When I abandoned the study of architecture at university, it was because I felt I did not possess the brain of an architect. I did not think in images so much as words and concepts. Moreover, it was these that really inspired me: I found myself hurrying out of the design studio with a sigh of relief when it was time for the philosophy lectures I was required to attend for my minor. Predictably, the buildings I designed were highly conceptual, inspired by such things as Hegelian dialectic rather than such mundane, obvious architectural founts as site, users’ needs, and Frank Lloyd Wright. Equally predictably, my buildings were second rate—their floorplans strained to adhere to the concept, their elevations alien to the site. I looked at the top students and noticed that they eschewed such conceptual methods of design, relying instead on their architectural intuitions: their feelings for space and boundary, form and function, shadow and light. A philosopher, I reflected, doesn’t base his theories on architectural concerns; why should an architect base his designs on philosophical concerns? Philosophy and architecture are two different intellectual worlds, and my name was registered in the wrong one.

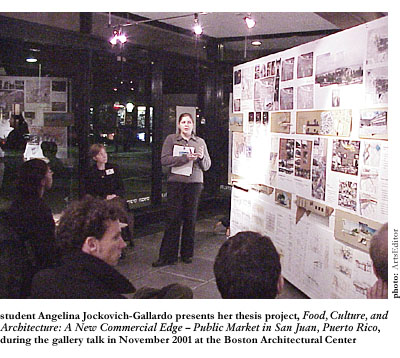

Imagine my surprise, then, when I walked into the Boston Architectural Center’s thesis presentation show in November to hear student after student describe how they had begun their year-long projects—the culmination of their architectural training—by intellectual investigation into a variety of non-architectural fields, and had then striven to apply the results of their research to the design of a building. Not that their buildings were as awkward as mine had been. On the contrary, I am happy to report the show was generally quite impressive to my semi-educated eyes. Nevertheless, I left the talks—which were devoted almost exclusively to explanations of the design concepts rather than of the buildings themselves—with the feeling that the success of the students’ architecture was due not so much to the input of those concepts to the design process as to the ability of the students to dissolve their theoretical concerns into traditionally architectural ones.

Take Corey MacPherson, for example, and his design for an artisan work/dwelling and commuter rail station for Waltham. He started out with an architect’s concern for the flexibility which the spaces within the building would need as their uses changed with each coming artist. But then he presented chaos mathematics as the solution to that problem, on the grounds that chaos theory sees order in what appears to be complete disorder: a situation allegedly comparable to the (physical?) order a building imposes on the changing, disordered lives of its residents. As he puts it in his accompanying essay, “How can we bring order and stability into a disorderly society while still trying to achieve the goals of flexibility? Through chaos.” Chaos theory also states that things look different the closer one looks at them: a factor, again, which is also true of a building.

But this strikes me, at best, as a distinctly strained parallel between the needs of MacPherson’s artisans and mathematical theory. His solution to the problem of adaptable space—viz. sliding panels—seems to have been inspired by architectural precedent rather than fractal geometry or ruminations regarding self-similarity. Nor did his other major design decisions seem to be informed by chaos theory so much as by the realities of the site such as the river, railway line, and people density. Yet that, I suspect, is why his building is a good one. In the end, his theoretical concerns did not impose any limits on his architectural sense because they did not actually inform his design.

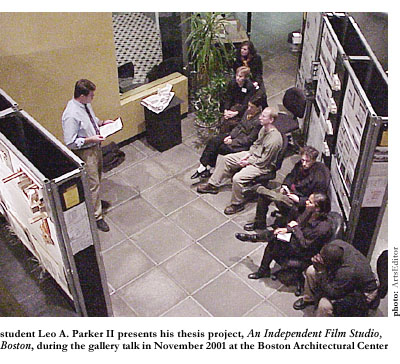

One could say similar things about Leo A. Parker II, with his independent film studio for Boston’s South End. He at least chose an area of intellectual study—film—that has some things in common with architecture: namely, its concern to arrange and frame spaces. But the highlighting of these parallels was as far as his investigation went. As with Corey MacPherson, the big design decisions he took were informed by the nature of the site: for example, the “closed” regularity of Back Bay, broken by the “open,” diagonal slash of Tremont Street. Admittedly the two-aspected nature of his building—with one elevation regular, the other very irregular—was also supposed to reflect the dichotomy between the “closed” world of fictional film versus the “open” nature of the documentary. But, once again, the parallels seem dubious: the concepts of “open” and “closed” seem extremely strained here. But better to let the concepts take the strain rather than, as I was wont to, the architecture. This is why Parker’s building is also a good piece of architecture.

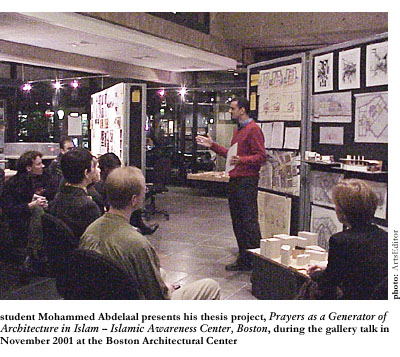

Mohammed Abdelaal, with his design for an Islamic Awareness Center for Boston, was the most successful at boiling his theoretical concerns away. He began his research by considering how Islam should inform architecture in a more intimate, organic way than simply serving as a paradigmatic historical style. This initially led him down various abstruse alleys of inquiry but, in the end, he contented himself with a parallel between the “fixed and flexible” aspect of praying and the fixed and flexible requirements of an architect’s design brief. This, together with his conviction that Islam requires a building to be professionally competent, left him free to let his architectural imagination take over completely. And, hence, he arguably came up with the most successful piece of architecture, with its great semi-circular sweep of a façade punctured, punctuated by a rhythm of beam endings.

By contrast, the only student whose design seemed to have been genuinely informed by his theoretical investigations came up with what was, to my mind, the least successful building. As a preliminary to his design of a public library for Central Square, Cambridge, Jeremy Schwartz engaged in a wide-ranging study of philosophical theories of the self. But his division of human learning into five distinct categories according to their relation to the self (creating a “hierarchy of self-awareness”) inspired an overly-complex floorplan consisting of five disparate elements colliding at “communication nodes” (mirroring his philosophical conviction that a self is a “node in the matrix of communication”). Worse, the criteria for assigning each subject to one of the five categories seems utterly opaque and one can imagine wasting a lot of time looking for the architecture section unless one had some sort of map—much as one would leaf aimlessly through Roget’s thesaurus, trying to place the word one wants in the right category, were it not for the alphabetical index (apparently an afterthought). Perhaps, though, this is the point, for Schwartz believes that “an architecture conscious of this understanding of the self should encourage the random wandering of bodies and ideas.” I doubt the book-readers of Cambridge would agree.

Schwartz’s building represents what I take to be a great sin in design (and one which I found myself constantly committing): that of declining to respond honestly and professionally to the needs of one’s client and the realities of one’s site in favor of building a monument to one’s own (for want of a better phrase) intellectual pretensions. Meanwhile, the other buildings I have mentioned seemed to have come about by needlessly tortuous routes, the intellectual inquiry that supposedly inspired them actually turning out to be entirely redundant. Or worse: a burden that the students had to surreptitiously dismantle, like an existing structure on their site, before they could set their architectural imaginations to work.

I say a burden because I learned later that this method of design is a requisite of the BAC thesis project. This raises the question of whether it is meant to serve as a paragon of architectural practice or whether it is intended merely as an educational exercise. Bob Augustine, the thesis program director, neglected to address this matter when I e-mailed him, but he hinted at the former view when he declared that the recent attack on the World Trade Center (with the ironic shadow it casts on Abdelaal’s Islamic Awareness Center) proves that architecture “really, really matters.” According to Augustine, the WTC was singled out for attack because of what its architecture stands for: namely, an open, free, and tolerant society. “We begin to understand the significance of this art and craft we call architecture when we see the tremendous economic, political, historic, psychological, and spiritual effect the loss of those buildings and their occupants has had on our lives.” In other words, a building, for Augustine, can constitute a highly powerful statement of a society’s values—and, by implication, an architect should strive to make such a statement: to build with what Augustine calls “meaning.”

But he should be careful not to overstate the case. Surely one salient reason that tall skyscrapers were attacked is that they were full of people (thereby maximizing the body count); another is that they were accessible to hijacked aircraft. Moreover, surely the distinctive architecture of skyscrapers has only come to symbolize American values (which, remember, the terrorists interpreted as an unholy obsession with money) by virtue of growing up, as it were, in America. There seems nothing intrinsically democratic about steel and glass: the “modern aesthetic,” of which “modern skyscrapers are the very embodiment.” If skyscrapers had been developed in the Soviet Union, would they not have come to symbolize the state towering over the individual?

Perhaps it is going too far to say that only its use or its spatial location gives a building its meaning, its symbolism. A choice of traditional materials and low elevations, for example, can hardly fail to suggest a certain conservatism, a certain timidity before the outside world, the future. But why try to impose deeper significance on buildings? Why not appreciate them for their sheer architecture—the dazzle of their forms, the richness of their volumes, the wonder of their lighting—the things that are so hard to put into words? (Not to mention more practical criteria such as the ingenuity and efficiency of their use of available space.) Why should a passer-by be required to read a book on cultural, mathematical, or philosophical theory before he or she can fully appreciate a particular building? Owing to the emphatically public nature of architecture, such a requirement seems even less excusable than the case of the many conceptual artists who require their viewers to read an accompanying essay to understand a particular object in a gallery.

On the other hand, it might be argued that such intellectualizing is just harmless fun as long as it doesn’t actually detract from the design process, as in Jeremy Schwartz’s case. After all, there is no reason why a building, like a novel, can’t be appreciated on several different levels, from that of the architectural critic to that of the building site worker. But one still balks at the folly, the sheer waste of time of trying to make completely alien disciplines bear on architecture. After all, how could a building’s design be informed by such a thing as chaos theory? What was the point of Corey MacPherson’s months of laboring over, as he put it, re-inventing the wheel? It seems to me that an architect should not go methodically looking for influences from outside architecture. He should merely be culturally aware and, wherever he feels that culture bearing on a particular design brief, he should respond accordingly. To use a Hegelianism which Schwartz would no doubt recognize, the practice of design should be the antithesis of the overly theoretical BAC thesis method. It should begin and end with traditional architectural concerns. And if an architect is not happy with that, he is always welcome to borrow my philosophy course notes.