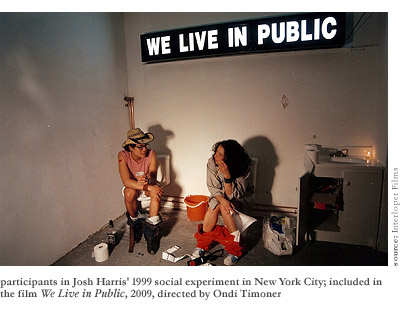

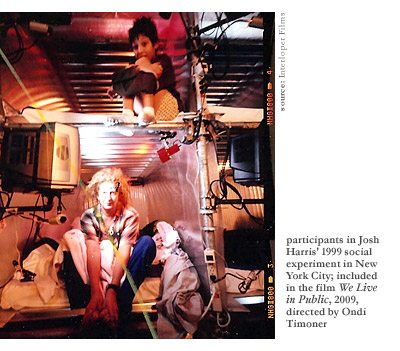

Few of us today know the name Josh Harris, the one-time dotcom millionaire with a penchant for Gilligan’s Island and staging public “live-ins.” In many ways, Harris’ antics throughout the 1990s reflect the kookiness of the Y2K era, a freewheeling ethos of technological innovation, financial revelry, doomsday speculation, and eerily coordinated mass suicides (the Heaven’s Gate cult in 1997 probably the most notorious of this time). His most audacious experiment involved 100 people living in pods in New York City during December 1999. The futuristic melange of capsules looked like a cross between Hollywood Squares and church-camp bunking, each pod specially equipped with a webcam and television monitor to record the minutiae of voyeuristic living celebrated in Harris’ social experiment. Participants watched and were watched in the act of watching each other. Their lives were wholly “public”—or more aptly, Orwellian—in every sense of the word. And behind the virtual curtain, big brother Harris, then in his late 30s, was observing as his experiment began to unfold.

Participants of the art project Quiet: We Live in Public, as it was dubbed, observed each other sleep, eat, shower, philosophize, fight, and shit. No aspect of their underground selves escaped the camera’s eye. Showers, toilets, and pod promiscuity were open viewing. Sex and debauchery of course were rampant. This “human terrarium,” as it was called, featured a banquet-style, improvisational mess hall, fully stocked bar, and a mysterious questioning room where participants would be intermittently whisked away for interrogation by makeshift authorities. Most bizarrely, the terrarium offered a shooting range with a vast array of firearms, where pod people were regularly encouraged to cap off machine-gun rounds. As an experiment in human behavioral psychology, Harris’ project, we can only surmise, seemed to be probing one forward-looking question: How will full immersion into life “online” change the way we see ourselves as private subjects? In the end, however, the Federal Emergency Management Agency raided the commune after just 30 days of virtual living.

In his most revealing venture, Harris spycamed his own life the following year. He lived under surveillance for six months in his apartment with his girlfriend. Viewers were even given a first-hand glimpse of Harris’ bowel movements, toilet side up. He hid nothing from the camera’s unflinching gaze. Interestingly, the “actor”/audience relationship that took root in this interactive environment seemed to grow more and more self-reflexive as the weeks passed. Viewers would proffer advice vicariously on everything from affairs of the heart to dinner recommendations, pro bono pizzas oftentimes showing up at Harris’ door. But some months into the experiment, Harris discovered an irrevocable flaw in the virtual self he had manufactured: the viewing audience had slowly transmogrified into a kind of online superego, a moral conscience that worked to undermine any sense of genuine intimacy between him and his lover. His relationship deteriorated, his private sense of self dissolved, and he suffered a mental breakdown. Needless to say, his Web site shut down soon after this collapse. Harris disappeared from NYC and media life a lost and broken man.

Ondi Timoner vigorously charts the melodrama of this rise and fall in her new documentary We Live in Public, which won the Grand Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival this year. It is well-crafted and well worthy of the metaphysical questions Josh Harris’ prescient experimentations implicitly raise: What is left of the private—individual—self in a world solely defined by the hyperreal? Has online social networking revolutionized or recidivated human interaction? What Platonic cave has this new virtual world of interconnectivity led us down?

Those interested in Platonic questions with a virtual twist will enjoy We Live in Public, even if the film does at times lionize its hero. Timoner places too much weight, in this sense, on Harris’ genius for unfettered self-aggrandizement, as if to suggest that the simple willingness to humiliate oneself publicly is sufficient claim to the visionary label she so readily attributes him. What is more, Timoner’s Chinese whispers about Harris masterminding the cultural developments that resulted in reality television seem rather dubious for similar reasons—especially since the formative concepts for big brother and reality television, for instance, date back at least to the Dutch television series Nummer 28 in 1991 and MTV’s The Real World in 1992.

This is not to say that Josh Harris didn’t live and think dangerously. He did, using technology (at times with great bravado) to challenge the many slack assumptions built into the private/public divide we’ve inherited from the pre-Internet world. Harris’ experiments with virtual living previsioned, according to Timoner’s interpretation at least, today’s brave new world of Facebook and Twitter. Such sites have come to mediate our sense of self with the larger social sphere of online networking, a virtual world in which our private interests—and our inmost preferences—are owned by the media companies that we ultimately empower. The potential tragedy of this irony is perhaps, then, Harris’ most compelling insight: once we’ve consigned ourselves to living truly “public” lives, we consent to a form of tyranny that reduces private life, and the individual self on which that sense of self is based, to a quaint, if not nostalgic, encounter with times past.