The day my mother gave me my first box of crayons is still, almost 30 years later, one of my most vivid childhood memories. When I opened the top of the stiff cardboard carton and revealed those sixty-four perfect, waxy sticks of color poised and ready for use, it seemed as though a whole new world of possibilities had been presented to me. All I had to do was decide which color to choose and make the first mark.

A visit to Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art, where an exhibition of the work of Brazilian street artists Os Gemeos is on view through November 25th, goes a long way towards reviving these giddy memories of youthful creativity. Bursting with vivid color and pulsating patterns and laced with humorous asides and hallucinatory dreamscapes, this compact exhibition of 11 works in the museum and two temporary public murals executed within the city is perhaps best described as a joyous, raucous encounter with two of Peter Pan’s Lost Boys. Eternally youthful and full of hope, Os Gemeos’ imagery cannot help but make you smile as it melds rural Brazilian folk traditions with the international urban idioms of hip-hop and street and graffiti art.

Os Gemeos, or “the twins,” were born Otávio and Gustavo Pandolfo in São Paulo, Brazil in 1974 and grew up in the bustling, multicultural, crowded, and often chaotic neighborhood of Cambuci. Interested in art from an early age, the brothers cite the arrival of hip-hop culture in Brazil in the mid-1980’s as a formative influence on their sense of aesthetics. A copy of Charlie Ahearn’s groundbreaking 1983 film Wild Style was a prized possession, introducing the Pandolfo brothers to the tenets of hip-hop style in everything from dance and dress to music and art. The brothers quickly became fixtures of São Paulo’s vibrant street art community, scattering their tags across the bustling metropolis of millions of inhabitants and quickly catching the attention of pioneering American street artist Barry McGee, who encouraged the brothers to pursue their art full-time. McGee was a pioneer in incorporating figuration into street art, and it was through his influence that they began to experiment with the brightly attired, yellow-hued punks and hoodlums who have become the trademark characters within their mature style. Although the brothers continue to live and work in their native city, their art has achieved global recognition. Os Gemeos’ mischievous figures adorn both public and private spaces from Miami, New York, and Los Angeles to London, Berlin, and Ayrshire, Scotland.

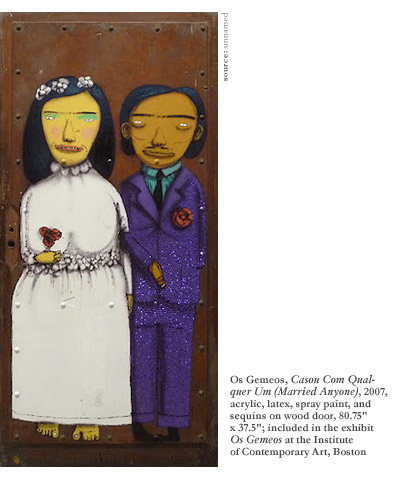

Drawn exclusively from private collections, the artworks at the ICA reveal the brothers’ major preoccupations with color, pattern, repetition, and humor. The exhibit opens with 2007’s Casou Com Qualquer Um (Married Anyone), an image of a bride and groom standing arm-in-arm and looking forward, as if posed for a formal portrait. The bride is rather conservatively dressed—aside from two garish streaks of green eye shadow—while her groom, on the other hand, sports a purple tuxedo that shimmers from the layer of sequins that Os Gemeos have carefully applied over the paint surface. This is a technique that recurs throughout the brothers’ corpus, and the effect adds texture, depth, and a sense of whimsy to their work, while also referencing longstanding artistic traditions, such as mosaic, which it recalls and closely replicates. Casou Com Qualquer Um is executed on a discarded wooden door, another practice that the brothers often employ, and which creates continuity between their public works and those pieces intended specifically for the gallery. By painting what we might consider “easel paintings” onto the sides of discarded doors, pieces of reclaimed buildings, and other urban detritus, they are able to retain for their art a sense of placement within the community and its collective space.

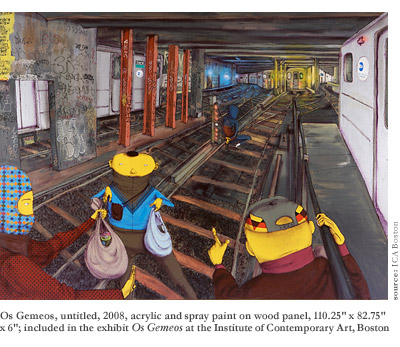

Although Casou Com Qualquer Um does introduce a number of elements that are common occurrences in the brothers’ work, and although this bride and groom are immediately identifiable as the work of Os Gemeos, it seems fitting that the painting is separated from the rest of the exhibit in a small entry vestibule. This earnest, somewhat awkward couple is poised on the threshold of adult life, lending added significance to the door on which they are painted. The playful, impish, and naughty figures that populate most of the rest of the paintings on display are, on the other hand, still decidedly childlike, finding their joy not in growing up and settling down, but in small acts of creative rebellion or within the limitless realms of their own dreams. In an untitled work from 2008, for example, three concealed youths inhabit the tunnels of New York City’s MTA subway system. One figure offers shopping bags full of fresh spray paint to his compatriots as the three prepare to tag the subway cars parked nearby. And in another untitled work, from 2012, a young boy in a knit cap appears to be swimming or perhaps drowning amongst the various images of his imagination. He is surrounded by a milky sea of opalescent color that is filled with fantastical doodles—animals, people, cars, and various other things occupy the space around the boy, suggesting both the fertility and nearly limitless possibilities of a young mind and also the danger that is posed when there is no outlet for such creativity. Os Gemeos’ preoccupation with the act of making art is clearly self-referential, but it also speaks to the larger creative impulses of society, particularly amongst youths, who are so eager to “make their mark” or otherwise exert some sort of influence over the course of their own lives. Viewed through this lens, Os Gemeos’ figures are essentially positive figures of change and creativity. Rather than accepting the metropolis as it is, they are able to change it, beautify it, and make it their own. Although this is accomplished through illicit and transgressive means, the end result—as portrayed here—is still one of joy, beauty, and ultimately hope.

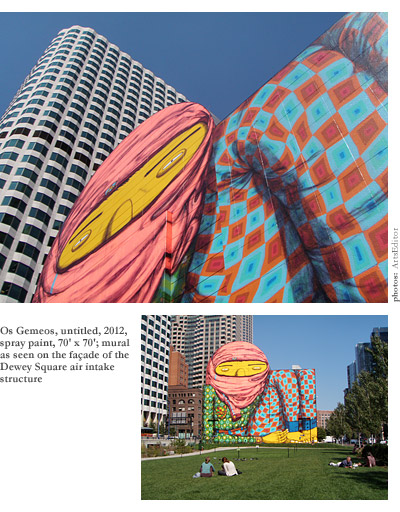

As engaging as the ICA presentation is, it is upon leaving the museum and looking at the murals in Dewey Square and on Stuart Street that one truly comes to appreciate the genius and success of Os Gemeos. These large-scale murals interact with, energize, and help to shape the space in which they are located, and are certainly amongst the most engaging public art to be installed in Boston in recent memory. The hooded, crouching figure depicted on the side of the Big Dig ventilation station in Dewey Square transforms the area from a barren and windswept intersection into a space alive with color and imbued with narrative. The artists have brilliantly made use of the rather unconventional shape of the building, turning its large, offset semi-circle into the head of what we can assume is a fellow graffiti artist. Having tied a bright red jacket around his head and face—both as protection from the fumes of his spray can and as a method of concealing his identity—we appear to have caught him at a very bad time. Interrupted at his work by the police or some other authority figure, he has been forced to run for cover, which is why he is now hiding here, behind this building.

That this outlandishly dressed, 70-foot-tall figure is not hiding at all, but is in fact one of the first things that any visitor to Boston who comes through South Station will see upon arrival in the city, is the artists’ punchline—street art, they seem to be saying, no longer needs to hide. The brothers are no longer members of a marginalized subculture, but larger-than-life fixtures of the international art world, the subjects of major museum exhibitions who are invited to adorn public spaces with their work. Graffiti can now hide in plain sight as the enfant terrible of major public and private collections around the world.

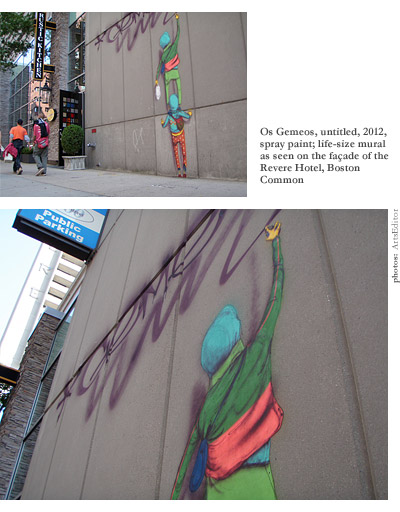

The second, smaller mural, which adorns the side of the Revere Hotel on Stuart Street in Back Bay, reinforces this point. Of all the artworks included in the exhibit, this one is most reminiscent of what one might call “traditional” graffiti—two brightly dressed punks are depicted in the act of tagging the hotel’s façade. One figure steadies himself as the other stands on his shoulder, spray can in hand, in order to apply their tag, “GEMEOS,” in a hard-to-reach—and therefore hard to remove—area. Street art has arrived in Boston and it demands to be seen.

Like all public art, however, these murals have attracted criticism as well as praise since their execution at the beginning of August. As with almost all such installations, the majority of this criticism is focused on the related expense, with some individuals thinking that public art is not an effective use of taxpayer dollars. But some have gone even further, spouting arguments against the murals that border on the absurd. Fox News Boston, for example, recently attempted to stir up controversy on its Facebook page by associating the Dewey Square figure with an Islamic extremist. For Os Gemeos, this hoodlum is an artist, a free spirit, and a friend. He is a recurring character in their art who is typically mischievous, and may oftentimes be up to no good (at least according to standard middle-class mores), but who is always a figure that is upheld as creative and constructive. In post-9/11 America, on the other hand, the depiction of a hooded or masked individual runs the risk of evoking darker, politically-charged fears. Confusion and assumptions about people’s appearances can lead to murky conflations, causing citizens to see threats to their safety around every corner, and this hyper-vigilance can cause us, as a society, to tilt at windmills. Luckily, in this case at least, cooler heads seem to have prevailed and many commentators chimed in to the Fox Facebook “debate” to point out the bigotry, xenophobia, and their act of willfully confusing a mural by a pair of progressive Brazilian artists with the wholly separate and completely unrelated issue of international terrorism. By unintentionally highlighting these undercurrents, Os Gemeos’ murals have at least furthered the public debate in our often circumspect city.

This exhibition is only the most recent in a series of street art presentations at the ICA that demonstrates the museum’s commitment to presenting and contextualizing various aspects of the movement. Shepard Fairey and Swoon have also exhibited there in recent years, and the institution is currently planning a retrospective of Barry McGee. Indeed, street art seems to be everywhere these days—the joint Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles / Brooklyn Museum of Art retrospective Art in the Streets, which just closed at the BMA in July, was a critical and public success. Banksy has become a household name. And Mr. Brainwash, the street artist who was also the subject of Banksy’s 2010 documentary/mockumentary Exit Through the Gift Shop, opened his first solo exhibit in London on August 5th. In case all of that isn’t enough, Doyle New York will launch its first dedicated street art auction on October 16th. Although such sales have been held in Europe for a number of years, the inauguration of such a specialized sale in New York speaks to the current market power of this inherently graphic, punchy, and vibrant offshoot of contemporary art, especially amongst younger collectors.

Although the work of titans from the first generation of street art such as Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-88) and Keith Haring (1958-90) has been achieving record prices and receiving critical attention for years now, it is only recently that subsequent generations have begun to attract widespread acclaim. Whether the art and artists of this movement will succeed in maintaining their edge, humor, and aesthetic sensibilities amongst all of this attention remains to be seen. If, however, Os Gemeos’ Boston murals are any indication, it seems that these hoodlums can take the pressure. In successfully transplanting their vibrant, audacious tags to both the gallery walls and the walls of foreign cities, these boys have proven that although they may refuse to ever grow up, they are certainly not lost, and one can still sense the joyful anticipation with which they make each mark.