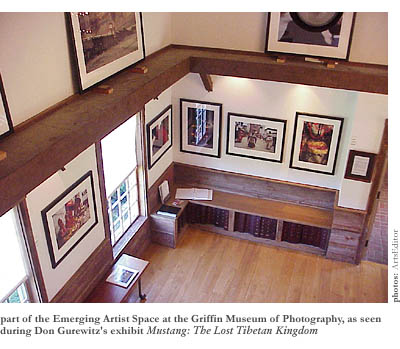

The unique opportunity to glimpse a semi-secret Tibetan kingdom currently exists in Winchester, Massachusetts, home of the Griffin Museum of Photography—another treasured kingdom of sorts. Founded in 1992 by Arthur Griffin, the museum houses three galleries devoted to rotating exhibitions of photography. In one of them, award-winning photographer Don Gurewitz graces us with images unimaginable to Western eyes, captured in their final form as vibrant Iris prints on watercolor paper. Gurewitz’s attendance at the Tiji festival in Nepal’s Kingdom of Mustang required special permission and an arduous five-day trek through the Himalayas. Those interested in all things Tibetan can skip the treacherous hike and simply walk three minutes from the train. The Griffin’s Emerging Artist Space—still emerging itself—is where Gurewitz’s images of the world’s last forbidden kingdom find a temporary home in the exhibit Mustang: The Lost Tibetan Kingdom, on view through October 31st.

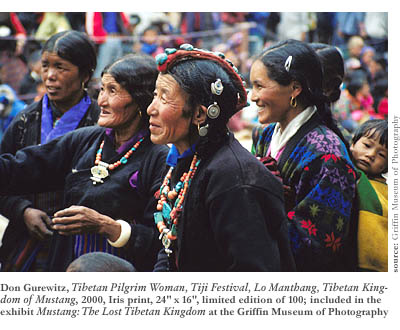

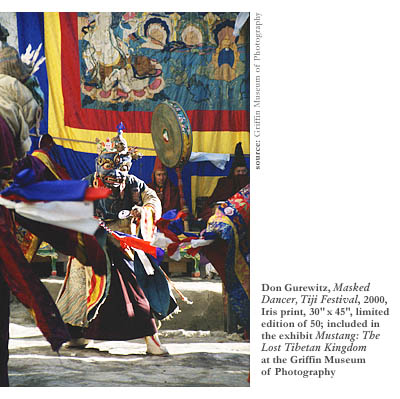

Gurewitz, a Cambridge-based documentary photographer, joined forces with ten inveterate travelers, receiving permission to enter Mustang in 2000. Nestled in the Himalayas at 13,000 feet, Mustang is a Tibetan kingdom that falls within the boundaries of Nepal. Its capital, Lo Manthang, is a medieval walled city, within which the Tiji festival—a purification ritual—takes place at the beginning of every harvest season. The origins of the festival predate Buddhism, born out of an animistic and shamanistic tradition. Gurewitz and the travelers he accompanied became the voyeurs of a living history; the costumes and dance steps of the Tiji festival have remained the same for over 600 years.

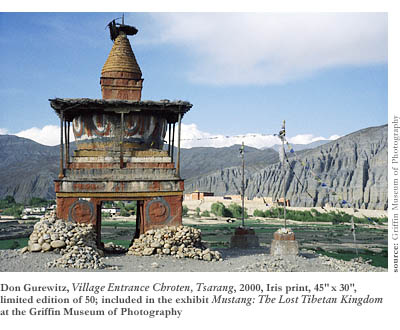

Because of its isolation and unique alliances with the leaders of Nepal, the semi-feudal kingdom represents perhaps the purest existent Tibetan culture in the world. The history of Tibet itself is an imbroglio of warring sects, involving the sublimation and destruction of kingdoms, all incited by the significant doctrinal differences between them. The Kingdom of Mustang remains a thriving testament to the Red Hat sect of Tibetan Buddhism (unlike the Yellow Hat sect to which the Dalai Lama belongs) and is the only surviving continuous Tibetan monarchy, currently ruled by a direct descendent of the very first king.

The twenty-four prints chosen for the exhibit bring to life the three days of the Tiji festival, capturing an array of colors so bright they’re almost dubious. Even more fascinating than Gurewitz’s ability to capture and reproduce color is the knowledge that the townspeople procure every color manifest (as well as any form of sustenance) from the arid vastness of this never-never land. The exhibit lends a sense that the Kingdom of Mustang is the farthest place from anywhere—only Mars seems more remote. And, these days, one can at least see Mars from here.

Gurewitz also documented his approach to the tucked-away city of Lo Manthang, to which there exist no immediate roads or airports. Captured on film are landscapes most Westerners will never encounter, detailing juxtapositions of desert and ice-capped mountains and implying a vastness that extends infinitely far beyond the human capacity to see. If a five-day hike at upwards of 13,000 feet wasn’t enough to knock the wind out of our fearless travelers, the penetrating winds may have occasionally done it. The approach to Mustang requires travelling through the world’s deepest canyon, which is one of the windiest as well. Gurewitz took his 100 rolls of film on three different professional rubber-sealed cameras, each falling victim one by one to the infiltrating, pelting sand. The air racing from the ocean and across the plateaus into the mountains finds great opportunities in the paths cut by rivers, funneling rapaciously down the natural alleyways.

The faces Gurewitz has captured are remarkable. These are bodies that have weathered all elements and thrived in spite of them, and yet there is a sensitivity captured in the photos of the nomads, townspeople, and monks that so effortlessly epitomizes what it means to be human. Eyes light up at the sights and sounds of the ceremonies. Women are drenched in turquoise and silver. Informal performances after nightfall expose the awkward shyness of those preparing to sing. Showcasing personal repertoires of song and dance has become part in parcel to the celebration. The ways in which people persevere in the face of the elements and express themselves creatively and aesthetically in their pursuit of survival is a dichotomy that fascinates Gurewitz and inspires much of his work.

The tips of the red hats worn by the Lamas comprise one photograph, Lama’s Hats, Tiji Festival, which from a distance looks to be an intimate portrait of a rose or bright red tulip. Upon closer examination, the fabric comes to life, and it is these details Gurewitz refuses to spare. Despite any debate about the authenticity of Iris prints, the highly refined equipment, in the right hands, can chemically compose magnificent, oversized, vibrant images.

Perhaps no one respects people’s ability to persevere more than Don Gurewitz, who has traveled to over fifty countries spanning five continents, capturing dignity, grace, and creativity in those inhabiting earth’s nooks and crannies. Making his living as a machinist for General Electric Co. in Lynn, Massachusetts, Gurewitz experienced frequent layoffs and yet has always taken full advantage of what he considers the mixed blessings of downsizing. He has spent any and all free moments traveling the world, finally taking advantage of a sizable number of frequent-flier miles accumulated while investigating labor issues abroad.

Gurewitz’s photography resonates with a social sensitivity bred from a lifetime of political activism. An entirely self-taught photographer, Gurewitz used the camera as a journalistic tool during the Civil Rights movement, anti-war demonstrations, and while dodging bullets during the civil wars in Nicaragua and El Salvador. As has been the case with most of his travels, Gurewitz’s trip to the Kingdom of Mustang has engendered numerous lectures, all accompanied by an array of colorful and provoking slides. At the Griffin, an artist gallery talk and slide presentation is planned for Thursday, October 16th at 7 pm.

In stark contrast to Gurewitz’s work are the exhibits that are coming and going in the Griffin’s main gallery. The remains of Photobooth lay scattered about—an exhibit that drew quite a bit of attention. And in its place is Jan Staller: A Retrospective, up September 25th through November 28th. Those unfamiliar with the New York-based artist’s large-scale color photographs will likely be infatuated at first sight with how his somewhat mundane subject matter (spools of thread, industrial ruins) appear imbued with an ethereal and alien energy. Meticulous framing of the objects and the mix of natural and artificial lighting run in complete contrast to the photo-journalistic style of Gurewitz, who doesn’t even so much as crop his images. Capturing an extraordinary people and a unique experience, Gurewitz aims to make photographs that are approachable and accessible in terms of cost, education, and reception. While he captures the experiences of ordinary people in far-off places, Staller’s work obsesses over the ordinary, making it into something otherworldly, offering a sense of transport in a much more figurative sense.

Executive Director Blake Fitch clearly has no fear of straddling the two artists. Since Fitch’s appointment in February of 2001, the museum has become a rather hip and cool place, adding to the Griffin’s repertoire significant exhibitions with broad appeal. Aside from its commitment to present contemporary and historic works as well as emerging artists, the Griffin Museum of Photography exists as a tribute to New England’s “Photographer Laureate,” Arthur Griffin, who spent more than sixty years as a photographic journalist. The Griffin Collection includes more than 75,000 negatives, transparencies, rotogravures, and vintage prints. It is home to color and black and white photographs of Ted Williams’ first year with the Red Sox—the only display of such in the world.

Exhibits that extend in all directions within the medium are what make the Griffin a museum, after all. And a museum worth frequenting.