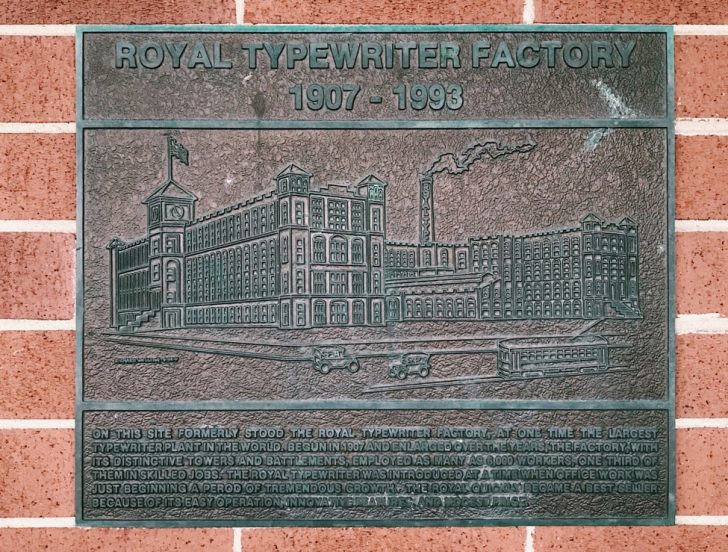

On a grey day in January 2019, covered with layers of clothes, I ended up standing still in the parking lot of a supermarket in Hartford, Connecticut. I’d just traveled thirty-five thousand miles to see the remains of the factory where eighty-nine years ago, the typewriter I bought at a flea market in Paris was built. A memorial plate told me I was at the right spot:

“On this site formerly stood the Royal Typewriter Factory, at one time the largest typewriter plant in the world. Begun in 1907 and enlarged over the years, the factory, with its distinctive towers and battlements, employed as many as 6000 workers, one-third of them in skilled jobs. The Royal Typewriter was introduced at a time when office work was just beginning a period of tremendous growth. The Royal quickly became a best seller because of its easy operation, innovative features, and modest price.”

There was nothing else to see and I knew it before planning this trip, but I had to go. It all started a few months before, at rue du Poteau, in the 18th district of Paris, on a sunny late fall Sunday, a perfect flea market day. Dozens of sellers were preparing to sell thousands of items to hundreds of buyers. Everybody thought they’d get something out of it. Some would get rid of cumbersome things, others would bother with useless things. It was a natural process, an eternal cycle in which everyone participated with varying degrees of goodwill. And, at the next sale, the roles would be reversed.

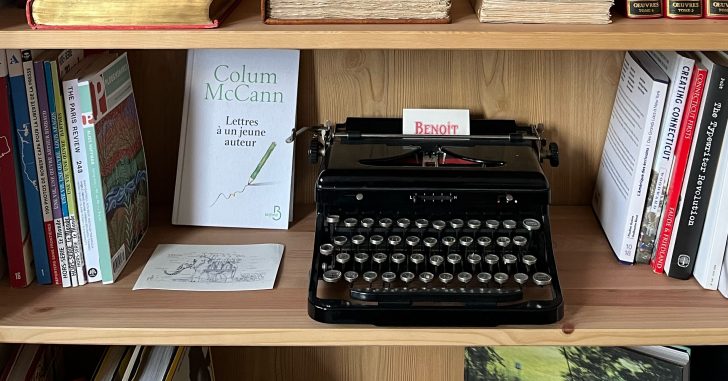

On that day, I was on the buyers’ side. For several months, I was looking for a typewriter to decorate my bookshelves, a thinly disguised nod to those writers from another century that I admired. In vain. Of all I had seen, none had aroused in me the nervous excitement that one feels when buying something not out of need, but out of envy. As I walked through the crowded aisles of this flea market, I realized that I had no idea what this machine was supposed to look like. I was not one of those fetish collectors who wanted to acquire a relic of a famous artist. Or a savvy connoisseur with a nose for bargains. I had only two criteria, rather sketchy, that it be beautiful to look at and cheap to pay for.

At the crossroads of the rue du Poteau and the rue Duhesme, on a booth delimited by marks of fluorescent spray paint, it was there, on a wooden plank supported by trestles and covered with a white sheet, between a set of old-time video games, copper pots, and dust traps. I don’t remember the man it belonged to. What I do remember is that he assured me that it was in perfect working condition—his father had finished restoring it in recent weeks—and that he was selling it for 60 euros. Even though it didn’t look rare or original, I liked it right away. It was discreet and refined. It would blend in well with the set of my living room’s apartment. So I turned my back on the salesman and left. It wasn’t until late afternoon, after dithering for hours, cursing myself for not having been able to make up my mind earlier and falling into despair at the thought that I would never see it again, then I was back to close the deal. In the meantime, the price had dropped by 10 euros, and I went home with her suitcase under my arm, happy to have made a deal and unaware of what this purchase would involve.

Over the next few months, my typewriter remained on the shelf where I had left it when I came home from the flea market. From time to time, I removed the dust that accumulated on its metal casing and took the opportunity to randomly type on the keys of the keyboard, but my interest in it seemed to have disappeared the moment I owned it. Then, one day, while I was still going through this routine, I wondered how it got here. This machine was a survivor of an era that seemed abstract to me, like all the eras that we have not lived through, and the way it had passed from hand to hand to reach my home was a mystery, a confluence of improbable circumstances. Now that our fates were linked, I needed to understand what had happened. I placed it on my apartment’s floor, right in front of a window, looking for the slightest clue that would allow me to retrace its path or, failing that, to imagine it.

Here is what I found out: the brand, Royal; model, Standard Portable (also called Model O or Touch Control); manufacturing date, year 1935; manufactured location, 150 New Park Avenue, Hartford, Connecticut. I had a lead.

Hartford. I’ve never heard of it before and if I had had to place this city on a map, the sound of its name would have led my index finger to an English countryside, very far from its real location, between New York and Boston, along the Connecticut River. As soon as I began my research, I realized that Hartford, in addition to being the capital of the state of Connecticut, was Atlantis: a myth of American history overwhelmed by the wave of progress and globalization. After the Civil War, Hartford was the richest city in the United States. Today, it looks like those sunken villages with only the church tower on the surface of the water. Its decline, like its rise, was spectacular. For a long time, it was above all unimaginable. Because in Hartford millions of typewriters were assembled by Royal, Remington, Underwood and dozens of other manufacturers; electric and gas-powered cars, bicycles, guns, sewing machines, clocks and tools were produced in industrial quantities for decades; Hartford was also the insurance capital of the world, a title acquired at the expense of New York after a huge fire in 1835; Hartford was the home of Mark Twain, one of America’s greatest writers, Harriet Beecher Stowe, the author who achieved considerable success with “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”, Noah Webster, the man behind the first American dictionary, and Samuel Colt, the inventor of the revolver of the same name, who set up his business there; Hartford was the home of the first American bicycle, invented and manufactured by the Pope Manufacturing Company; Hartford was the site of the first radio transmission from an airplane; Hartford is the home of the oldest continuously published daily newspaper in the United States since 1764, the Hartford Courant; Hartford is the site of the oldest public art museum in the country, the Wadsworth Athenaeum; Hartford is where George Washington and the Earl of Rochambeau, joined by the Marquis de Lafayette, met on September 20, 1780, during the Revolutionary War; Hartford is where Alse Young, the first person to be convicted of witchcraft in the colonies, was hanged in 1647, a few years before the Salem, Massachusetts trials; Hartford is where financier J.P. Morgan, the writer Jay McInerney and the actress Katharine Hepburn were born.

For Hartford, Connecticut, this golden era ended when manufacturing activities started to be relocated abroad, causing an immense loss for many cities in the United States. Between the 1960s and the early 2000s, Hartford lost about forty percent of its population, most of its industries, and its aura. The town fell off the radar and the remnants of its greatness were gradually destroyed. This is the fate of the Royal Factory, once a national monument, before it was abandoned in the early 1980s and ravaged in 1992 by a fire that everyone in the region remembers. Today, the site is occupied by a Stop & Shop supermarket. Looking at my typewriter, I had the impression that I was looking at a bottle returned from the sea. After crossing an ocean and several decades, it had just washed up in my apartment and the treasure map it contained was still intact. Looking at it, unfolded in front of me, I had only one thought in mind: to throw a notebook, a tape recorder, and some clothes into a suitcase and go in search of its sender. And I did.

Walking in the empty streets of Hartford filled me with an irrelevant melancholy for an era I never knew. The old abandoned diner on Farmington Avenue, the falling apart houses spread out in the city, the rare traces left of a glorious past… As I was walking through the neighborhood of Parkville, around the former Colt factory, or in Mark Twain’s house, I realized this experience was not how I imagined it. Not that I had something specific in mind, I was just curious to see where a random quest you fall into can lead you. It brought me the joy of adventure, digging in archives, meeting people from the past, and hearing stories they probably told hundreds of times for the first time. It also showed me how a vibrant place can disappear within a few decades because of progress. The need for evolution feels less urgent when people are left behind. Especially when we know the heritage we owe to typewriters. From a fancy and unpractical object, the Sholes and Glidden from 1874, that Mark Twain owned and hated, to an electric and stern machine, the IBM Selectric introduced in 1961, only a century passed. Today, we all write on polished, metal, multitask devices because of them. I don’t know if they need credit for this legacy, but being aware of this past made me realize the urge to slow down. What is wrong with single-tasking? We made it until the twentieth century by doing so.

Last but not least, the as-found Royal typewriter brought me a new home. Two years after this trip, I moved a few miles away from the former factory. I never went back though. I had a Stop & Shop closer to my Hartford apartment then and reside now closer to Boston in Mass. Whether lost in a garage or lying on a shelf, typewriters, despite the dust or the rust, just like any old stuff, are here to stay. They have stories to tell and new ones to inspire as long as you are up for a little change in your life.