In preparation for a visit to Doug Bell’s show at HallSpace on Norfolk Avenue in Roxbury, it’s useful to stop at the nearby corner of Hampden and Melnea Cass Boulevard for a glance at the faded white lettering on the south-facing side of the two-story brick Bay State Auto Spring building. It is a business that has been there for years, surviving the neighborhood’s transitions over the past several decades, from bustling blue-collar blocks of light industry to fringe-of-the-slum wasteland to urban-revitalization zone. A glance at the words, and at the corresponding logo of a muscle-man uncoiling an industrial-strength spring over his head, will set the mood for the affectionately ironic assemblages of rusty hardware and beat-up basement-workshop furniture that comprise a good deal of Bell’s work. It won’t hurt to notice that the Bay State Auto Spring people, realizing the near illegibility of their old stencil, have slapped a metal sign, with the same block-lettered words and outrageously dated logo, on the east-facing front of the building, so that auto-parts retailers coming off the Southeast Expressway at Mass. Ave. in search of springs can easily spot their intended destination. If that doesn’t stimulate the historical curiosity, to imagine the grimy hey-day of the street, concurrently warming the imagination to the surreal nostalgia of Bell’s Beuysish collections of Americana, nothing will.

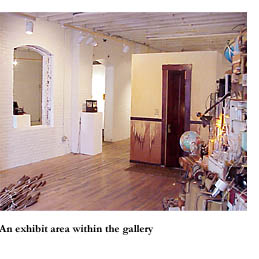

Nor would it hurt, climbing the stairs to unassuming proprietor John Colan’s second-floor gallery, to remember that the brick edifice it’s in once housed the wares of wholesale florists. Something, at least, will need to account for the sense (the scent?) of frivolity and gaiety that survives what, from factual description, would seem an insufferably somber show. Right there in the middle of the main room, for example, is the lovably dreary centerpiece, The Closet, consisting exactly of that: a wood-framed closet, about eight feet high and three feet wide, that the artist has constructed, according to Colan, independent of the larger wall he built on-site to install it in. The portable closet’s narrow, darkly stained door is ajar, its cold metal knob inviting the onlooker to take a peek inside at the strangely familiar, utterly ordinary objects. A hand-broom and a leather belt (of the artist’s own making) hang by hooks under the ceiling’s bare light bulb that shines just a bit too brightly for comfort. A long-handled broom leans in one corner of The Closet, and in the other corner lean a threatening pair of long sticks. The Closet is just barely big enough to stand in, until you’ve decided to be good, after the whipping. And it must be a basement closet, because the brown walls of its casing bear yellow stains—stains the artist has painted on, it’s important to remember, to resemble the kind that come from water-leaks during mournfully heavy rains.

To tell the truth, though, The Closet does not catch the eye immediately upon entrance into HallSpace, because the door of The Closet faces the opposite wall. The mesmerizing experience of beholding the The Closet in all its contented absurdity comes only after several other pieces have generated a mood of sullen amusement at the bleary Catholic blue-collar cold basement blues that so many Bostonians were once so used to—around 1958, say, when the guys who worked at Bay State Auto Spring were coiled tight like boxers.

Bell’s use of imagery is usually more frankly metaphorical than it is imitative, often generating energy from the ironic contrast of mechanical and religious images. There’s the simple symbolism of He Knows If You’ve Been Bad or Good, for example, an open suitcase full of crucifixes in unstopped beakers and lidless jars; dozens of crucifixes, that is, many of them as marvelous as exotic jewelry, arranged by size the way a Rocky Marciano-loving handyman in his workshop might have arranged bolts or nails in his basement workshop. (Small ones in front. Big ones in back.) There’s the spare symbolism of the Speedaway snow sled that’s being pulled on a rope (slightly upslope) by a plaster cast of the artist’s hand emerging from the back wall—an earthbound sled that in turn is dragging a dozen or more of those old-timey window weights that are now taking up space in the museum-like basements of hundreds of triple-deckers in Dorchester and Brighton. A haunting observation about childhood’s carefreedom being dragged down by homely, demoralizing forces. There’s the likewise tragicomic symbolism of Crosses and Dice, featuring a hardware scale with a semipreciously bejeweled pile of tiny and delicate crucifixes on one side and a variegated aggregation of big goofy dice on the other, neither one able to tip the scales its way—as if to say either (or both) that the working class gambler can keep his spiritual balance with Christ or that the impossible example set by the ascetic Jesus drives the working class Joe to gamble.

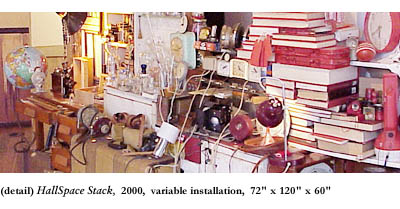

Yes, and there’s other stuff too. There’s Stack—a neatly compressed square-foot cube of materials (a stack of pictures; a transparent plastic window allowing a Joseph Cornellian view of a few obscure shaving-brushes or stamp heads in a row; and many antiquated paperboard hardware boxes in a variety of faded colors, for screw hooks, carpet tacks, nails, rubber bands, ink bottles, and the like). It fairly pulses with hidden power on its little wooden shelf on the wall. There’s the wood-framed glass box crammed full of empty, gleaming glass vessels, more oblique than Bell’s usual work. And there’s HallSpace Stack, an enormous collection of junk that Bell assembled on-site in the gallery, absorbing to inspect for its mere abundance of detail yet somewhat unyielding.

HallSpace Stack displays multiple examples of found objects under and on top of tables and desks and bookcases along one wall: discarded suitcases; crucifixes galore, in such superfluity that even Jesus’ agony begins to bore; broken scales (for bathroom weight-check and baby food balance alike); ominous, untitled, black volumes and equally untitled red plastic instruction-manual notebooks on shelves; alphabet blocks in a large upended jar—and alphabet blocks in an open suitcase underneath on the floor; empty beakers on one glass shelf above, jars full of steak bones on another; a dozen or more stopped clocks; and a globe, fitted onto a food grinder where its hopper used to be, that twirls at a dizzying speed when cranked (a counterpart to the three-wheeled canvas laundry hamper against a nearby wall, overflowing with globes) that bluntly contrasts the mundane and the celestial.

There’s all that—there’s even a playful collection of little boxes that are full of screws, vials, black masks, and stacks of black paper—and then there’s the title figure of Ballerina, the unfortunate martyr of the color-drained culture in question in this show. A chipped plaster figure with a pudgy grin, a conservative blonde hairdo like that worn in Soviet-era Poland, blue slippers and tu-tu, she whirls pathetically and continuously, at 33 1/3 rpm, on the turntable of a Masterworks hi-fi. The hi-fi’s encased in a transparent plastic box, it turns out, and she goes round and round in place on the turntable to the guttural groan of the hi-fi’s motor. The hi-fi she’s spinning on is, in turn, perched on top of a doorless metal cabinet. Inside the cabinet is a headless gray male suit-tailor’s dummy—the hollow man himself, representing, obviously again and again to the onlooker’s somber delight, sexless desolation—a reminder of what deadly horror awaits the ballerina should she stray from her socially prescribed path. Just as it is hard for a snow sled to gain momentum when dragged down by lead window weights, it must be excruciatingly difficult for a little ballerina in stereotypically feminine costume, spinning at a completely predictable speed for perpetuity, to find her own style of dance. She’s doomed, if not dizzy.

History for Bell seems to be a nightmare from which he is trying to awaken, as it was for the young literary artist Stephen Dedalus in James Joyce’s Ulysses, in a Dublin that sometimes sounds a lot like parts of Boston. Bell’s stacks and assemblages of salvaged materials, probably dragged from neighbors’ trash in the dark of night, are wakeful memorials to the exhausted people who wore the stuff out. They seem to commemorate the men of the house, mainly, who, looking into the smudged mirrors of cheap metal medicine cabinets like those flanking the Ballerina on the gallery wall, shrugged and kept on shaving, stropped razors flashing close to the throat in the unforgiving overhead light.