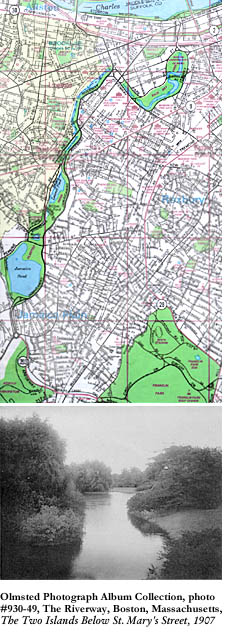

Back in the late ’70s—the late 1870s—when the city fathers of Boston took Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903) up on his bid to design a long and sinuous system of linked city parks in the “picturesque landscape” style, they must have been thinking ahead. They must have known that if Olmsted could do for Boston’s public lands what he’d already done for Manhattan’s Central and Brooklyn’s Prospect Parks, then Boston would be that much more livable than it already was. So they let him have his way with that string of puddingstoned hills, ponds, brooks, and marshes that extends for several miles from Franklin Park, Arnold Arboretum, and Jamaica Pond in the Dorchester-Jamaica Plain neck of the woods, along the Muddy River and through the Fens to its mouth at the Charles. And Olmsted, the first and still the foremost landscape architect in the United States, went forth and made them a necklace. An emerald necklace.

True, those city fathers couldn’t have anticipated that a century later the Fens would be known as much for the pick-up basketball games played by parolees from Park Drive’s pre-release center near the rose garden as it would be for the gay cruising scene near the Victory Gardens. They never could have guessed that Franklin Park would recover from its busing-era reputation for daylight muggings, body-dumpings, and car-burnings and attract large crowds from the most densely populated and least touristy Boston streets to its gospel music, Caribbean culture, and kite-flying festivals. It would have been very hard for them to imagine the inter-racial couple on the Jamaica Pond path strolling their coffee-skinned kid past the punked-out lesbian couple cuddling on the grassy if goose-besoiled shore on a recent Sunday afternoon; the slick of heating oil making rainbow patterns on the surface of the Muddy River a few years back after a delivery man stuck his nozzle in the wrong pipe outside of a Longwood-area apartment building; or the biologist in hip-waders and surgical gloves standing in the Muddy and holding up to the Cambridge artist on her way home from her ceramics studio in Jamaica Plain a waterlogged jacket and plastic Coke bottle he’d dredged from the bottom, explaining that he was here to test the waters for the West Nile virus.

True, those city fathers couldn’t have anticipated that a century later the Fens would be known as much for the pick-up basketball games played by parolees from Park Drive’s pre-release center near the rose garden as it would be for the gay cruising scene near the Victory Gardens. They never could have guessed that Franklin Park would recover from its busing-era reputation for daylight muggings, body-dumpings, and car-burnings and attract large crowds from the most densely populated and least touristy Boston streets to its gospel music, Caribbean culture, and kite-flying festivals. It would have been very hard for them to imagine the inter-racial couple on the Jamaica Pond path strolling their coffee-skinned kid past the punked-out lesbian couple cuddling on the grassy if goose-besoiled shore on a recent Sunday afternoon; the slick of heating oil making rainbow patterns on the surface of the Muddy River a few years back after a delivery man stuck his nozzle in the wrong pipe outside of a Longwood-area apartment building; or the biologist in hip-waders and surgical gloves standing in the Muddy and holding up to the Cambridge artist on her way home from her ceramics studio in Jamaica Plain a waterlogged jacket and plastic Coke bottle he’d dredged from the bottom, explaining that he was here to test the waters for the West Nile virus.

That those cardboard-collared, starch-shirted, Brahmin bureaucrats who ran the town had the sense, in class-conscious Boston, to hire a democratic visionary who actually called his parks “people’s gardens”—a term that sounds like it comes from Berkeley in the 1960s—suggests that they were not as blind to the needs of the increasingly multicultural masses as we might blithely assume. For Olmsted wanted the Emerald Necklace, like all of his public parks, to be for the healthy, therapeutic, and contemplative leisure activities of everyone who lived in the city, regardless of color, creed, or credit history—for walking and wondering and using all five senses to take in with a Wordsworthian sensibility the woods, waters, and meadows.

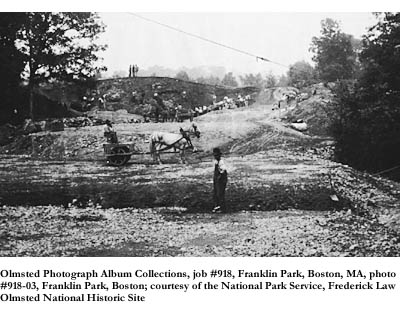

Olmsted designed his parks strictly for “passive recreation,” says Mark Swartz, National Park Service ranger at Fairsted, the Brookline house where the landscape architect lived during most of the 20-year beading of the Emerald Necklace. Taking his cue from an 1850s visit to a park in Liverpool, England, that had been modeled after the sheep-meadowed English countryside, Olmsted had collaborated with Calvert Vaux on his first big project—the 800-acre Central Park—with the high-minded Romantic and Impressionist intentions he kept to the end. He intended the big tracts of urban land he talked cities into preserving for public use to be serene wilderness retreats from the noisy, dirty streets. Planned wildernesses, yes. Wildernesses created from scratch by teams of surveyors, photographers, engineers, draftsmen, masons, and horse-drawn carts. Wildernesses carved out of civilization rather than the other way around—the garden in the machine rather than the machine in the garden—and designed in what Swartz likes to call a “plant by number” horticultural style that contrasted, in its artificially organic arrangements, from the royalist, symmetrical landscape architecture of Paris. But a wilderness nonetheless.

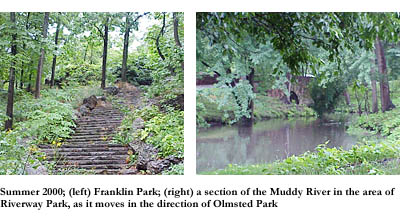

To make the daydreams of the masses who would walk one day in his parks come true, Olmsted gave them wondrous views, prospects of distant, hazy hills from the puddingstone promontories like those in the secluded recesses of Franklin Park. Rather than flat, ornamental, gravel-floored gardens of trellised roses, rigidly rowed tulips, and linden trees with square crowns, Olmsted gave them a condensed version of the countryside they no longer had access to in the graying gloom of the city. Reversing the adage and letting nature intervene in man, he gave the industrialized citizens atmospheric glens of dark-green-needled hemlocks like those along the brook at the foot of Bussey Hill in the Arnold Arboretum, and copses of elephant-skinned beeches like the ones on the south slope of the hill across the brook—beeches with trunks now as big around as the circumference formed by the arms of the hand-linking, tree-hugging lovers who shouldn’t have scratched their initials there. He gave them hillside clusters of alder, lilac, and mountain laurel as indigenous to New England as beech and hemlock and as subtly evocative. Yes, he even gave them the path curving around the cluster, the copse, and the glen; and he spaced the clusters, copses, and glens at irregular, unpredictable intervals and blazed the intersecting network of soft meandering footpaths between them, making one footpath scale the hill to the puddingstone prospect, another follow the brook—a brook he’d channeled and banked with rough fieldstones for a faux-antique effect—and made still another wind between a mossy outcropping of puddingstone on the left, say, and a stand of raspy oaks on the right until—surprise—it spilled the walker into the head of a long meadow with a sweeping view of still more clusters, copses, and glens. Not to mention thickets, stands, meadows, hedges, groves, glades, and bowers too.

Natural abundance and innocent surprise—that’s America at its best, and that was an Olmsted park.

Maybe it was early summer in 1897 or so, and the daydreamer was a solitary birdwatcher, a student of anthropology, literature, or philosophy at Harvard, a reader of Keats eager to hear, in lieu of nightingales not indigenous to our continent, a woodthrush fluting in the woods at dusk with “full-throated ease.” Maybe he was a Whitmanesque celebrant of the motley American crowd there to boost his utopian political morale—a young idealist walking within simultaneous sight of an extended African-American family from the back side of Beacon Hill picnicking in a shady meadow and a gang of Irish-American ruffians from South Boston who’d come by streetcar to see the pretty Cambridge girls they’d heard could be seen strolling coyly in the sunshine with their parasols. Maybe he was a she stalking butterflies and violets for her insect and wildflower collections, or a group of women, officemates from a printing firm on the Boston Common, meeting on Saturday at Jamaica Pond to rent a couple of rowboats and picnic on the island. Immigrants who stoked the roaring furnaces and cleaned the elegant offices of public buildings for a living. A sailor-supported prostitute taking a break from work in Scollay Square on a weekday afternoon to get some fresh air. Comically respectable philanthropic bankers and their highly entitled and well-served wives. America could be heard singing in an Olmsted park, in Boston as well as in Brooklyn.

In the 1920s, says Swartz, tastes in American parks changed. Olmsted had already made his mark for good, dying at the turn of the 20th Century after doing for Seattle, Chicago, Louisville, Washington, D.C., and other cities what he’d done for Boston and New York, meanwhile siring a pair of sons who’d continue his work until the 1950s. His parks couldn’t be destroyed, but they could be modified. At the mouth of the Muddy near Kenmore Square, massive road construction (Park Drive, the Mass Pike, and Storrow Drive) obscured some elegant stone wall and bridge work and sent the river underground for several hundred feet, only to emerge in the shadow of overpasses as a kind of public urinal. A golf course, stadium, and zoo filled the pastoral Franklin Park meadows that had been designed with tender bleating lambs and their lyrical shepherds in mind. The copses and thickets and glens remained, but now they became more full of boisterous and industriously joyful noise than the plaintive and poetic sound of thrushes. The birds fled for the hills. The Blue Hills of Milton, just south of Boston.

Olmsted’s bucolic and atmospheric style was nothing short of revolutionary for his times. It’s hard to imagine our cities without the mark Olmsted left on them, especially given the increasing reluctance of Americans to put their tax dollars toward the common good. A massive effort went into what might appear, in the deceptively simple surface features of an Olmsted park, to be the result of a hands-off, let-it-grow-wild style. This effort and the outlines of the style are abundantly evident in the collection of 150,000 drawings and 60,000 photographs that the National Park Service found—and began immediately to preserve—when Fairsted was turned over to the feds in 1980. It’s especially interesting to see the before-and-after photographs—a piece of the Muddy River in the beginning stages of development and then in 10 years when the planted vegetation had begun to take to the earth-mover’s contours, for example. After that, it’s nice to go outside with the likes of a ranger such as Mark Swartz and get a look at the private grounds Olmsted designed for himself around his rustic cottage. The hemlock in front where wagons and carriages pulled up. Over in a corner of the lot, the puddingstoned knoll of laurel, moss, fern, and wildflower, with a sweet little trench of a path curving through. The densely vegetated hollow to one side of the house, bordered by a rough stone wall. And the sweeping lawn on the other side of the house, with the graceful old elm tree that Olmsted planted in the middle, the insulating edge of bushes up toward the edge of the property, and paths diverging in an inviting manner around the house on one side and up into a woods on the other. At not quite two acres, the Fairsted grounds falls just under an acre short of Olmsted’s notion of “ideal suburban” living. It’s very nice there—you wouldn’t mind having that sun room looking out onto that elm tree, would you?—but then practically the only doubt a person could ever have about Olmsted’s influence comes creeping up from the conscience.

This is an awfully precious piece of private property, isn’t it? What if relatively few people could afford this kind of thing, but enough so that they privatized the formerly rural land up and down the coast and inland all the way to Worcester? What if those people put big fences around their property to keep out the poor, zoned their neighborhoods to be exclusive to all but the upper middle class, had herbicides applied to the lawn on a weekly basis, built extensive additions onto their already huge McMansions, ran energy-draining air-conditioning and central-heating systems all year long, and installed high-tech alarm systems? Would those same people give one damn about helping to keep up the parks in the dark and dangerous cities that they commute to on weekdays and draw their money and energy from?