“We’re not afraid of the real world down here,” says Bernie Toale, sole proprietor of the Bernard Toale Gallery, located in a renovated building on Harrison Avenue in the South End that includes a number of other galleries and studio spaces. He’s answering a wise remark about the proximity (right next door) of the Pine Street Inn, Boston’s largest and best-known homeless shelter for men. A large print of gulls, silhouetted black against an expansive green background, blocks most of the view from the gallery’s rear window, but around the edges of its frame that real world can still be seen. Some bruised soul with a scabbed brow and no change of underwear is probably dragging his ass gradually down the street toward Saturday supper, having spent most of the day snoozing at a table in the Copley Square library. And some other utterly artless man is maybe making his way here from a hot-air vent in the sidewalk outside of City Hospital, a few blocks away.

Toale’s relaxed response, with its implicit sympathy for the homeless victims of mental illness and real estate speculation, has an especially clear ring to it now, because the photographic works on view in his small gallery—the “grids” of San Francisco artist Chris Komater—are, like the Pine Street Inn, both of the “real world” and all about men. They aren’t photojournalistic shots of homeless men, however, but modestly erotic studies of the graying, unglamorous, and somewhat paunchy school of middle-aged gay men known, in gay-and-lez households across the land, as “bears.” Bears made all the more cuddly, it would seem, for the unflinching, magnifying scrutiny that their anatomies are subjected to by Komater’s cool yet compassionate camera.

Of the eight photographic “grids” on display in the show—grids in this case being symmetrical arrangements of individual, framed photos spaced an inch apart to form a single pattern, like mosaic squares that form the image of a flower or a goddess—only two do not concern middle-aged males. Those two, titled Betty Grable and Turner (as in Lana), are studies of the seemingly indestructible curls in platinum blonde hair-dos. For all their sincere curiosity in the inner workings of the curl, nevertheless an unfortunate cliché dominates these two pieces—gay men must simply adore the Hollywood glamour gals of yore, because it says so in fashion magazines. Yet the cutesy campiness of these prints serves to highlight by contrast the real sense of discovery in the six studies of bears.

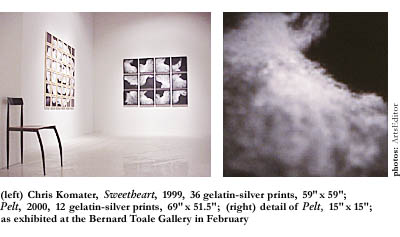

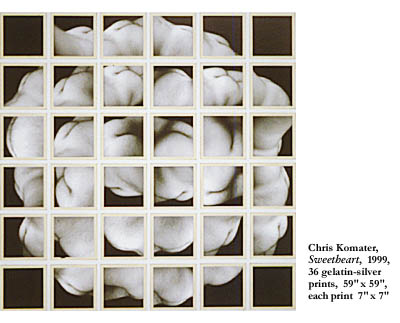

Sweetheart, the first piece seen upon entering the gallery and the last one lingered over upon leaving it, with time becomes the most treasured discovery. A grid of 36 black-and-white prints (six of them in each of the six even rows, each print measuring seven inches square), this large piece pays an unembarrassed, if slightly embarrassing, compliment to the model’s pale-plum posterior. Erotic in the old sense of the word—sexually loving more than sexually lustful—it offers multiple views of the ripe, tan-lined fanny. Each print takes a long, close look at the curvaceous biscuit from a somewhat different angle—sometimes from this side, sometimes from that; afloat here, astride there—so that the defining elements of the image (i.e., the cleft between the buns, the dimple of the hip, and the tan line itself) become more and more familiar, more and more revealing, as if the character of the model, whom we know only from this rear view, was being suggested by the “minute particular” image. A part, it seems, is standing tellingly for the whole. (Synecdoche, they call that.)

The individual frames of Sweetheart please plenty, more and more with repeated visits, loaning the viewer the kind of musty eyes Walt Whitman wore when he noticed “the strong sweet quality” that “strikes through the cotton and broadcloth” of the shirted backs of workingmen passing in the street. But the kaleidoscopic round pattern that the singular images form when seen from afar, with only the four corner frames left black and the adjacent frames filled with flesh to graduating degrees, doubles the pleasure. The lightly fibered and quietly freckled skin, providing tonal variety from the whiter buns, tanned waist, and much darker cleft, cannot be seen from a distance; but what can be seen is the roundness of the whole, the almost rose-like shape on the gallery wall: a complex chiaroscuro of petals. The planes of the contoured figures toward the edges of the pattern nearly meet, so that the waist of one print connects very nearly to the jutting hip of another print. The arrangement produces a curious kind of optical illusion. It’s not only a rose now but also a picture of one rather fleshy, anonymous object cut into a lot of perfect squares that have been segregated just slightly; and now it looks as though the vulnerable, venerable rear ends were all in orbit, the one butt turning and turning in the widening gyre, helplessly babylike at the loss of gravity, round and pattable, in need of the individual attention of the intimate viewer who has stepped away from the pictures. This is where the comedy becomes divine.

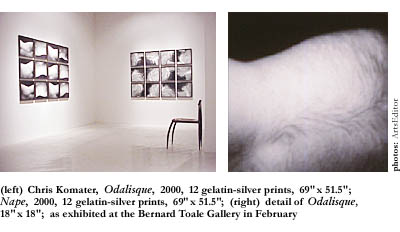

Sweetheart‘s interesting contrast—or maybe contest—between meaty content and abstract design is evident in the other variations on the grid theme. Odalisque, for example, shows at once the excruciatingly specific images of the bare back of a man reclining on his side and the general pattern of waves they form in sequence. Arranged in three rows, with four black-and-white prints in each row, the individual images—unadorned, objective, matter-of-fact views of the man’s hirsute back—would repel the heat-seeking eyes if it weren’t for the pattern, which at once softens and abstracts them. Each long hair on the back can be seen and measured, almost pulled from its lock it would seem; every little occasional freckle shows under the waves and tufts of hair; the trench of the spine is there—at least that’s what that must be, right?; and a waistline and hip might be suggested, too. (The man is so close you could practically smell and touch him.) But seen in retreat from the wall, each row of four prints goes left-to-right in a kind of wave, the first and third and the second and fourth prints in each sequence being roughly even with one another—hence a symmetrical alternation in the pattern of each rippling row.

The title Odalisque, not referring literally to a Turkish concubine but connotatively to the rear-view studies of the models who posed as Turkish concubines for Ingres and other French painters of Oriental exotica, suggests ironically an ordinary gay man’s countercultural statement against received standards of beauty. “Here is the back of an actual human being,” Komater seems to be saying, “made more vulnerable and pitiable somehow for the absence of other detail. No classically beautiful face, velour divan, or Grecian urn is needed now. And most of all, no objectification of idealized women.” Man is but a “poor bare forked animal,” says Shakespeare’s shivering Poor Tom to Shakespeare’s bedraggled King Lear out on the heath. These pieces support that statement courageously.

Nape, a close-up study of wiry gray neck hair that swirls and loops in silver curls through the black space around the multiple arrangement of prints, works along the same principles as Sweetheart and Odalisque, drawing the viewer forward for a closer look at the individual prints and pushing the viewer away for a scan of the coherent, abstract pattern. So does Pelt, an intimate look at the upper back, the back of the head, the neck, and the ears of a graying, ungrowling bear, providing an irresistible illusion of invaded personal space. These two kaleidoscopic grids aren’t as charmed or disturbing as Sweetheart or Odalisque, but they do go some ways toward completing a comprehensive view of the bear bare body. It would be nice to see them in a larger exhibit that included Komater’s studies of other anatomical parts.

Nape, a close-up study of wiry gray neck hair that swirls and loops in silver curls through the black space around the multiple arrangement of prints, works along the same principles as Sweetheart and Odalisque, drawing the viewer forward for a closer look at the individual prints and pushing the viewer away for a scan of the coherent, abstract pattern. So does Pelt, an intimate look at the upper back, the back of the head, the neck, and the ears of a graying, ungrowling bear, providing an irresistible illusion of invaded personal space. These two kaleidoscopic grids aren’t as charmed or disturbing as Sweetheart or Odalisque, but they do go some ways toward completing a comprehensive view of the bear bare body. It would be nice to see them in a larger exhibit that included Komater’s studies of other anatomical parts.

It would also be nice if Beanstalk, a vertical alignment of eight studies of one man’s torso, were included in such a show. This piece gives us a significantly more complete view of the model’s body, some of the prints providing views of the entire nude trunk. But not the whole body is here, for the head and shoulders of the man are cleverly cropped, so that character again must be inferred from elsewhere but the face, the easiest place to read on the body. The viewer—the benevolent voyeur—can look up and down the towering column of photographic images at the torso twisting three-quarters this way and two-thirds that way, toward the camera and away from it, corkscrewing up and down the wall; can take all afternoon leaning against the opposite wall to study the wrinkles of the experienced knee, the musculature of the well-seasoned thigh, the tip of the ruddy penis, the roll of the hairy belly; can get out a drawing pad and start a frank sketch of the nude right there; and, spared the disturbance of meeting the model eye-to-eye, can appreciate him for what he is. Not a studmuffin. Not a golden boy. Just an animal with a soul.