it’s the background I can’t help but see the exhibit against. For there they are now, in painting after painting, appropriated depictions of Adam himself, in the unmistakable guise of a hunted-down European Jew of his early middle years, assuming that same posture I saw in person on the Sistine ceiling and in countless reproductions before and after that. In Bak’s bizarre paintings, which strip down Michelangelo’s sensual settings of the Genesis stories and dress them back up in ghastlier garb, it’s as if my father-in-law’s friend has been lifted up into the fresco he was staring at. Adam, a pallid, stubble-faced, burr-headed, gaunt, and hopelessly impassive figure, no longer relishes a languid nonchalance, and no longer counts on an imminent touch from the warm hand of God.

Bak makes liberal use of surrealist symbolism to drive home his never-exactly-subtle visionary point about the Holocaust as proof of humanity’s estrangement from the divine. He puts monstrous steel-gray industrial images of the Second World War into the dusted elemental blue, brown, green, and rust-colored Mediterranean settings of Michelangelo’s fresco, pitting the synthetic against the natural in a traditionally emblematic way. With illusory precision he paints that familiar image of the Vatican’s Adam in the foregrounds of Biblical desert landscapes that have been visited by modern nightmares, tingling the spine with unexpected cut ‘n’ paste juxtapositions, raising goose-bumps, and crossing cerebral and emotional wires with therapeutic skill.

In Adam with His Own Image, dressed in a brown, hard-laborer’s uniform unbuttoned to the waist to reveal the long-johns he wears against the cold, Adam reaches that famous hand out, not to God’s this time but to an upside-down sketch of his own hand on a stretched canvas. In Searching, Adam is painted as a crumbling, stone, shaven-headed sculpture of his former self on a barren hillside extending that hand to no other image at all—and the image of his own hand appears this time as a crude wooden cut-out, like a weathervane or an index-fingered advertising gimmick, on a rickety stand of sticks beside him, while the image of God’s hand, some distance behind him and up the hill a ways, points its now-accusatory finger into the noble face of a large stone bust of Adam gifted with its original healthy head of hair. In Open Door, all that’s visible of Adam’s form, through that open door in the ruined, roofless wall, are the extended left arm and the bent left knee it always rests on (a blackly comical twist of this ornery painter’s wrist)—and now the extended hand of God is an enormous, fractured stone cast of a hand that actually forms part of the wall, plumb-level bricks and all, its right index finger resting on the bare wooden lintel of the door—a bluish hand against a rust-colored Middle Eastern desert landscape good for growing Old Testament prophets on.

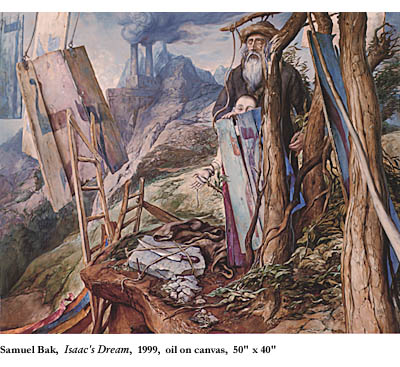

Adam isn’t the only star of the exhibit, though. Samuel Bak has done equally provocative depictions of the stories of Abraham and Isaac as well, including Isaac’s Dream, featuring a deeply sad-eyed would-be-sacrificial boy looking at us from the clutches of his prayerful old shuteyed father on a Mt. Moriah that now sports a smokestacked camp crematorium on its slope and a shred of paper rainbow, some symbolic ladders (ubiquitous in these paintings), and an uprooted tree in the foreground—brazen indicators of the broken human condition. Bak has “iconoclasted” the image of the ancient Noah, too, lying him, in Noah’s Dream, on the stony, untender ground with his flowing white beard and Godspelled grimness still intact from the severe pages of the Old Testament, but putting an unbuttoned brown coat on him and laying beside him an umbrella and fedora, granting him the gruesome identity of a distant, doomed descendant, an assimilated Jewish citizen of Europe dozen of begettings from the beginning, that he will be shocked to awaken to, his dream-come-true higher ground of Mt. Ararat cluttered with a fantastic painting-within-the-painting collage of disparate images in the background—a paper-strip rainbow tacked to a stick frame that also supports a painting of the everpresent crematorium smokestacks and a quiet white dove of peace, only now with real black smoke fuming into the actual dark blue sky from the painted image of those smokestacks, while one ladder rises from seaside rocks in the background and another floats disembodied against the better judgment of gravity up into the sky and right on out of the picture.

There’s a great Madonna-like painting of a Rainbow Angel in this massive, almost cramped show. There are a fabulous few surreal Biblical-landscape still-lives (of water pitchers and pears like none I’ve seen before) that borrow from the Cubist collages of Picasso and Braque. There are a lot of angels in surreal circumstances they never bargained for in the Bible, usually with drained expressions, sallow complexions, and metal wings, even the healthy one of Reflecting apparently having an identity crisis as s/he sits near a huge stone fossil of Noah’s shipwrecked ark on Ararat before a mirror that projects her own image onto the other side of the mirror. These strange paintings manage at once to be historically profound, psychedelically intriguing, aesthetically enriching, and spiritually affecting.

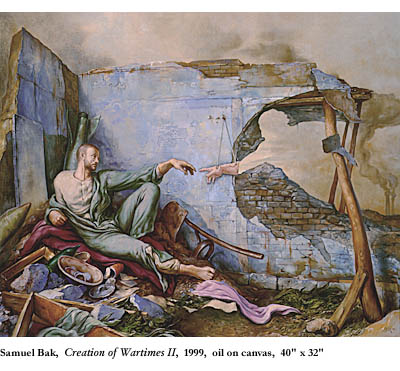

Eve, Isaac, Abraham, Noah, Joseph, God, and others make significant contributions to the Pucker exhibit, but the real star of the show is Adam. In Creation of Wartimes II, he reclines, in that ideal model’s pose, on a pile of rubble, in the roofless corner of a bombed building, grim uniform and burr haircut betraying his political-prisoner’s status, the image of God miraculously represented by a hole blown out in the wall in the profile of Michelangelo’s deity. God is not completely absent here, though, not just a hole-in-a-wall profile through which the blue sky can be seen, because at least the famous hand looks real enough—even as it swings by a string from a nail in that ruined wall, the two ominous chimneystacks that billow smoke in the distance taking the resonant absurdity to another level.

The dream-induced appropriation of Michelangelo’s images continues in the depictions of Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the Garden. In Banishment and Banishment II both, the shamed couple cowers in frescoes on a ruined wall, the lower halves of their bodies depicted not as part of the frescoes but as paintings on stretched canvases and as broken, freestanding sculptures. The sallow, expressionless angel with metal wings bears a rifle in these paintings, occupying anonymous and ineffectual positions, unable in his condition to do anything about the expulsion. A bomb shell leans against one of the sculpted legs, and the canvassed depiction of Adam’s legs is ripped, as if by shrapnel, at the corner. Not much is left on earth to live for, and the banishment is so far in the past now, and so overshadowed by millennia of succeeding demonstrations of our alienation from Paradise, that the horror and shame of Adam and Eve look like relatively nice problems to have. At least they still seem to have their health.

Is the Holocaust a perfect reminder of how far we are from getting back to nature in Eden? Are Adam and Eve not being turned away from Paradise but running from the corrupted earthly setting where such a thing as genocide can happen? Are the appropriations of the Michelangelo paintings suggesting that salvation and redemption, possible through the creation of beautiful art back in the Renaissance, are two or three veils of illusion or epochs of atrocity away from us now? Is it “fair” for a painter to appropriate one legendary art-history figure in so many paintings, giving a cutting currency to the ancient artifact and juxtaposing it to assorted combinations of anachronistic imagery? Are Bak’s paintings, seen up close, not only amazing with their bold technical detail but downright intimidating with their thorough and living knowledge of Biblical arcana? And are they not also, seen from a disinterested distance, unfortunately just a tad reminiscent of the myth-mad, archetype-anxious, unintentionally funny covers of albums by heavy-metal rockers?

Tikkun, in the Jewish mystical tradition, has to do with humanity’s obligation to put the finishing touches on God’s incomplete creation. The word Tikkun itself appears, according to captions, in the original Hebrew in many of Bak’s paintings—even in paintings that present a hopelessly fragmented existence for people on earth. It’s an impossible but inspiring challenge—to put this world back together, heal nature, and get back to the garden!—that Bak has accepted. It must have something to do with his past. For when Samuel Bak was a child in Poland, a few years before the genocidal destruction of his own family and his own narrowly-survived internment in a Nazi labor camp, his mother used to enchant him with her readings from Genesis. He honors his mother by treating those tales to his surrealist paintbrush, looking back in full artistic force—with visionary eyes, using the talent she fostered—to the settings she magically invoked.