Hearing about the event, I wondered how selections by Weber, Ravel, and Dvorak would compare in the same musical venture. Compositionally and stylistically, the composers have nothing in common, as each flourished in a different place and time. However, aesthetically, the three draw heavily upon imagery. What image or impression could be traced in an evening’s performance?

I went with this question in mind to the Boston Chamber Music Society’s performance at the Longy School of Music in Cambridge this summer. The results proved impressive and imaginative.

The BCMS prides itself on choosing composers that do not necessarily fall into the same historical period or musical movement. One previous performance found Haydn, Shostakovich, and Schumann on the same program—three giants generously separated by time and style.

Pickman Hall at Longy School is a room with many nice features. A wide floor and a high ceiling grace the interior, which conjoin at the stage in front. The fine wood paneling on the walls creates warm acoustics complementary to trio chamber music.

Cellist Bion Tsang and pianist Mihae Lee took the stage and would anchor the three selections throughout the performance. Tsang, a world-premier cellist, plays equally well in the orchestral world, including stints with the New York, Moscow, and Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestras. Lee, a regular member of the BCMS, masters a career as a world-renowned soloist and chamber player, with highlight performances at the Lincoln Center and Kennedy Center.

New York Philharmonic flutist Renée Siebert first joined the two for Weber’s Trio in G minor, a four movement delight. The opening allegro surged with beautiful, fluttering piano and flute lines with a playful cello underneath. The technique of each player soared with mastery, while the tone of each instrument, fleshed out by the room, resounded with power.

By the second movement, I was beginning to understand why this piece, in particular, may lead us to Ravel and Dvorak. Though strongly rooted in an expressive, Romantic quality, it foreshadows the Impressionist movement that Ravel was certainly a part of and for which Dvorak helped pave the way.

The third movement, andante espressivo, captivated the listener with imagery and mood. I imagined the calm before a storm with leaves rustling, gates closing, dogs barking and ominous clouds overhead. The final allegro movement fulfilled my expectation of a storm. Tsang’s cello had burst with furious lines, with Lee’s thundering piano and Siebert’s lightning flute flowing from above. The finish was remarkable and impeccable.

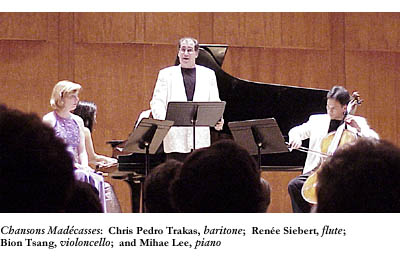

If this first piece pleased the ear, heart, and imagination, the next piece would challenge them. An atonal and unsettling Ravel vocal composition based on Eraviste de Parnay’s poem Chasons Madécasses. Based on songs from Madagascar, the poem celebrates the exotic and primitive beauty of coastal Africa, while railing against madness of colonial invasion.

Baritone Chris Pedro Trakas, a singer with remarkable performing and recording credits, commanded the piece with great vocal depth and precision. Dynamics were the key here as Trakas gently sighed over the subtle Nahandove amidst Lee’s atonal, wandering backdrop. The flute and cello lines were scattered and abrupt, breaking off and rejoining at uneven points. The performers were drawing a line of outright contrast between this and the Weber piece. Yet, though completely different in musical form and style, the mood felt similar to the first piece—a calm before a storm.

Not a soul in the audience rested easily as the bellowing, rupturing voice of Trakas belted an “Aoua, Aoua!” (Beware, beware!) to begin the second movement. It was a paroxysm so vital and real—if this man started to thrash violently about the room, the audience had fair warning. By the third movement, the storm had subsided into a steady rain. Siebert’s flute and Tsang’s cello drew the vocals inward. The music retreated into a more pensive, romantic yearning.

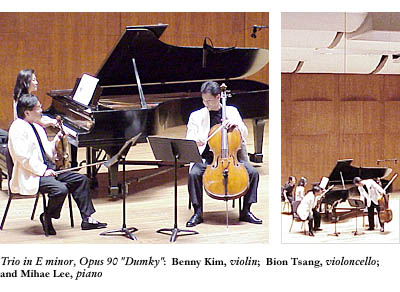

Previous to intermission, Trakas and Siebert left the stage to make way for the final trio performance. Benny Kim joined Lee and Tsang for Dvorak’s Trio in E minor, Opus 90 “Dumky”. Mr. Kim is one of the top violinists in the world, having performed with almost every major symphony in this country, and throughout Asia and Europe.

The program notes point out that Dumka (plural Dumky) is a kind of Ukrainian folk song. Dvorak’s unique style relied heavily on his adoration of folk-dance music of Eastern Europe. There are six movements to this piece. Though shorter in length than the normal movement, it can be awkward to hear the third or fourth movement end abruptly without wanting to applaud. (This actually was the case as an embarrassed audience member prematurely clapped after the fourth.)

The music is utter delight as we are back to rich and harmonious tonality reminiscent of the Weber piece. Sweeping, flowing violin and cello lines dance and make merry with a busy piano underneath for the first movement. The slow second, third, and fourth movements drip with emotional beauty, a melody-lover’s dream. These movements were the most engaging emotionally. The imagery is of a pelting drizzle against a window pane. The drops forming just slide down one after another.

By the fifth and sixth, Tsang, Kim, and Lee have whipped up their lines into astounding feats of technical wizardry. The stunning and vivacious chemistry of the trio pushes forward, not into the frenetic whirlwind of the storm, but into a joyful promised land. The piece ends and the tension eases into a peace and a renewal. We have come full circle in the impression of a storm.