December 1st saw the commemoration of the last World AIDS Day of the century. It was, indeed, a worldwide event. Focusing on the devastating effects the disease has wreaked upon nations, specifically in the third world, activists chose to turn the focus of this year’s events onto the children orphaned by the virus. Though the AIDS epidemic seems to have virtually plateaued here in America, we have seen more people die from the disease in 1999 than in any year since the disease was first recorded. Despite this, there are many faces of AIDS, specifically those in Africa and Asia that are not as familiar to us. Some 4 million people fell prey to AIDS in Africa alone in 1999.

This seemingly impossible task of bringing the AIDS epidemic to a halt garnered much attention from the United Nations, who released a report on December 1st, stating that 11 million children have been orphaned by AIDS-infected parents. In two years’ time, the number is expected to reach 13 million. Many of these deaths are taking place in South Africa and Nigeria, where HIV infects a new person every minute. Here, in North America, the numbers, while not as high, are equally as frightening. Over 70,000 children have seen one or both of their parents succumb to the worst disease of our time.

A recent article in the Boston Globe cited AIDS as a political issue, one that is inciting the anger from activists worldwide. A criticism of South Africa’s policy concerns President Thabo Mbecki’s decision to bring a halt to the administration of AZT to pregnant women, citing the toxicity of the drug as a reason. Glaxo-Wellcome, the manufactures of AZT, the most popular drug used to combat the effects of AIDS, has agreed to lower the price of the drug by 75 percent in order to successfully distribute the drug to countries such as South Africa. This attempt at wider and more affordable distribution will, of course, not solve the AIDS crisis, but will attempt to make it less of a reality for many children and adults.

In response to these towering numbers, politicians and activists strove to make an impact during World AIDS Day. Health and Human Services Secretary Donna Shalala released a statement urging people that “now is not the time to become complacent. We must continue to strengthen and expand prevention programs.” Secretary Shalala also emphasized the importance of expanding treatments for HIV/AIDS in minority communities. She finished her statement with an emphasis on the children orphaned by the virus, saying, “our greatest treasures and our greatest hope for the future are our children. It is for them that we must never give up the fight to end this terrible disease.”

Though much of her statement might be read as a series of political soundbytes, activists helped to emphasize Secretary Shalala’s points. AIDS activists handed out condoms on buses in Bangkok and once again spread the AIDS quilt over the mall in Washington, D.C.

![]()

Not only have there been (and continue to be) overt political demonstrations regarding the continuing spread of the disease, but visual artists have also found ways to convey unconstrained political messages. Perhaps a more popular and visible artistic subject at the onset of the disease, the AIDS virus has wreaked havoc among the nationwide and worldwide communities of artists. This fact, however, is not new information. Those who are fairly well informed know that AIDS has wreaked havoc in nearly every community, artistic or not. But, many painters, sculptors, and dancers once brought the disease to the forefront of art, thereby managing to wrestle much of the power away from AIDS. By creating art about a deadly disease, indeed about one’s mortality, there is much opportunity to reach a wide audience, to open the hearts and minds of those who would otherwise be ignorant of the devastating effects of the disease. It can be said that some of the AIDS-related art that reaches wide audiences is presented with a tone of hopefulness. But the question plaguing the panel of artists, writers, and critics (as sponsored by The Harvard University Arts Committee of AIDS) on the evening of World AIDS Day was: Is the disease still a valid metaphor? What more can be said about AIDS in American art?

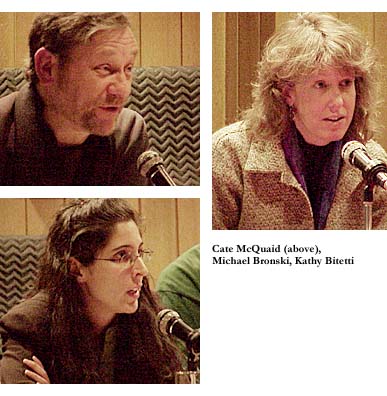

Those debating this issue and other related topics included artist/curator Kathy Bitetti, artist/activist Jay Critchley, choreographer/dancer Tommy Neblett, and writers Michael Bronski and Cate McQuaid. Critchley began the evening with a slide presentation of selections of his work. Much of Critchley’s early work centered on various ensembles of sexual images, specifically of condoms. In the early days of AIDS, the relationship between condoms and AIDS was obviously a strong one. In more recent years, however, Critchley has shown the correlations between AIDS and environmental destruction, racism, and sexism. The encompassing of physical and mental destruction in his art serves as Critchley’s point that HIV/AIDS-related art has moved beyond the realm of overtly sexual images. Despite his argument, many of Critchley’s slides concerned themselves with these clear sexual images, such as his “Lympdick Project: It’s Hard To be a Man.” The aforementioned work is an attempt to debunk the myths of the phallic metaphor of masculinity in the age of AIDS.

Choreographer and dancer Tommy Neblett next took the stage, speaking specifically about his evening-length dance piece, “Ecstasies and Devotions.” Broken into five sections, “Ecstasies and Devotions” is about a relationship in the age of AIDS. The first section deals with coming out, the second with bar life, the third was inspired by Neblett’s first lover who died, the fourth is a duet of support and tenderness, and the fifth, entitled, “Requiem,” deals with grief. For Neblett, he did not initially envision his piece to be about AIDS. That is, he did not begin writing and choreographing the piece with HIV/AIDS in mind. Despite the subject of “Ecstasies and Devotions,” Neblett does not see his piece as wholly pessimistic; rather, his piece, from the viewpoint of a survivor, has much to do with hope.

Following Neblett, activist and artist Kathy Bitetti spoke briefly about her involvement with such AIDS activist groups as ACT UP and Visual AIDS Boston. Despite Bitetti’s obvious involvement in such activist groups, she bemoaned the loss of activities with each World AIDS Day. Perhaps this lessening of activities on each year’s December 1st has much to do with her perception of how the outside world continues to see the virus. On this topic, she said, “As far as I’m concerned the ‘straight world,’ as I like to call it, doesn’t even think it [the AIDS epidemic] happened to begin with. There are a lot of people who don’t even know it exists.”

Following Bitetti’s strong convictions, writer and critic Cate McQuaid stated that there are fewer articles written and published in recent days about AIDS than when she first began as an art critic in Boston. From McQuaid’s early days as critic, she remembers “… how many stories were written in the South End News in the Arts section about art and artists who were dealing with AIDS and we were just covering the neighborhood of the South End … it’s really interesting to see how much that has decreased.” For McQuaid, art that deals with HIV/AIDS simply isn’t popular anymore. In her own words, “AIDS doesn’t sell.” There are, of course, many ways to change this, to make AIDS-related art a commercially viable venture for collectors and curators. McQuaid’s solution is for AIDS-related art themes to be conveyed in new and different ways. Though no specific examples were cited, this would, for McQuaid, solve the problem of AIDS-related art not being commercially viable.

Writer and moderator Michael Bronski then posed the questions, “Can art save people from AIDS?” and “Is AIDS art ‘victim art’?” In response, Neblett said, “Yes. I believe art can save someone from AIDS.” In Neblett’s view, that is one of the purposes of art. There is, however, also a larger purpose – AIDS-related art has a responsibility to heal. Neblett believes that “Ecstasies and Devotions” will help to heal, rather than to save.

![]()

On this point, Bitetti stressed the importance of courage and hope in art. For her, the idea of AIDS art as ‘victim art’ is “infuriating.” She continued with her point about varying perceptions of AIDS in America, saying that many people may have “problems” with sexually charged art. Perhaps America’s supposed reluctance to embrace AIDS-related art is surrounded by a strong fear of sexually provocative images. How, then, does one communicate information about a sexually transmitted disease to those unwilling to listen? One solution to this lies in films like Philadelphia – such mass media creations that are at once unrealistic and stereotypical, but also convey the story of an AIDS-infected man. On this point, Bronski asked if the commodification of AIDS makes any work about the disease less potent. For Neblett, he is grateful for any media attention paid to HIV/AIDS. In a way, making AIDS a commodity makes the disease more powerful; it makes the images seen very potent, because they reach wide audiences. Of course, Neblett contends, the commodification of the disease waters down the images of AIDS.

There are, to be sure, many facets to the AIDS crisis. It is clear from the panelists that AIDS is still relevant within art, even with the challenges it faces today. It is also clear, however, that nostalgia has a grip on many feelings about AIDS art. Nostalgia alone isn’t going to make AIDS art more relevant to a contemporary society. In the minds of most people, a resurgence of AIDS art will require more than mere sentiment and longing for the heyday that was the 1980s.

Yes, AIDS can “sell” once again.