When commending an artist for bravery, the conversation typically privileges content over physical adversity. Be it a photographer risking political exile or a pop star releasing a protest album, critical dialogue often relies on right-angled philosophical praxes for its scaffolding. Such a precedent makes it tricky to pitch portraits of friends as acts of resistance, even in the case of a painter as undeniably courageous as Jon Imber, who died on April 17th at age 63 from a disease that defined and transformed his final years of art practice. Regardless, his current retrospective at Danforth Art in Framingham, MA, on view through May 18th (opened March 9th) and epically titled Jon Imber: Carry On, it behooves any writer with half a conscience to do just that.

Diagnosed with ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), a ruthless, degenerative condition better known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, in the fall of 2012, the neo-expressionist parlayed his rapid medical decline into a triumphant resurgence, producing vibrant new artwork at a pace intimidating to any creative professional, much less one who could no longer grasp a paintbrush in either hand. The man possessed a superhuman will, without a doubt, and this contemplative exhibition doesn’t merely track the progression of a vast and varied career. Instead, it populates the viewer’s imagination with an audience of silent muses, some mocking the inevitable, others wincing at nature’s indiscriminate betrayal. By that token, it is vital to approach the newer works free from any euphemistic pretext. These are not celebrations or epitaphs. These are paintings. They transcend the borders of the flesh they render. That they exist at all may be impressive, but their empathic genius bears in each flourish a quality too rare to ignore: bravery, of course.

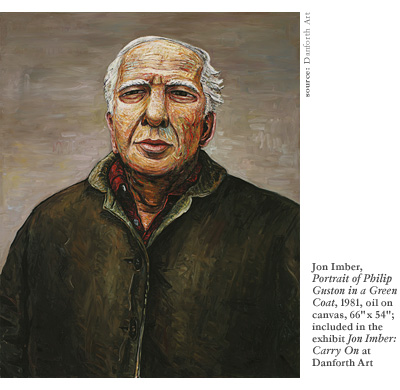

Imber appeared on the New England art scene in the late 1970s with vast, volumetric paintings that fused New School humanism with the unsettling whimsy of Philip Guston, his mentor at Boston University’s MFA program. Over the past three years, his pieces abandoned this language for brash, experimental gestures that burst forth from their supports with boundless urgency, testifying to the unknowable impulse responsible for steering a spirit to greatness. Three dark canvases of formidable size greet the visitor upon entry to Danforth Art’s main gallery, depicting, in order, the artist’s dad (Portrait of Harold Imber, 1982), himself (Self-Portrait, 1984), and his mentor (Portrait of Philip Guston in a Green Coat, 1981)—quite literally the Father, Son, and, perhaps, if we’re being cheeky, the Holy Spirit. This unlikely trinity was created more than thirty years ago, and it shows. Hints of Guston’s bulky, measured touch further dull his subjects’ jaded gazes, while Imber’s furtive, loaded brushwork recalls the self-satirizing color density associated with renegades like Chuck Close and Robert Storr. Still, Imber’s reverence for the classical seems largely un-ironic in this series. He utilized a neo-impressionist’s relational faculty to establish an unexpectedly harmonious palette, just the sort of vibration peculiar to his oeuvre. Danforth’s executive director and Carry On curator Katherine French noted that these “monumental portrait heads… seem to be universally attractive to museum visitors. I personally regard them as central to the exhibition.”

Indeed, pieces like the plaintive Morning Paper (1981) maintain this tonal standard—the environment of the canvas establishes its own stylistic criteria for figurative representation by glimpsing through cracks at a world askew. (As it happens, Imber’s favorite piece in the exhibit is a smaller, arrestingly intimate study for Morning Paper executed a year prior.) Disembodied hands hold a baby with far too many teeth in mid-air in Memory (1992), a grinning adolescent son rides his long-torsoed centaur dad in Father and Son (1979), and the Virgin Mary cradles a baby Jesus in pink footy-pajamas in the nook of her arm in Madonna and Child (1989). The surrealism might translate as playful if not for Imber’s deliberate hand and expert attention to weight and shadow. Guston’s penchant for sending up cultural symbology clearly rubbed off on his protégé, but it’s the painting hanging to the right of the opening triad that truly codifies Imber’s individual mission as a storyteller.

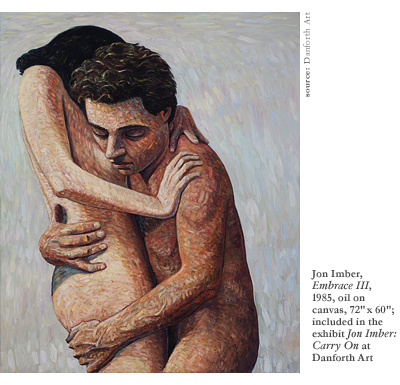

In Embrace III (1985), a naked couple grasps each other with such organic awkwardness it’s difficult to tell if the woman is resisting or re-adjusting. If it wasn’t already obvious why Imber was tenured at Harvard University as a figure painting professor for 27 years, the deliciously inky blue cast shadow cleaving their rib cages illuminates his mastery in no uncertain terms. Artists concerned with the nude are generally drawn first and foremost to the translucency of flesh—ample opportunity lies therein to explore the most sensual aspects of oil media and show some technical skill in the process. Jon Imber, however, had a different agenda. The focus isn’t texture, but mass. Controlled hoards of color swarm together in thick, sculptural swells, forgoing specificity for the universal, a stylistic slant inherited from legends like Gauguin and Cézanne. Imber described this through-line between the older and newer aesthetic as “spiraling energy”. As that lexicon applies to figure painting, the results often skew eerie, or at least impersonal, but there’s too much tenderness in Imber’s baby blue highlights and Bernini-esque contact points to assume any post-structural detachment on his part.

The retrospective’s titular pun (“carry on” both references Imber’s fascination with interpersonal transport as a physical manifestation of the care/burden dichotomy and his incentive for making art as his health disintegrated) casts a particularly strained light upon Embrace III. The couple can’t quite get in sync—the female figure pushes against her partner’s shoulders as he crouches down to secure his placement. The man might be planning to flip the woman over his back, a la Carry (1985), the large painting to the right. While his positioning doesn’t necessarily read as predatory, the two subjects still aren’t communicating. His facial expression betrays little of the concern or desire one might expect, and hers is inscrutable, hidden from the viewer behind a mop of tousled black hair. It’s tempting to chalk that decision up to the usual “headless nude” trope endemic to Western tradition, but the pressure of her hand on his chest instills her presence with a certain precarious agency, a flinch away from the rest of her body’s surrender. The couple inhabits a crackling pale pink womb that serves to underscore the piece’s elemental outlook. Embrace III honestly captures the vulnerable, cloying weirdness of falling in love, and, by extension, quickens the retrospective’s pulse.

Approaching the recent artworks hanging somewhat unceremoniously in the hallway outside the main gallery feels sobering, to say the least. It’s difficult to divorce oneself from photos of Imber bracing a brush between the backs of his atrophied hands as he sways above a panel, and it’s equally difficult to let his objects speak when interview sound bytes about “living the painting” and “mistakes” as “new challenges” hum low in a psychic soundtrack. Richard Kane’s new film Jon Imber’s Left Hand, which screened at the Independent Film Festival Boston, further disseminates the staggering specifics of his determination into popular lore. Many articles prodding Imber for details on how exactly he manages surfaced in the last few months, and the answers seem simple—his wife, Jill Hoy, and a studio assistant, Holley Mead, prepared his supports, lifted him from his chair, and delivered him to his work station. These faces comprised his world—the people who brought him meals and told him stories as his body bowed all too quickly to the will of time.

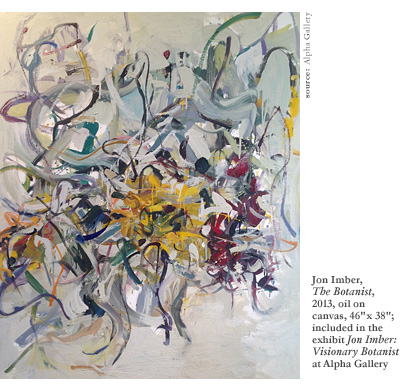

These paintings might derive their style from coping—the wieldy scale, the risky gesture, the reverent iconization of the sitter—but their visual import remains spectacularly unmatched. Imber’s preternatural sense of shade value rushes to the forefront of each composition. Brushstrokes cohere their energetic dance into stunningly nuanced plein-air observations, and pieces like the effusively streaky George (2013) or the lithographical Beverly (2013) defy neurological expectation with pluck to spare. Much critical fuss has been made of Imber’s increasing lack of technical precision this past year, but most modernists will attest that facility doesn’t originate from an artist’s hand, but an artist’s eye. While that distinction may not have been immediately apparent in his expressionist, botanical fare on view at Alpha Gallery (in the exhibit Jon Imber: Visionary Botanist, which ended on April 2nd), the selections at the Chandler Gallery at Maud Morgan Arts (in the exhibit Jon Imber: Painting up a Storm, which ended on March 21st) and at Danforth Art brim with unremitting, joyful dexterity in vision, if not execution. ALS may have ebbed his fine-motor regulation, but his capacity for economic, intuitive decision-making, or, in his words, “painting against the mark”, blooms into electrifying resonance throughout this cluster of acquaintances.

The static symbolism of his formative years made way for a close, furious touch, helping to enliven expertly balanced flurries of mustard and terra cotta like Aparna (2014) and Sebastian (2014). Imber reported in an interview by e-mail on April 1st: “98 out of 100 of the new portraits were done in one session. Both in Stonington, Maine and in Somerville, I had my sitters sit in the same chair with a light and dark side. My focus was on the face, so I kept the other variables to a minimum.” Imber’s practice resembled laboratory science, complete with controls, procedures, and unforeseeable outcomes. That alchemic attitude whirs and titters down the hallway at Danforth Art, summoning viewers to invent their own conversational fragments and interior monologues for the abiding coterie of friends and family.

Late last year, Imber declared that “good painting is never planned”. These lively pthalo dollops and buoyant sprays of oil over wood prove nothing less. Good painting, on the contrary, manifests in deviation, in the not-quite-there-yet. Assembly obfuscates subtler, more secretive slights-of-hand the viewer only recognizes after the act of seeing turns as urgent as an inhale. Jon Imber’s artworks have always clawed the corners of reality’s dimensions, and his artistic truth gestates not in the overt, but the flicks, drips, and impasto that personify each piece. Carry On preserves the legacy of a man with a precious gift and indomitable heart. Despite seemingly insurmountable odds, Imber’s brilliance refused to splinter under the unimaginable weight of his illness, and it is our privilege to witness that valor in action.