Enrico is Italian for Henry. Hence, Luigi Pirandello’s Enrico IV, staged at the American Repertory Theatre during December, begins with a theatrical joke as an actor wanders onto the sparse stage dressed and primed to play one of the minor roles in Shakespeare’s Henry IV. He is dismayed to learn from the three actors already there that this Henry IV is not the 15th Century king of England, but rather the 11th Century Holy Roman Emperor. The new arrival is to play “Bertoldo,” one of Enrico’s vassals, and he is instructed to go away and read the script—an actor being a puppet waiting to have his strings thus manipulated by a dramatist. Bertoldo, though, is rather perturbed by the whole situation, commenting: “if I had wanted to associate with weirdoes, I would have joined the legitimate theatre.”

But just as the drama appears in danger of disappearing up its own backside in a painfully self-conscious and paradoxical (because scripted) deconstruction of the dramatic illusion, that illusion is restored—and such subversion of reality, as well as such self-consciousness, turns out to be an emblem of the play as a whole. A rather long-winded scene proceeds to make clear that the actors are after all characters in a theatrical reality. Enrico IV is revealed to be the role an Italian nobleman (whose real name we never learn) chose to play during an “equestrian pageant” involving fellow nobles (whose effeteness calls to mind the bored, rich partygoers of Fellini’s La Dolce Vita). The pageant ended in tragedy when the nobleman fell from his horse, cracked his head on a stone and, in his ensuing madness, became convinced he really was Enrico IV. A “temporary obsession” became a “permanent reality.” By now, twenty years have passed and Enrico’s house has been transformed into a medieval castle populated with the actors we have just met, hired by Enrico’s late sister to pander to his delusions. That sister also insisted on her deathbed that a doctor be sent for to try to restore Enrico’s sanity, and her son, Carlo, has now fulfilled that request, also inviting along Enrico’s former mistress, Matilde, her daughter, Frida, and her current lover, Belcredi, as the doctor’s consultants. Matilde and Belcredi, we learn, also took part in the ill-fated pageant, the former in the role of Enrico IV’s arch enemy, the Marchesa di Toscana: a role immortalized in the statues of themselves the pair had made at the time and which now hang ominously above the stage, part of Enrico’s throne room.

The nobles and doctor then put on historical costumes over their rather sinister black evening clothes and are introduced to the madman. Enrico, as the doctor predicted, seems instantly to associate them with characters in the historical drama in which he is imprisoned—the drama in which he is forever twenty-six years old, forever at loggerheads with Pope Gregory VII, who is threatening to excommunicate him if he goes through with his plan to divorce his wife. His cryptic, self-obsessed ravings and wild white hair call to mind another Shakespearean king—Lear—at the height of his madness. Yet the barbed sense which some of his remarks seem to make resemble more the feigned madness of Hamlet. Matilde is convinced that he recognizes her and feels her loss greatly. The doctor and Belcredi, by contrast, see only a lunatic with “a mask glued to his face,” as impervious to reality and as frozen in time as the statues themselves.

We now learn of the doctor’s scheme to shock Enrico out of his madness by confronting him first with Frida, who bears a striking resemblance to her mother, dressed up as the Marchesa di Toscana, and then with Matilde, identically attired in green-black clothes meant to mimic the metal of the statues. This vision of the statue suddenly aging twenty years before his eyes is supposed to jerk Enrico’s sense of time into motion again. And though Frida is reluctant, Matilde is anxious to try the scheme; Enrico may always have been a strange character, alienated (according to Belcredi) from his own emotions by his excessive self-consciousness, but she feels guilty about having rejected and laughed at him during the pageant. She welcomes the opportunity to make some sort of amends, despite Belcredi’s apparent jealousy.

Yet after a scene in which the nobles’ 11th Century characters take their leave of Enrico to clear the way for the shock therapy, Enrico reveals to his initially disbelieving vassals that he is perfectly sane (and proves it by succinctly defining Matilde as a “tramp,” Belcredi as a “lech,” and the doctor as a “quack”). It transpires that his senses returned eight years previously, at which point he decided to continue to live as Enrico IV rather than return to 20th Century reality. His motives for doing so are complex. The initial one he expresses is one of malicious pleasure at making people behave like nervous fools in front of him. But then the trauma of his rejection by Matilde comes to the surface. He expresses distaste for a reality in which he would forever be a “beggar at her door,” never permitted inside, and states his preference for the refuge of a reality fixed by history and stuck in time: a refuge from which, at least for the duration of their visit, he can thus manipulate Matilde and her new lover like puppets.

Yet Enrico goes on to claim that his historical masquerade is not, as the vassals suggest, a farce, but rather an existence as good as any other, so long as they “play it as if it were real.” The vassals, though, are not convinced, and they pass on their discovery to the nobles who nevertheless decide to go through with the shock therapy to observe Enrico’s reaction for themselves. That reaction consists of an apparent passion for Frida, followed by a torrent of vitriol about Matilde and what she had become, consorting with the man who, he implies, precipitated the accident at the pageant by pricking his horse from behind (and thus eliminating a rival).

He has maintained his historical identity, Enrico now declares, in a perverse attempt to revenge himself on the stone that hit his head—or, rather, on time itself, that cheated him of his youth by continuing to pass while he was lost in his madness. Moreover, it is not him but they who are mad, forever “playing the roles of the people they think they are” in the outside world. The play ends in the traditional manner of a Shakespearean tragedy—with a stabbing. However, it is not the “hero,” Enrico, who dies, but rather the “bad guy,” Belcredi, slain by Enrico ostensibly for repeatedly insisting that he, Enrico, is not mad. We are left wondering, as the curtain falls, whether the murder was motivated by Enrico’s desire to revenge himself on Belcredi for his part in the accident, or whether, instead, it was a conscious attempt to restore the indulgent illusion of his madness. Either way, it is clear now that he will remain Enrico IV for the rest of his life.

One is also left wondering whether Pirandello intended the play as a philosophical statement or a character study. Are Enrico’s claims that the outside world is mad to be taken seriously or not? The fact that the play was written in 1922, soon after World War I, suggests the affirmative: Pirandello would certainly not be the only artist to have responded to the war’s senseless slaughter with such a conviction. But if this is the case then it seems to me, September 11 notwithstanding, that it can only be viewed by a modern audience with a pinch of historical salt. It can only maintain contemporary life as a depiction of the disintegration of an excessively self-conscious, faint-hearted, and ill-fated man—a sort of modern Hamlet who escapes from grief, existential angst, and self-alienation by feigning madness, and who, moreover, sees nothing degrading or farcical in such a condition since all possible states of existence, for him, would involve playing one role or another. Even so, it is hardly credible that Enrico (not to mention his fellow actors) could keep up such a wearisome pretence hour after hour, day after day, for eight whole years. And for that reason I couldn’t help seeing Enrico’s character (and therefore the drama as a whole) as a mere vehicle for—or puppet of—Pirandello’s philosophy. The strings of the dramatist are, after all, too visible on stage. And for that reason the play rather lacked emotional impact for me.

However, it did not lack dramatic impact. On the contrary, the A.R.T’s production amounted to a memorable theatrical experience. Robert Brustein, in his last of twenty-three seasons as artistic director, created an impressively intense, eerie atmosphere with the help of evocative lighting, music, and occasional dry ice. That atmosphere, uncompromised by any breaks or intervals, builds up steadily to a crescendo in the final act, which begins with a terrified Frida and Carlo being raised up in the statues’ cages, and ends with the nobles disappearing into the stage (from where they emerged at the beginning of the play, symbolizing their entrance into Enrico’s world of make-believe), yelling hysterically that Enrico is mad after all.

I was also impressed by the huge, darkly metallic monolith (serving as the wall of Enrico’s throne room), planted in a stylish diagonal across the stage, perhaps representing the apparently insurmountable, prison-wall-like barrier between Enrico and reality—or, rather, between Enrico and everyday life. The excessive, almost clown-like makeup of the nobles also seemed appropriate, emphasizing the unreality and theatricality of their milieu (which, by the time the play was written, was an anachronism in Italy). The jeans which Enrico wore under his medieval robes, symbolizing his secret reunion with sanity and modernity, were an additional clever touch. And the mirror in the wings, into which Enrico’s old servant, Giovanni, spent most of the play staring, was a striking, if rather obvious, emblem both of Enrico’s self-conscious, self-obsessed madness and of the mirror he holds up to those around him.

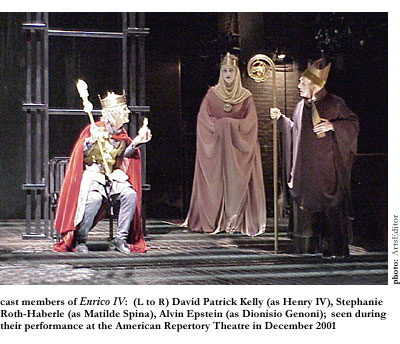

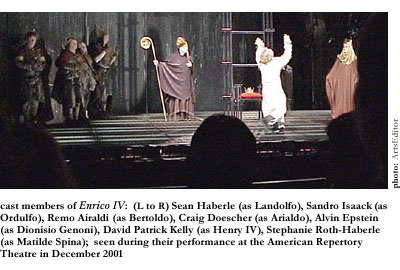

I was slightly less enamoured of Karin Coonrod’s directing. The stagy acting may have echoed Enrico’s claim that everyone plays a part even in normal life, but it hardly encouraged the audience to believe in the psychological reality of the protagonists. Enrico’s histrionics, I thought, were slightly overplayed by a hyperactive David Patrick Kelly, particularly once his sanity was acknowledged and he was no longer pretending to be the Holy Roman Emperor. Stephanie Roth-Haberle’s Matilde, by contrast, though admittedly mysterious, seemed rather lifeless, scarcely credible as the object of Enrico’s youthful passion. Admittedly that is partly due to the fact that her part was so underwritten by Pirandello, but it didn’t help that Roth-Haberle seemed young enough to be Kelly’s daughter. Meanwhile Alvin Epstein rather over-emphasized the doctor’s foolishness, at the expense of his arrogance. Stephen Rowe was more convincing as the sardonic, supercilious Belcredi, but for me it was Remo Airaldi’s Bertoldo who stole the show. Not only was it hilarious to glance aside now and then from the action to see him cowering against the wall in perpetual open-mouthed perplexity and disbelief. It was also the only reaction to anything that happens in Pirandello’s “masterpiece” with which I found myself completely able to identify.