There is the right way and the wrong way for budding artists to present their work to dealers or curators for possible inclusion in exhibitions. As the Assistant Director and Curator of a reputable midtown Manhattan gallery of 29 years standing, who in the course of any given week receives between 10 and 25 inept inquiries by artists seeking representation, I feel it my duty to divulge a few straightforward facts for those who take their work seriously. Artists of all disciplines generally start out with romantic intentions. The reality is that working artists are in a business not unlike any other, and must learn to play the game. Fortunately, artists need not separate themselves from their own philosophy and aesthetic pursuit in order to succeed. What requires separation is fact from fiction, art from politics, and a broken heart from a beating one.

Searching for a representative is not the same thing as searching for an apartment, though judging by some artists’ actions, one would think the opposite. An anecdote: A young, handsome man walks into the gallery one afternoon carrying a large portfolio case. Without introducing himself, he opens it and pulls out a technically excellent realist painting on paper in acrylic, a la the photographer Bedrich Grunzweig. Like a door-to-door salesman, he has in one fell swoop made two critical errors. First, he is in a gallery that represents only abstract expressionists, and secondly, he does not have an appointment. Then, to my embarrassed astonishment, he literally falls to his knees and hollers, “What do you have to do to get in a gallery these days!?”

Research, for starters. It amazes me how little is done. Attending the opening receptions around town and asking questions is a good way to learn, as well as a way to establish a face with a name. Invariably, though, what you discover is what Vladimir Nabokov referred to as “Poshlost Exhibitionism”, or men and women going to the bathroom in pairs (connotations aplenty)—a great deal of posing and very little art appreciation.

The most common mistake artists make when introducing themselves, other than the aforementioned lack of research and appointment setting, is addressing a poorly written letter to “Dear Director” or, worse still, flooding galleries with general interest e-mails with their work attached. True, the technological revolution is wonderful, what with the advent of important international artist registries, research and provenance possibilities, and communication advances. Digital imagery, however, is an inexact science and gallery directors do not take it seriously when an artist types “Please visit my website” and pastes a link. That is not unlike soliciting, or getting a Christmas card from a creditor.

A portfolio is the best way to present one’s work. It should contain an introductory letter that is to the point (addressed to the proper individual and his or her title, of course); a curriculum vitae (biography, exhibition experience, awards, bibliography, public collections); a selection of at least six slides (labeled!); an artist statement and any relevant reviews. Gallery directors are not in the business of taking risks with unknown artists, so suggesting clientele to the gallery bodes well. If you want the portfolio returned, include a self-addressed stamped envelope. Surprisingly, this is not common knowledge whatsoever. There are stacks of portfolios doubling as foot rests under the desks of every gallery director in the nation.

Where the socializing aspect is concerned, a long sexist history in America’s art world has been duly recorded. As recently as the late 1970s, the artist Judy Chicago was labeled a feminist by the anxiety ridden, male dominated world of dealers, which created more panic and fear than intellectual discussion. Last year, New York artist Dafna Mordecai contacted a very well-known art critic and editor for possible inclusion in an article on emerging talent. The editor’s assistant took her to a restaurant for an interview and afterward told her in no uncertain terms that their interest in her was not for her abilities as an artist. She rightfully refused his lame advances and was subsequently taken out of the article. “You have to ask yourself what is truly on a dealer’s or an editor’s mind,” Dafna said. “Are they interested in you as an artist or is there something else? It’s important to get involved with others in similar positions and to introduce yourself, but you have to be careful. You can’t throw yourself at them.”

Furthermore, unless artists are willing and able to foot at least part of the tab for an exhibition, they need not even try. Some galleries in New York charge an artist $20,000 before they even let a painting in the door! What’s that song from “Cabaret”? Money Makes The World Go Round? Ridiculous, but true.

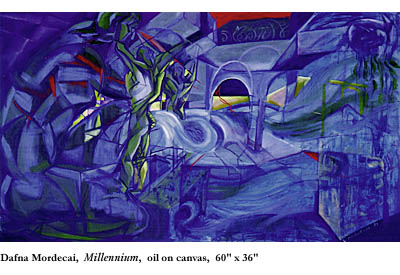

Ours is a period in history in which art screams for attention, from the Chapman brothers’ insipid portrayals of men and women as brutal and blunt phallic ornaments, to the concept laden lunacy of ’90s Whitney showcases. Fortunately for us, Ms. Mordecai reminds us of a time and a place where the confluence of cultural experience and mythological spirituality remain meaningful. They are ideals exceptionally embedded within her creations. She also understands that if getting from point A to point B in the political atmosphere of the art world (“boy’s club” as she calls it) means having an exhibition at a not-for-profit basement showroom, where the pipes fight for prominence with the paintings—if this is what it takes to succeed, and is what being an emerging artist is all about, then so be it. She is showing her work and she believes in it because it comes from inside. Sacrificing your pride to improve yourself increases the limit of possibilities, for they are not as unlimited as we have been led to believe.

Dafna Mordecai blends a classical perspective with the passionate mind’s surreal landscape. War and peace, love and longing, celebration and the spirit of life live in abundance throughout her body of work. Here, human figures strut and fret amid an explosion of energy and color while somewhere far away is the elusive dream of an ideal harmony, hovering within our human reach. That her formal training under David Passalaqua at Parsons School of Design gave her discipline and knowledge in the ways of the old Masters is noteworthy, though it is her inner passion that sets her paintings apart, a soul-driven longing apparent in the joie de vivre of her palette.

For budding artists, things may sometimes seem hopeless. Yet when faced with the improbable, it is the determination to make it seem otherwise that separates the false romance from true accomplishment. Effort, when applied intelligently, forces life to yield, and allows an artist to sleep at night.