Time may be the most universal element of the human condition. It governs how we experience the world and remains life’s lone limited resource. Art couples two attempts to circumvent time’s oppressive march: by trapping single moments in frozen expression, and through the hope that the tangible products of that expression will communicate something to other humans beyond the artist’s own lifetime.

D.C. Kelley is, quite uniquely, an artist working outside of time. His new pastel, paint, and collage works constitute an unexpected addition to an evolving catalogue that remains invested in a private, painterly journey of Odyssean scope.

This March, Kelley contributed a magnificent set of prints to a group exhibition at the Soprafina Gallery in Boston’s South End. I described the etchings and woodcuts as “artifacts of the unknowable,” intimating their strength as physical objects and expressing the sense of transcendental permanence they communicated to the viewers’ collective unconscious. On September 7th, Kelley will mount his first solo exhibition in longer than the artist can remember, again at Soprafina, featuring startlingly new works in a range of fresh media. And while they are not quite beyond redemption, in general these new works do not match the mastery of his previous efforts.

The exhibition—which runs through September 29th following the opening night artist’s reception—marks an unexpected direction in a quixotic career that has never appeared on any radar but Kelley’s own. He is getting old, though no one seems to have told him. “For now I feel that life has just begun,” he tells me, and I believe him. The splendid isolation of age and obscurity remains, perhaps, his greatest asset and the lone force sustaining his relevance in an art climate whose changes have left him unable or uninterested in adapting.

Kelley’s latest works chart the odd bearing of this ambiguous position. Overwhelmingly populated by two numbered series—Cathy and Red Drawing – Lips—they reveal the artist’s now-governing interest in abstraction, a mixed, material sensuality, and the investing of color with form and pictorial weight. These are not original projects; Kelley is reenacting the painterly experiments of a bygone era. He is, essentially, working in the space between the end of abstraction—best characterized by Willem de Kooning’s and Jackson Pollock’s respective extrapolations of figure and ground—and the rise of Pop, particularly the ascension of assemblage artists Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. Consequently, the dialogue between Kelley’s personal development and the art-historical is more interesting than the works themselves.

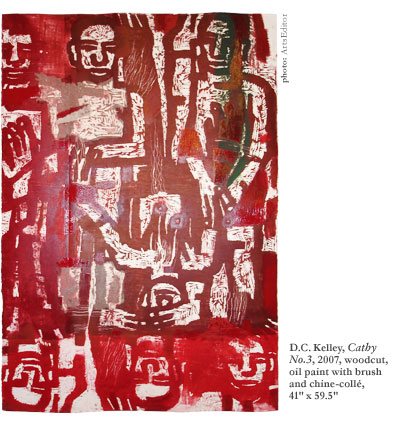

Cathy bridges Kelley’s recent projects, juxtaposing the totemic image-making of his prints with gestural expression and a raw material sensibility, articulated by layering chine-collé, pencil, oils, and mixed materials on top of his familiar, primitivistic woodcuts. His palette retains the earthy strength of simple reds and browns that characterizes his etchings, but the figuration has lost its coherence: Cathy No.3 is a hobbyist’s Frankenstein project, with two marginally related prints pasted on top of one another. Their noticeably unmatched coloration betrays an impulsive schizophrenia that finds confirmation in the arbitrary patches of masking tape that adorn works throughout the series, all without formal or aesthetic motivation beyond whim.

Even more confusing than the devolution of Kelley’s recent prints is his awareness of the control he seems to be losing. “That was a totally impulsive movement, which is in a lot of cases the way in which I work,” he says of Cathy No.3‘s fragmented composition. “There is something in all of these woodcuts that isn’t quite mastered.” Romantic though the muse may be, no man is not the master of his own works. Kelley has clearly shifted gears, exchanging his impenetrable plasticity for a record of his emotional experience—he has become an artist of the ephemeral.

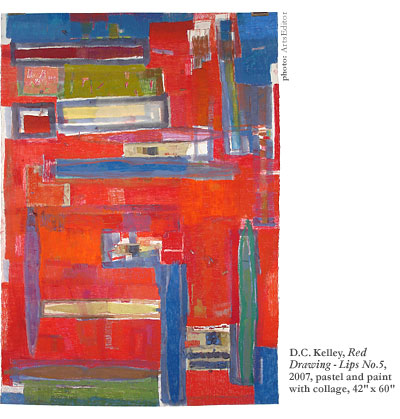

Kelley’s “vague feeling that the [Cathy] project has ended” reaffirms the eschewing of his past works, which develops clearly throughout the Red Drawing – Lips series. Foreshadowing a new direction, the Lips echo the abstract expressionist’s casting-off of painterly stability and establish gesture painting and collage as essential touchstones for absorbing the new trajectory of Kelley’s career.

Operating on no terms but his own, D.C. Kelley has advanced. “I’ve made a breakthrough by combining paint and pastel, and I need it to keep moving forward.” He is a living iteration of Jorge Luis Borges’ character Pierre Menard—a fictional modern author who “recreated” Miguel de Cervantes’ 17th Century novel Don Quixote word-for-word without ever having read the original—and his breakthrough offers a curious perspective on both his private odyssey and the reinterpretation of a static movement (Abstract Expressionism) in a vastly different and changing cultural moment.

Red Drawing – Lips No.5 is, according to Kelley, a formal exploration. “All my work is figurative,” he claims. “Even the most abstract lips paintings are figurative projects for me, projects about the problems of painting. The abstract pushes forward and becomes the visual object.” Those last words could describe a classic Rothko, and if Kelley released his shrouds of color from their figurative mandate, the so-called lip forms could be a point of departure from which he could approach the sublime subject matter pursued by his metaphysical contemporaries—tragedy, ecstasy, doom.

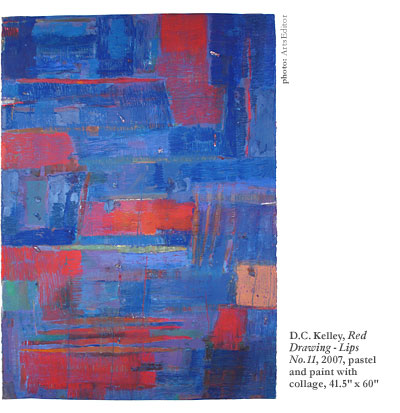

Visually, Kelley has already begun to embrace that direction. Heavy texturing throughout the series, especially in works such as Red Drawing – Lips No.11 (a predominantly blue painting), yields a pictorial space that breathes, allowing the figures to move in and out of the paper’s visual plane, evoking a subtle rhythm among swatches floating in various stages of abstraction. The Lips exhale a swampy, pastel breath into the environment, and you sense a tactile tension hanging among the unframed drawings. The paper media tempt the most intimate inspection, and the dense, chalky color fields that haunt their surfaces express moving transience and ephemerality. Their fragility underscores the presence of the artist’s hand and the experimental upwelling of emotions that it traces across the paper canvas.

The Lips do not, however, stand up to more incisive criticism. The same fragility betrays an undisciplined stab at an unintentionally ambiguous expression. No order guides their internal composition or formal elements, and the wildness is not instigated chaos but the loss of control that invariably accompanies new and experimental projects. There is something redeeming in the deliberately crude application of mixed materials that expresses the decay, despondency, urbanism, and poverty—be it concrete or spiritual—that characterizes the works of Jean-Michel Basquiat or Jacques de la Villeglé, but Kelley’s motivations are neither so thoughtful nor self-involved. This, again, leads us to the fertile oblivion of Kelley’s quest.

Most artists do not take age—the experience of time, and the mark of their mortality—lightly. Seniority is associated with irrelevance, impotence, and decline. In 1984, Steve Jobs quipped with snide poignancy words that align themselves with both popular conception and empirical truth: “It’s rare that you see an artist in his 30s or 40s able to really contribute something amazing.” Jobs was twenty-nine at the time, and on the crest of Apple’s great breakthrough. Notwithstanding, two decades later—to say nothing of several failures—Jobs himself pioneered the triumphant innovations that revitalized his company and solidified his brilliance and artistry.

Though he may be reliving the life of another 20th Century luminary, D.C. Kelley is not Steve Jobs. His copper plate prints emit extraordinary presence, but he has twice passed his 30s and 40s and his latest works reveal the inconsistency of his taste and the frailty of his sensibility. Despite all of this, though, Kelley remains an artist operating with fearless autonomy as he helms the voyage of another generation’s artists in his own time.

In a lesser sense, Kelley offers a younger generation the opportunity to experience new creations in the spirit of last century’s most influential contemporary art movement. Wherever he—our self-described “restless prostitute”—turns next in his lonely journey will be of great interest. “I’m thinking about further surfaces and layers that could be extended out from the canvas,” he tells me, and I can’t help but imagine him experiencing Allan Kaprow’s monumental leap from ephemeral collages and environmental constructions into Happenings and performance art. In another, greater sense, though, Kelley is an artist that has committed himself to the journey of a lifetime, and each advancement he makes is another triumph for the individual spirit and its power to compel us past our isolation, in its own moment and beyond.