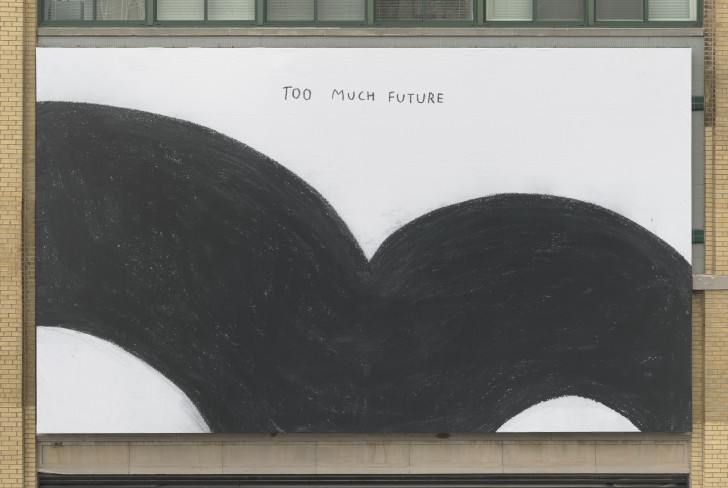

Leaves rustle as they are swept into a cyclone. Laughter and excitement emanate from the voices of students on a field trip down the block. The dull, constant, drill-and-whirr of machinery against metal down the street contributes to the sound of an impromptu orchestra. This is the music that is often taken for granted—and that is the focus of Too Much Future, a public artwork by deaf sound artist Christine Sun Kim, on view as part of the ongoing series of public installations located across the street from the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Kim’s work grapples with the outsider status of being non-hearing in a hearing world. This makes her works hyper-focused on all sounds, many of which are otherwise missed or ignored by the hearing world. Kim’s disconnect manifests in what she calls “sound etiquette”. Various actions go unnoticed by Kim—such as excessive silverware to plate contact or pressure on a blackboard—while however, the same scraping of metal or screeching of chalk may cause severe discomfort among the hearing. After spending her whole life trying not to cause such annoyances, Kim’s artistic mission is “unlearning sound etiquette,” which opens up a broad realm of possibility for her works to explore—including Too Much Future.

Although her works use sound as a primary medium, she began her career with a visual focus, after completing her MFA at the School of Visual Arts. Post graduation, she went on to pursue a degree in Sound and Music at Bard College, where auditory media overtook her oeuvre. Originally from California, the New York City-based artist was raised by two hearing parents and one deaf sister, and since completing her educational tour-de-force, Kim has carried out a residence at the Whitney Museum, exhibited work at MoMA PS1, and was recently made a TED fellow.

Kim’s works have evolved to include sound as both a conceptual and literal expression. In Game of Skill 2.0, participants concentrate on comprehending a distorted voice that lectures on the future, only audible through an apparatus of Kim’s creation. The words become audible once the device is held correctly, challenging the participant to acknowledge sound critically. In a installation titled What Can a Body Do?, Kim places blank panels onto a speaker that roars and shakes violently. She then deposits paint onto the surface, creating volatile splashes and drips, manifesting visually the machine’s sound and motion. Too Much Future falls into the latter category, a visual piece that engages conceptually with sound, without actually utilizing sound—as when the paintings suggest the buzzing of the unheard motor.

To a hearing person, it may be puzzling how the work relates to sound at all: ultimately, all Too Much Future consists of is a large rectangle that hangs directly across from the High Line, an elevated linear park in Manhattan. From a distance, it reads as a billboard, and could almost be confused with a black and white golden arches—an eerie, dysmorphic McDonald’s logo. But closer up, the work is legible, with two magnified charcoal lines playfully scrawling the title in small text above.

The only way to contextualize the work as a “sound piece” is by drawing on the literal symbolism of American sign language, a common motif in Kim’s work. The American sign for “future” is made by raising a flat hand to the temple and extending it downward, the path of motion suggesting an arc. If the speaker—or rather, signer—is implying a more distant future, two hands may be used—a double arc, as also traced out by the lines of Kim’s piece.

As the arcs are cropped from the frame, they suggest a sense of infinite arcs, a visual demonstration of excessive future. Yet the double arc visible to the viewer is black, smudgy, and dense—not the precise, effortless sweeps of paired hands signing. Perhaps this suggests a darker, more ominous future that is harder to understand, more difficult to engage with. Or perhaps the fuzzy, forward-looking gesture towards the unknown is meant to invoke a dualistic sense of messy script: childlike and playful on one hand; fearful, neurotic, and frantically warning on the other. Indeed, the piece’s greatest allure may lie in the fluidity with which it invokes playfulness and ominousness in tandem.

Playfulness is highlighted in several of Kim’s other pieces, all drawing from the sign for “future”, and all completed in charcoal. Future Gets Paranoid has an alarming dip, coupled with some actions lines. Future Schmuture flattens out after the first arc. Good Grief Future is more of a zig-zag than arcs. Arguably, the most humorous is an arc that doesn’t resurface as it lands itself as a hole-in-one; this golf tournament is entitled Future with White Privileges. Despite exploring something as daunting and unknown as the future, Kim consistently demonstrates her cheeky sense of humour with these subtle but ensnaring flourishes.

Some insight may be gleaned from considering the context Kim likely wants the viewer to adopt in contemplating the future. Like many Futurists, Kim is concerned with motion, time, and technology—is Too Much Future a warning, the changes wrought on sound and communication in a digital age? Such a position would stand in smart dialogue with Kim’s personal cannon, within which she has tackled the impeding forces of technological advancements and their influence on communication—for audiences of the deaf as well as the hearing.

It’s unclear if Too Much Future should be read in the context of how verbal and non-verbal communication alike are changing in a world were the driving force is technology. Without background, there is only so much one can reliably untangle from its vague and cryptic message. The only thing that is truly clear is that Too Much Future is a protest; a dissatisfaction with the current affairs of the world, and a desire for them to halt.