Two strangers are trapped in a tiny space. They move from mutual suspicion towards a tentative bond—before a final, explosive confrontation in which each reveals deep-rooted inhumanity. To writer William Orem, this is the essence of drama. “Claustrophobia and containment,” he explains, create a world “pared down to the dramatic essentials.” Orem’s play The Seabirds builds a formidable tale upon this structural purity. Argos Productions, the two-year old company that recently produced the play at the Boston Playwrights’ Theatre, likewise pursues an ambitious project grounded in the simplest of missions—to serve playwrights by involving them in every step of the production process. Orem and Argos, like any well-matched collaborators, thus share a desire to strip drama down to its bones. But this drive is contrasted with the sweep of their visions.

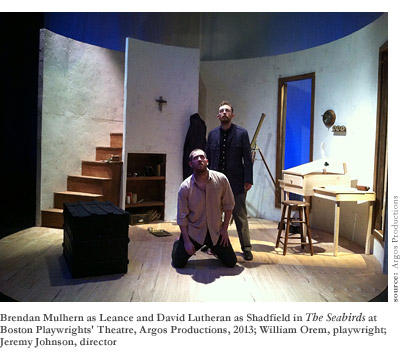

Forsaking the contemporary aesthetic of yuppie apartments and witty pop cynicism, The Seabirds takes place in a lighthouse on the Chesapeake Bay in 1863, the raging high tide of the Civil War. However intimate the canvas, the subject is undeniably epic. The story concerns Laban Shadfield, an obsessive, introverted Civil War lighthouse keeper played with unnerving deliberation by David Lutheran. One morning, he spots a man tossing in the surf, and hauls the half-drowned castaway up into his tower. The man turns out to be Mickey Leance, an Irish immigrant and Confederate deserter, depicted with explosive vitality by Brendan Mulhern. As Shadfield nurses Leance back to health, a sinister air begins to steal into the confined quarters of the lighthouse. Both men, it transpires, are harboring terrible secrets. These come to light in a second act that, Orem says proudly, left one audience member declaring herself “shellshocked.”

Orem, currently Writer-in-Residence at Emerson College, is not interested in small talk. The first line of his biography gets right to the point—”William Orem (Playwright) writes about spiritual and philosophical questions.” In conversation, he is equally engaging and direct. “These are the questions that animate life,” he clarifies. “The ‘God’ stories we’ve always told are falling away. They might be inadequate cultural constructs, but they’re designed to answer questions that are still urgent. And a cynical stance avoids the fundamental questions of existence as much as any conformist religious outlook.” Discussing his work, he references Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams, Samuel Beckett, Ernest Hemingway, and Albert Camus with a familiarity that could seem casual if his reverence for their work, and desire to continue the conversations they began, weren’t so clear.

In the play itself, his language leaps from the technical to the lyric, expansive to terse. Against such verbal orchestration, every action and prop stands out with Chekhovian purpose. There are moments from The Seabirds that could be great paintings by Turner—a naked man hauled from a violent ocean, two loners gazing out to sea from a mist-shrouded tower, a noose silhouetted against a vast ocean sky.

The powerful realization of these moments is a testament to Argos Productions, the upstart company that brought the current version of The Seabirds to the stage for the first time. (An earlier draft was staged in 2007 at the Alleyway Theatre in Buffalo.) Argos’ founder and artistic director, Brett Marks, fell in love with the play years ago while reading scripts for the Huntington Theatre Company. “It’s like True West in a lighthouse,” he jokes. “It’s got these men—real men locked in this relationship and power struggle.”

Marks is humble about what Argos has achieved in its first two years, and about his own critical acclaim—he was named Boston’s Best Director in the Small/Fringe division by BroadwayWorld Boston, for his 2011 Independent Drama Society production of Glengarry Glen Ross. But he is clear and passionate about the company’s mission—serving playwrights as the true driving force behind plays. Marks originally set out to create “a space for my playwright friends, who were having a tough time finding productions,” to see their writing realized, “which is the best way to find how a play works.”

Argos prides itself on fostering a unique level of collaboration between the playwright and the other artists—directors, actors, and designers—whose job it is to realize his words before an audience. “Playwriting is the loneliest art in theater,” Marks muses. Acting, directing, even costume or set designing—all rely on creative dialogue. Writing, in contrast, is a solitary task.

In an attempt to reach across the gap, Argos invites writers to join every step of the production process. It thus offers “an opportunity for playwrights to see how other artists work—and artists not to be afraid of playwrights,” Marks explains. Many theater artists feel a combination of reverent fear and creative disregard for playwrights. Working on classics or Broadway hits, most never get a chance to speak with the dramatists whose words they interpret. Argos seeks to put the playwright back in the room, and in doing so, to “create a new vocabulary.”

In initial conversations with playwrights, collaborators identify “which ideas open our imaginations—make us want to run towards them—and which are ideas that we might be more wary of,” Marks explains. The work thus becomes “an education both ways.” Orem concurs. “What the play means to me is different from it as a working document. I can talk about the themes, but those are writer’s concerns.” If the company can stay true to the text, he suggests, then the fundamental questions of the work will come forth organically.

Argos also invites its playwrights to play a role in casting. Both roles of The Seabirds offer specific challenges. Leance’s force and energy—to say nothing of his Irish accent—require a unique set of skills. But when Orem saw Brendan Mulhern, he was impressed with the actor’s physicality. Mulhern’s extensive comedic experience—he’s performed at ImprovBoston for a number of years—proved an unexpected perk. “I didn’t realize the first act was so funny,” Orem admits. As for Shadfield, the writer explains, “The actor has to show someone not showing—the audience must see a mask, but not see it removed until the very end.” David Lutheran, an actor equally at home with comic and dramatic material, handles the task with aplomb.

Throughout the rest of the production period, Argos maintains a dialogue with the dramatist that is both critical and supportive. “We don’t change lines in rehearsal—playwrights do,” Marks explains. “We just pose the questions. It’s always up to the playwright to see the issues.”

Nor does this conversation end on opening night. Performances themselves can be potent tools for development. Orem describes the experience of sitting invisibly in the audience, noting reactions. Some moments land—in others, the rhythm is off. By listening and watching from amongst newcomers, the playwright can gain crucial insight on how his work impacts an audience.

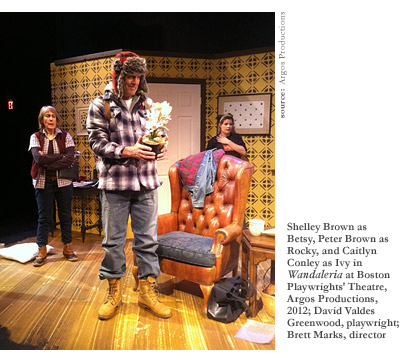

For a model in its second year of operation, the process has proved remarkably successful, both for Argos and for the playwrights it serves. “Working with Argos was excellent,” says David Valdes Greenwood, whose Wandaleria premiered at Argos in January 2012. “Brett Marks allows the playwright to be involved in the process from start to finish—from casting to closing—and he’s equally adept at asking and answering questions that arise in the process. I learned things about the voice of the play, what was clear and what wasn’t, during rehearsals, and more about the pace as the play went up onstage. It was a rewarding process entirely. Since then, Argos has made some introductions for the play and I have submitted it elsewhere with more confidence.”

This ongoing life is crucial to Argos’ mission. “How we pick shows has a lot to do with how we see them after our runs,” says Marks. “It’s not just the current life of the play, but whether it gets a second and a third production. We introduce other companies, locally and around the country, to plays that we support. It’s especially meaningful coming from a company that’s already taken a risk on the play.”

Risk is both an artistic and financial concern for a newborn theater company. “It’s hard to sell new plays,” Marks admits. “Audiences come out for what they know.” It’s the same dreaded equation of familiarity—famous plays trump the unknowns, and established companies have a clear hand over the upstarts. A new company devoted to new work is a bold endeavor indeed.

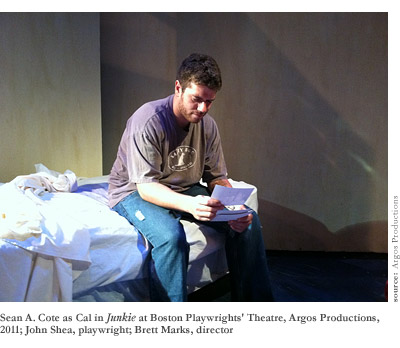

The first season, says Marks, was about building an audience. It’s perhaps no wonder, then, that the three plays selected—Valdes Greenwood’s Wandaleria, Catherine M. O’Neill’s Murph, and John Shea’s Junkie—were all contemporary, New England comedies. “We introduced audiences to three different works that they could connect to. I knew I enjoyed Seabirds, but it took some time for me to know how others would react.” Marks directed all three, leaving him, by his own admission, “a little burned out.” For The Seabirds, he turned the reins over to a trusted collaborator, Jeremy Johnson, whose work, especially in musical theater, has been seen and acclaimed around Boston. Marks’ own contributions to the production were both in the details—he choreographed the fight scenes and took charge of props—and, as artistic director of the company, in a broader guiding purpose.

Argos operates on modest budgets. “We try to take the essence of what the design demands,” Marks explains. Another mounting of The Seabirds might incorporate a full second level of the lighthouse, for instance. But lacking such resources, the Argos production “focused on the journey of these two characters.”

Not that the work looks especially low-budget. Shadfield’s lighthouse, skillfully recreated in Matt Whiton’s set, is full of nautical bric-a-brac. Gorgeous lights by Michael Clark Wonson play against the plain backdrop, creating skies for all weathers and times of day. In nighttime scenes, the roving illumination of the beacon cuts through the scene periodically, adding the suggestion of great height to the one-story set. Time and place are evoked clearly and carefully.

“Detail is key in a historical play,” Marks notes. Perhaps this is why historical drama is typically the purview of film and TV. Sumptuous costumes and grandiose battles lend themselves to silver-screen scope—and silver-screen budgets. Historical stories are necessarily epic, and plays simply don’t handle epic very well—at least not in modern theaters, wary of casts larger than four or sets that call for more than a couch.

Of course, this hasn’t always been the case. Playwrights from the ancient Greeks to the Elizabethans consciously set their greatest works in previous decades, allowing them to comment on the dilemmas of the present while dodging both censorship and narrow topicality. As plays have grown smaller, retreating from public issues and into bars and bedrooms, they have also found themselves caught in a narrow present. The Crucible, probably the most famous American play about a time other than the one in which it was written, is now sixty years old. The Civil War, the most defining of American conflicts, has produced numerous iconic novels, films, and paintings—and not a single canonical play.

But William Orem isn’t daunted by the paucity of predecessors. “I didn’t sit down and say I’ll be one of those guys who writes historical things,” he explains. Yet the dramatic questions he seeks to investigate consistently draw him back into the past. (His debut novel, Killer of Crying Deer, takes place in the Florida Keys in 1699.) For The Seabirds, he began with questions: What was the life of a lighthouse keeper like? What was it like to fight at sea during the Civil War? But engrossing as this research can be, Orem warns of overindulgence. The audience shouldn’t be “overwhelmed with data”—they should be immersed in the lives of people, who, like their modern-day counterparts, don’t often draw attention to the wider currents of history around them.

Why the Civil War? “In 1863,” he suggests, “the question is, what does it mean to be an American? Today, we are living in what the country decided it would be. And now—we are again the closest we’ve been to asking such fundamental questions about what this union means.”

It is fitting that Orem sees the past as ongoing challenge, rather than as artifact. Theater, after all, exists in an immediate present. This is certainly part of its challenge. “An audience can’t put a play down and get some lunch,” Orem notes, in contrast to a novel. The words pass by in real time—”actors say them, and they’re gone.” This “immediacy of live people,” as he puts it, is entirely the point. The play may exist in two forms, as the battle of ideas in the author’s head and the dance of physical presences onstage. But it is only the latter that truly matters in the end—the electric current from actor to audience.

Orem’s play isn’t experimental. It breaks no boundaries, forces no reconsiderations of art or performance. Instead, it makes a powerful case that effective new theater can simply be good, old theater. Historical drama isn’t dead. Having passed on pageantry to TV networks, it now has a remarkable claim on immediacy. Film is recorded, edited, processed—the past and present are filtered, and even the future has already happened. In theater, every moment is inescapable and current.

It makes perfect sense that The Seabirds has been on Marks’ mind since he started Argos. They are shaped for each other, in many ways—this unapologetically profound play and this sincerely ambitious company. Both have in mind a theater that goes beyond entertainment, and even beyond art for art’s sake. Theirs is a drama in which great things happen, to plays and to people. The faith that suffuses Orem’s writing is related to Marks’ belief in the power of writers to take back American theater. Neither are idealists. They know the odds, they doubt and they question. But they are determined to keep up the struggle.

When asked about his company’s name, Brett Marks is self-deprecating, almost apologetic. Yet his explanation is profound—and central to his vision. Argos, he explains, was the shipwright who crafted the Argo, the vessel that bore Jason and his crew of heroes on their quest for the Golden Fleece. In emulation of the legendary craftsman, he envisions his company as “the shipbuilder for the great heroes to help them go to the ends of the Earth. What we provide is opportunity.”