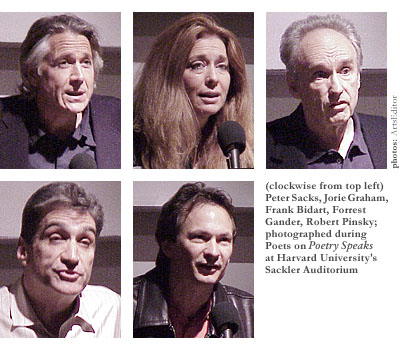

At the November benefit for the Grolier Poetry Book Shop, a polite but eager crowd of young and old poetry enthusiasts gathered in the Sackler Auditorium at Harvard University. They were there to listen to five contemporary writers and scholars deliver impassioned tributes to some of the finest, most fascinating American poets of the past century. Frank Bidart spoke on Robert Lowell; Forrest Gander on Laura (Riding) Jackson; Pulitzer Prize-winner Jorie Graham on Elizabeth Bishop; former Poet Laureate Robert Pinsky on William Carlos Williams; and Peter Sacks on Randall Jarrell. During the course of the evening, each speaker mixed verse with historical and critical commentary to create a comprehensive portrait of a single artist and his or her body of work. An audio recording of one or two of the respective subject’s poems prefaced each speaker’s talk. The audience was also treated to additional electronic recitations by W. B. Yeats, Anne Sexton, and Wallace Stevens.

Taken as a whole, the evening was an engaging look at five captivating figures who were formerly prominent on the American poetry scene. The speakers who occupied the stage were knowledgeable and entertaining in roughly equal measure, and their enthusiastic praise of poetry and these poets was both genuine and deserved. Some excellent poems—both well-known (Lowell’s Skunk Hour, Bishop’s One Art) and more unfamiliar (Jarrell’s 90 North, Williams’ Queen-Anne’s-Lace)—were highlighted, and stood out as compelling testaments to the quality of these poet’s oeuvres. However, while the event was successful in that it was both entertaining and lucrative (it raised over $3,000 for the Grolier), it was marred by several flaws.

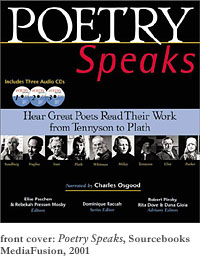

The fundraiser, which was sponsored by the publishing company Sourcebooks MediaFusion, was modeled after Sourcebooks’ acclaimed text Poetry Speaks, a unique anthology by and about poets that couples printed verse with rare, author-recorded poems and critical essays, much in the style of the benefit’s speeches. The format, both of the book and the event, is based on the notion that hearing the voice of a poet reading his or her own poem not only enhances the work by bringing out its sonorous and rhythmic qualities, but that hearing a poem read aloud is the only way to truly experience its essence and to understand the poet’s mentality. To quote Robert Pinsky, “If a poem is written well, it was written with the poet’s voice and for a voice. Reading a poem silently instead of saying a poem is like the difference between staring at a sheet of music and actually humming or playing the music on an instrument.” While it is undoubtedly true that hearing a poem can lead to new insights and enhance the “sound” of the piece, this assertion seems overstated and dubious—more a marketing trick than a truism. The trouble with the premise is, ultimately, that poets are not necessarily good readers, and that having an authentic voice present a piece with a poor interpretation can actually have a detrimental effect in terms of reader comprehension and appreciation. Listening to poets may make our experience of them as poets—as people—fuller, but it does not necessarily reveal or enhance their work as much as one would wish. Despite Pinsky’s belief, there is a lot to be said for words on a page—the chance to look at a poem, to size it up and see how it works, to be able to trace again your favorite parts or to revisit the muddy currents. Listening to a poem always means that you will come to the end. Although you can rewind and begin again, you cannot jump from part to part, or ever really grasp the solid whole.

Still, it is amazing to hear poets’ voices impossibly cross the grave to speak again, it seems like such an intimate communication, a real privilege to hear not just words, but poetry: words and images elevated to art. And there were pleasures to be had in listening that evening. The surprise of the night—that Robert Lowell, despite his Yankee pedigree, had an oddly Southern drawl—was followed by perhaps more predictable but no less gratifying revelations: Anne Sexton’s voice was as strong, brassy, and no-nonsense as her poetry; William Carlos Williams’ tones, on the other hand, were matter-of-fact and plain. Laura (Riding) Jackson, the least well-known of the central group, had a patrician grandeur to her tone that seemed to come straight out of the 19th Century; it’s hard to believe that she was recorded reading her work as a young woman (she gave up poetry in her 30s), or that she was quite so oddly bohemian.

Still, it is amazing to hear poets’ voices impossibly cross the grave to speak again, it seems like such an intimate communication, a real privilege to hear not just words, but poetry: words and images elevated to art. And there were pleasures to be had in listening that evening. The surprise of the night—that Robert Lowell, despite his Yankee pedigree, had an oddly Southern drawl—was followed by perhaps more predictable but no less gratifying revelations: Anne Sexton’s voice was as strong, brassy, and no-nonsense as her poetry; William Carlos Williams’ tones, on the other hand, were matter-of-fact and plain. Laura (Riding) Jackson, the least well-known of the central group, had a patrician grandeur to her tone that seemed to come straight out of the 19th Century; it’s hard to believe that she was recorded reading her work as a young woman (she gave up poetry in her 30s), or that she was quite so oddly bohemian.

Although Pinsky, Graham, and Bidart were all able speakers, I found the sections about Jackson and Randall Jarrell to be the most interesting. Bishop and Lowell are the two heavyweight American poets of the century—both are read and discussed so frequently that any further rehashing of their work seems inevitably to degrade into triumphal re-declarations of their place on the canon’s highest tier. Although their status is definitely deserved, celebrating such poetic fixtures seems a bit old hat. Contrariwise, Williams is frequently lauded, but manages to escape the same trap; it is always a blessing to evade his interminably quoted snippets about plums and red wheelbarrows in favor of some of his more searching and evocative longer poems. But Jackson and Jarrell are truly marginal, and if perhaps they were not quite the poets that the others were, their life stories seem more fascinating simply for being overlooked.

Gander’s take on Jackson (who he described as “very strange and powerful”) was both funny and bizarre; he brought her to life as an enigmatic cult figure. Sacks managed to bring out the true, deep strains of sorrow and solitude in Jarrell (Lowell, a friend of his, referred to him as the most “heartbreaking” poet of his generation) in a way that was not pitying, but deeply humanizing. In recordings, Jarrell sounds dark and slow; his poems, and what Sacks terms his “refusal to be unhaunted,” came as the greatest revelation. Jarrell has long been branded a genius critic but a mediocre poet, forever passed by while Lowell, Bishop, Williams, and their ilk were elevated to near-godly status. This judgment, this dismissal, does not seem quite fair. Not that November night, and not now, when the world seems increasingly as bleak as Jarrell believed. We now live in a country fraught with the looming possibility of war and shadowed by acts of terrorism at home and abroad. Our world seems to be growing inexorably darker, and it is right that some poets should not comfort us, but instead warn us of the abyss.

Ultimately, despite the strengths of their material, I wish that the poets had been a more motley crew. A representative from the avant-garde would at least have been a nice change; or perhaps a member of the Harlem Renaissance; or a newcomer to the States who wrote pieces in English. Still, despite the regularity of the poets included, they formed an interesting whole. They all, to paraphrase Jorie Graham, “[paid] hard attention, and [found] rarely what we would call consolation.” We have a wide range of sorrow here—in Robert Lowell’s long depression and writer’s block; in the terrible solitude of Bishop, first an orphan, then a woman adrift from her home and lover; in the strange, restless dissatisfaction of Jackson. Williams seemed to be the only exception; it is good to have cheer in times of sorrow.

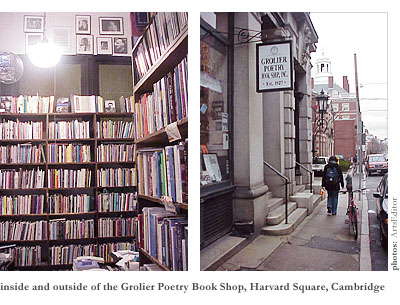

The event also seemed off-focus in that, despite the fact that it was designed to raise money for the Grolier Poetry Book Shop, there was hardly a mention of the store—a real oversight, especially because it could have attracted larger donations. For area poets and poetry lovers, the Grolier is Harvard Square’s most distinguished landmark, both for its longevity and its unique focus. Founded in 1927, the Grolier is the oldest continuously operating poetry bookstore in the United States. Its survival—and success—is quite a feat in this age, when even with the growing popularity of poetry slams and coffeehouse readings, books of verse do not exactly dominate the bestseller lists. Cozily cramped, with texts piled from floor to ceiling and an ancient dog blocking the aisles, the Grolier nonetheless manages to stock over 15,000 volumes—poetry books and manuals, journals, works in translation, criticism, and poesy from every part of the globe. Over the years, the shop has been a favorite haven of such major 20th Century poets as T. S. Eliot, E. E. Cummings, Marianne Moore, Charles Olson, Allen Ginsberg, and Donald Hall. The shop is not important merely for its marketing niche; it serves as a progressive source of support for area poets. In 1979, under the management of current owner Louisa Solano, the store began to branch out in its role as a community resource. The Grolier now sponsors autograph parties, hosts an annual reading series and poetry festival, and funds the Grolier Poetry Prize. Solano herself is one of the store’s main attractions; she is always unfailingly polite, helping customers to find titles and even advising browsers about Master of Fine Arts programs. It seems like the evening would have been more satisfying and indeed compelling if someone had memorialized the store, spoken of the poets who thrived off its nurturing environment, or praised its place in a world where poetry still does not get its just due.

But in the end, what truly bothered me about the event was that it seemed so rooted in the past. Surely we can say more about poetry than that it is good to read it aloud; surely we can do more than revisit and commend previously acknowledged masters of the forms. Although it is always good to remember where we have been—as Jorie Graham put it, “great poems stay strangely relevant”—I wish that this event had said a little bit more about where we are going.

Ultimately, though, does it really matter what the event was lacking? Sourcebooks’ continued sponsorship of the Grolier—not only did it fund this event, but it donates a certain percentage of each copy of Poetry Speaks sold to the store—is commendable, no matter the philosophy behind it. Certainly it is good to fund poetry, to inspire interest in poetry, and to help venues that popularize the love of poetry to thrive. And one can never read too much poetry, or the same poem too many times, or spend too undue time visiting with one poet. Here’s hoping that the Grolier survives to celebrate its 150th birthday, and that in that far-off time, over a hundred people still eagerly venture out of their homes on a chill November night to listen for two hours to poets speak ardently of craftsmen and their lonely craft.