Taking an early lunch break from my job in a publications office at Harvard, I had biked as fast as I could the two or three potholed miles through the back streets of mid- and East Cambridge, somehow not realizing (after more than 20 years in the area) that I could have biked more fluidly along the Charles and gotten to Killian Hall on the MIT campus, in time for the noon performance of Poetry & Motion, a collaboration between poet Sarah Tyler and Kelley Donovan & Dancers.

I had worked up a sweat and was steaming like the cooling tank around the corner at the little nuke on Mass. Ave. In my aisle seat in the tenth or eleventh row, I turned to let the big noisy fan at the back of the hall have its way with me, realized that it was blowing hot air, and turned back in my chair to open my notebook. I wondered if the brown, red, and gold tones of the walls of the small performance hall were the manifestations not of an MIT maintenance crew with paint brushes but of the melodious sounds of Chopin and Beethoven coaxed from the grand piano that napped under cover in a corner of the parquet floor. And I looked around at the readied faces of the small yet sufficient audience.

Some of the spectators in the almost entirely female audience looked young enough to be students—maybe grad-student acquaintances of Kelley Donovan’s in MIT’s world-renowned economics department where she works for professors and administers the Artists Behind the Desk Series of recitals and readings. Some I guessed to be her administrative staff peers—people, who like thousands of us in the Boston area, hold down day jobs in front of computers in academia where progressive thought thrives, the pressure is relatively low, and there’s ample opportunity to enjoy the camaraderie of fellow staff artists and intellectuals. Women in their 30s and 40s, mostly, who majored in dance at Emerson, maybe, in piano performance at New England Conservatory, or in fiction writing at B.U. Midwestern exiles. Transplants from northern New England. Feminist neobohemians who grew up in Lexington. Veterans of the painting program at the Museum School, who’ve stuck around Boston for the cultural action, or for the proximity to New York or the ocean and the mountains—who’ve settled for the benefits and sufficient salaries offered by our local bastions of brainpower (there but for the fortune of the National Science Foundation and the Pentagon), and who’ve kept producing art at night and on weekends.

Then someone turned off the fan (roughly the size of a WWII fighter plane’s propeller), the noisy hot air came to a halt, a smiling public woman stepped forward to introduce the show, and the short performance of dance and poetry began.

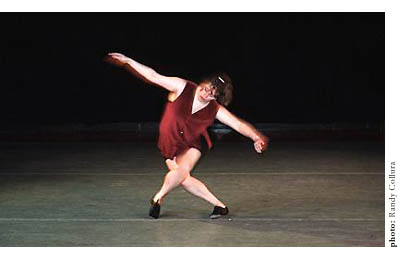

Kelley Donovan is an unusually personable dancer. Muscular, radiant, big-boned, fair-skinned, pleasant, and wholesome, with medium-length straight brown hair and round brown eyes, she isn’t the ropy stereotype of the angst-ridden modernist of passionate jerks and anguished twists. Donovan could be from a dairy farm in Vermont in the 1950s, so milk-white and clear are her limbs and face against the black blackgrounds of most of the costumes she wears. She takes a farm girl’s disarming pleasure in making rounded, rolling moves on the stage, motions suitable, perhaps, for a piece choreographed to the sensual barnyard scene in Tess of the D’Urbervilles among the dairy maids on the farm—or for an improvisational interpretation of one of the Indian paintings at the Sackler Museum at Harvard, with the Hindu pleasure-god Krishna, in transient incarnation as a beautiful blue buck, running from his adoring gopis, the milkmaids who chase him over the hills of Punjab, Kashmir, and Utar Pradesh.

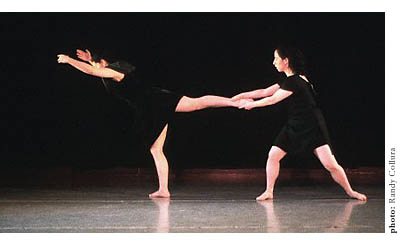

That is not to say that Donovan isn’t suited for the parts suggested by the Rimbaudian, live poetry of Sarah Tyler she and her small troupe danced to for a half-hour that day. In fact, given Tyler’s attention to natural imagery and her repeated cries and pleas for peace and a healthy connection to earthly things, Donovan in her earthy earnestness seems more suited to the task than her busiest troupe member, Rosemary Candelario, whose compact body, cropped black hair, and angular movements bring to mind the determined minimalism associated with Merce Cunningham and company. But even though Donovan seems right enough for the celebratory suggestions of the poetry, it isn’t always clear that she has made the most of the content. The dances could respond more clearly to the particular narratives and metaphors of the poems: more mirroring, miming, supporting, or just plain illustrating.

Likewise, Sarah Tyler can be considered a likely enough poetic complement to Donovan’s dances. She sustains a prolific verbal energy in her poems. She’s at her best when writing to or about another particular person and when developing a single body of imagery. She should therefore be encouraged to keep those love poems coming—even while protecting her right to proclaim, after a particularly stirring epiphany in “Poem for Anna,” that “This isn’t a love poem. I do not write love poems.” Like the open-formed and starry-eyed Beats—who took to heart Walt Whitman’s admonition, “Unscrew the locks from the doors!/Unscrew the doors themselves from their jambs!”—Tyler summons the courage to surrender her imagination to her poems, letting them do what they want to as long as they bring out the best in her. She may have learned this from reading Allen Ginsberg or Diane Wakoski, or from taking to heart the encouragement of some especially hip teacher in the English department of whatever high school she must have graduated from only a year or two ago.

Unpretentious and studious-looking, with an undramatic but clear delivery, Tyler reminds you of kids who come out of the art-happy Cambridge School of Weston—bright and ambitious young women and men whose mothers are professors of anthropology at UMass Boston—the only difference being her apparent modesty about her talents and the fact that she seems to be from Somerville. She knows already to render herself (and readers of her poetry) airborne by concentrating on a central metaphorical image or body of imagery, as in the playful non-love poem “Chess” (which concludes its extended comparison of an interpersonal relationship to the board game with a punny and exclamatory “Mate!”). In the aforementioned erotic “Poem for Anna,” the metaphor is built around the the ardent search of her lover’s “pale slender fingers” for the key to the door at the entrance to the poet’s “inside room.” (Once inside together, it’s nice to hear that they hold each other “not with arms but with words so strong no one could tear us apart.”) And then on the down side there’s the melodramatic “Crucifixion,” featuring her lover weeping blood instead of tears.

Epiphanies appear and disappear in Tyler’s long poems. (Between the epiphanies the train of thought stays on the rails well enough, but not without some jarring bounces.) Her dithyrambic free verses could be called odes and litanies—or diary entries and naive declarations of artistic and spiritual independence. It depends on the epiphanies. Her youthfully unedited disclosure of all sorts of raw feeling—or her expression of raw feelings that may not actually yet be hers but which sound and feel so good to express that she may as well pretend they are—is both her weakness and her strength as a writer. She too readily gives in to the temptation of cliché, and yet manages to do something verbally authentic to the cliché before she lets it go. This is so in the frequently charming and impressively energetic “New York,” where at first one wishes she’d expanded a little on the useful metaphorical possibilities of lines such as these: “Why are your streets so dark under the blue sky?” and “Why are the faces like granite?”—lines which, typed out on the keyboard in privacy, seem to make more original use of the setting than they did when pronounced in public.

For better and for worse, Tyler isn’t afraid to let it all hang out in her poems, even to admit with adolescent brazenness, “I can forget that anyone else exists.”

Poetry and dance are strange bedfellows. Neither quite knows how to turn the other one on. Even poetry of the exclamatory sort is afraid to make too much noise in bed with dance. Dance makes poetry feel like a fuddy-duddy, and poetry makes dance feel like a ditz.

Poetry can certainly work magic when melding rhythm and phrasing—that’s almost what poetry is by definition: where the meaning of a poem is incorporated in its music—but it’s not the kind of magic dance necessarily moves to. Personally, I need the kind of music that lifts me from the kitchen floor I’m swabbing clean with ragged towels some rainy Sunday in April, a jazz riff, a folk ballad, or a rock jam that beckons me into the middle room for a full-bodied groove across the bare wooden floor.

Poetry and dance are like Vermont apples and Florida oranges that, thanks to the miracle of refrigeration sciences, end up in the same row of crates at the market every single day of the year, no matter how far out of season either one is, no matter that the poetic apples ripen and fall in the autumn and that the balletic oranges drop to the sandy loam down south when snow has already filled the orchards and ice has glazed the limbs up north.

If poetry, as Thoreau said, is kind of like a marriage of music and philosophy, then dance is probably like a marriage of the movements made during manual labor (or maternal labor, if you prefer) and those made during the dreams of disturbed or enchanted sleepwalkers.

When I pay my way to see the big names in dance companies who come to Boston—Mark Morris, Bill T. Jones, Paul Taylor, Twyla Tharp, and others—and when I see the lesser-known performances at the Green Street studios in Cambridge—the same holds true: I like best the dances that make me want to get up and dance. Whether it’s the Alvin Ailey troupe dancing to Otis Redding songs or Mark Morris’ dancing to Handel, I don’t care. I’m infected by the exhilaration of the dancers exulting to the music, serving the moods and stories suggested by the music with moves that the shocked audience to a person recognizes with applause at the end. And I like that too: the chance to let go and stand up with everyone else and shout out my approval!

I see Sarah Tyler working herself up into that moment all by herself, making personal poems that are connected to the public experience like stems to the orange caps of toadstools that green toads crouch under for shelter.

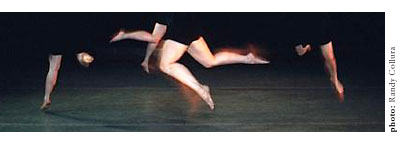

And several days later I still see Kelley Donovan, in bold and joyful crimson and purple, working to create that liminal atmosphere in Killian Hall to a recording of postmodern rainforest music by composer Michael Oster. From the speakers comes the misty music of pipes, tom-tom, triangle, and vibes evoking the Edenic but dangerous texture of a jungle in the Congo or the Amazon where so many toads find shelter under toadstools. Energized by the music, Donovan no longer calls to mind the lusty milkmaid or gopi in this, the most interesting and captivating dance piece on the program because it’s the one most integrated with its motivating source. For this dance she has had to learn what it feels like to live in other bodies; has had to get inside the body of the rainforest creature and see how her senses react to all those species around her, many of which are crying out in the darkness at once. Her dance shows how enchanting it is to be a creature of that forest, and how scary.

I still see Donovan feeding off the musical representation of the mysterious and wild places that are home to most of the earth’s species of plants and animals, and feeding off it with more apparent vitality and authentic feeling than she could to the poetry. I see the music turning her into a tropical animist creature of that woodland (albeit with a friendly North American smile seemingly adaptable to a variety of ecosystems), crouching and wheeling, spirited by the sound. I find myself wishing that Donovan had done more than one dance to music during this performance, and that I will get to see her do an entire performance to music sometime soon in the Artists Behind the Desk Series she must be proud to organize.