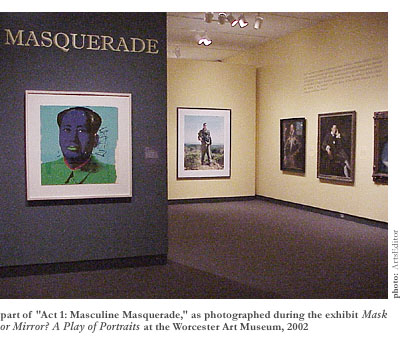

In an intimate corner at the front of the large gallery, artistic renderings of several earth-shaking men—alpha male muck-a-mucks or “great men” who did what had to be done?—wait silently on walls and pedestals to greet you to Mask or Mirror? A Play of Portraits, on exhibit at the Worcester Art Museum through January 26th.

To get to them, you forestall the pleasure of looking into the ruddy face of a friar (painted by Goya) and the fair features of a scholarly Boston merchant (painted by Copley). Hoping to ground yourself in the obscure pieces first, you also pass the modern ironies you’re a little tired of by now—a purple-faced print of Mao by Andy Warhol; a life-sized photo of a wax statue of Yasser Arafat by Hiroshi Sugimoto—and walk right up to the cameo stone relief of the Egyptian pharaoh Ay—lifted from a wall of his tomb, says the caption—depicted in his humble beginnings as a fan-bearing servant.

You turn to confront, in the name of justice for all proletarian fiddle-makers, the broad-faced marble bust of the brutish Roman emperor Nero, nose justifiably smashed in a fall to some other museum floor. And tilting back your partly informed head, you squint into the faded framed portrait of Aurangzeb, last of the majestic Indian Mughals, hobbling across a featureless green 17th Century landscape with a cane in his dotage, head bent in regret for the cruelties he inflicted on people in the name of old-time Islamic religion, lemon-yellow head-scarf and blouse not lovely enough to lighten his mood.

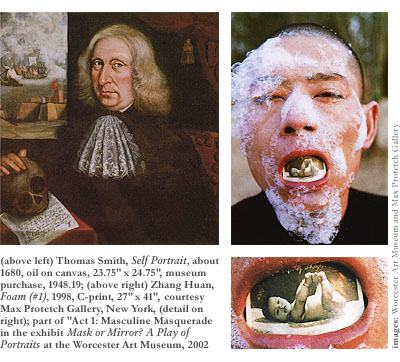

You leer at that maniac Napoleon, pompously pretty in a large black and white print, nod to the grumpy-looking gallery guard (whose grandpa’s portrait probably doesn’t hang among these men of power), and turn the corner to see—heaven help us all—a huge photo of an East Asian man with eyes partly closed, mouth wide open, and foam all over his face. Foam—of shaving cream, saliva, sea-scum, or something—encrusts his chin, nose, forehead, and his black burr haircut (which matches his black shirt). To make matters worse, there’s a baby in his mouth, or a photo of a baby maybe—but a happy-looking baby it is, peaceful as can be, lying on his back, holding his toes, and turning his head our way. A bitter ode to Wordsworth or Piaget.

You can’t help but stand back in wonder. Is the agony of the foam-man due to the psychic pain caused by his obligation to the inhabitant of his oral cavity? (If he closes his mouth, the kid’ll probably suffocate.) Is it due to the memory of a child’s enchantment that he no longer can muster? To his inability to speak while the baby’s using his tongue as a diaper-changing blanket? Or is his agony due to the oppression of being displayed on the same wall as the self-portrait of gray-haired, beruffled, colonial American-Puritan painter Thomas Smith, who, seemingly unfazed by the freaky photo next to him, gives us his steady gaze from a dark Boston room in the 17th Century, his right hand resting on a symbolic skull that acts as a paper weight for a cursive poem about the “world of evils” that, ironically, finds profitable representation in the illustration of the merchant ship behind him on the wall.

That’s enough of that. You’ve seen some 28 portraits of men in the exhibit by now—fantastic stuff by an anonymous Etruscan carver of cinerary sculpture, photos by Mathew B. Brady and Rineke Dijkstra, oil painting by Chuck Close and the late Massachusetts painter Gregory Gillespie—and you’re only a quarter of the way through the exhibit!

Crossing an invisible border where the section of the exhibit titled “Masculine Masquerade” gives way to “Who Is She?”, you wonder if some of the testosterone-induced excitement will die down with the sudden absence of dominant male figures you just love to hate. For name-dropping purposes, there’s just a Warhol lithograph of lady Liz (to complement his male Mao) and an Imogen Cunningham photo of Gertrude Stein—female American icons of aesthetically divergent influence to say the least. You’re not likely to recognize Marcus Aurelius’ daughter in one ancient Roman bust the way you might have Nero back at the entrance. You might have recognized Napoleon pouting in his drawing room back there, but you wouldn’t know the 16th Century Queen Eleanor of Austria (painted by a Flemish artist you’ve never heard of) from Eve. And only if their portraits hang in the hallway of your Mt. Vernon St. mansion would you know that those two colonial American women over there are Ann Gibbes and Mrs. Perez Morton, the former painted by John Wollaston whose beach you’ve been to in Quincy, the latter by Gilbert Stuart, whose paintings of George and Martha you’ve seen at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. And who posed for those paintings by celebrated American-born portrait painters Thomas Eakins and James A. M. Whistler? No telling who they are, either.

Sometimes it’s good not to have preconceptions about art anyway. You go to the sleeper movie of the year, made by an unknown director and starring some surprisingly good unknown actors who won’t be typecast for at least another year; or you read a completely wonderful poem in a small literary magazine by someone who hasn’t even published a book yet.

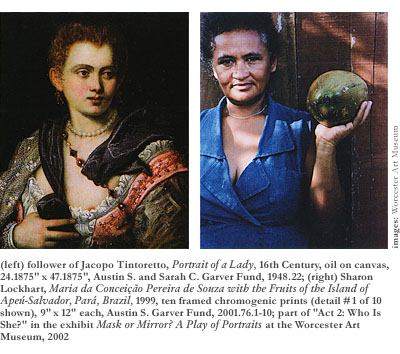

Cindy Sherman’s photographic self-portrait masquerade as a ditzy blonde wannabe starlet; Walter John Knewstub’s florid oil portrait of a ravished redhead Victorian; an anonymous 16th Century French portrait of a pale aristocratic woman at her toilette; Catherine Opie’s bold color photo of a punked-out and tattooed artsy-looking lesbian chick. As the contrasts keep on coming, spanning the overwhelming present and the distant past that the contrasts make mysteriously more imaginable, you feel yourself expanding to admit the multitudes. Where else but here could the bust of Marcus Aurelius’ stately daughter occupy the same room as a photo of a lazy-looking, couch-potato woman reclining on her cheap brown sofa in a gaudy floral housedress and blue moccasins, arms behind her head like some Okie odalisque? Where else could a Portrait of a Lady (by a follower of 16th Century Venetian painter Jacopo Tintoretto) share personal space with a gathering of 10 photos of a turn-of-the-millennium Brazilian woman named Maria da Conceição Pereira de Souza? It helps to know that this Venetian lady, luxuriously decked out in pearls, ruffled underblouse, amber necklace, and droopy earrings, worked a double shift as poet and prostitute in the commercial crossroads of the world. (Despite a feminine masquerade that also includes exposed left nipple, cupidic lips, and rosy cheeks, she has the pinched face and short red haircut of a teenage boy.) And it doesn’t hurt to know the names of the 10 ripe tropical fruits that the sensual, 50ish Brazilian woman of her day—in a photo taken by Sharon Lockhart, of Norwood, Massachusetts—holds up in her left hand, either, one fruit per photo (coco, ajirú, murici, cajú, mamão, tucumã, taperebá, goiaba, tamarino, and graviola). In a blue dress unbuttoned to reveal a soft expanse of creamy brown flesh, her handsome brown masculine face works with her buxom beauty and fruit display to suggest fecundity. She’s nothing less than a fertility image.

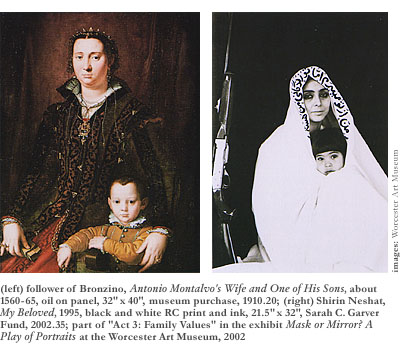

The invisible border between “Who Is She?” and the third thematic “act” of the exhibit, “Family Values,” is much less conspicuous. Elegant old upper-class drawing-room images of precious children by Thomas Gainsborough, Cornelis van der Voort, and John Singer Sargent. An atmospheric Victorian photo of beautiful British children by Lewis Carroll, author of Alice in Wonderland. That famous black and white photo of Identical Twins, Roselle, N.J. (identically doleful little girls dressed up for Saturday prayers at the temple, perhaps) by late New York bleak-is-beautiful photographer Diane Arbus. And variations on the classic Madonna-and-child theme: a bold, life-sized nude photo (by Renee Cox) of an athletic African-American monument of a woman holding across her strikingly vertical, highly polished brown length a lighter-skinned child at a horizontal angle that puts you in mind of the composition of a cross. Another black and white photograph, titled My Beloved, by Shirin Neshat, of a dark-eyed, olive-skinned Arab beauty enclosing within her bright white shroud of a dress her beautiful, unscathed child, his brown bangs and dark eyes protected from a harsh world that is represented by a rifle leaning at a conspicuously topical and vertical angle in a corner of the picture, the elliptical opening of her head-covering dress allowing you a peek into the warm and earthy womanhood that men with guns cannot get back to once they have left the arms of the mother. (The little boy in Antonio Montalvo’s Wife and One of his Sons, a painting by a follower of Italian painter Bronzino, hasn’t had to leave his mother and go get his gun either. Why would he ever?)

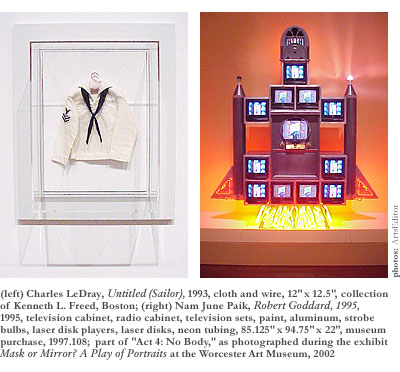

There’s no need for a border between “Family Values” and “No Body,” the fourth and final part of the exhibit. Offering comic relief from and hopeless resolution of the three previous acts, the latter’s predominance of conceptual installation art is so frivolous by contrast with the tragic relief of the rest of the exhibit that the walk through a doorway and down a hallway seems almost not worth the effort. Nevertheless, it’s good to see Charles LeDray’s little sailor suit, a vintage toddler’s uniform hung on a cushioned coat-hanger in a Plexiglas case, if only to shiver at the thought of boys being trained to be like the military monsters in the masculine masquerade. On the other side of the gender divide, Eleanor Antin’s Naomi Dash, featuring towel rack, kitty-litter box, black sheer stockings, and pink bathing cap, speaks for certain female roles (sexually objective at best) that still wait to be played.

Though it doesn’t take long to look at this room, it does give you a well-deserved giggle in payment for the patience you have shown in your progress through the galleries. With a sense of relief that the “play of portraits” is over, you look at Nam June Paik’s three-dimensional techno-sculpture of physicist (and Worcester native) Robert Goddard, featuring several video monitors arranged to represent both the symmetrical setting of a rocket on a launching pad and the form of a person. It’s a fairly facile sardonic comment on the stereotypical space-cadet scientist: a witheringly rational control-freak robot. No use looking much longer at it than it takes to get the good giggle. The monitors flash continuous, indiscernible images in blue and green, and a red and yellow neon representation of fire at Goddard’s feet assures you that you don’t have to be an art historian, nor a rocket scientist, to get a kick out of contemporary art.