Despite the most recent medical breakthroughs and holistic advice, the cure for what ails you may very well be found in a gallery setting. The scope of the exhibit Pulse: Art, Healing, and Transformation, on view from May 14th through August 31st at Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA), includes the work of fourteen international artists who explore, heal, and transform by virtue of their chosen media. For those who subscribe to Joseph Beuys’ cult-like following, you’ll be happy to know that numerous artists sharing in the moral dimensions of his oeuvre have been traced and collected here. The exhibit also takes as its starting point the work of Brazilian artist Lygia Clark, whose approach to healing promoted the therapeutic handling of relational objects, inspiring further generations of artists to overturn the subject/object opposition and diminish the traditional role of the art “object.” Beuys’ and Clark’s differing approaches to the malaise that affects art, individuals, and society are furthered and questioned by their inclusion.

German artist Joseph Beuys (1921-1986) tirelessly produced a torrent of objects, performances, and pronouncements during his career. His expanded concept of art emerged when postwar society’s aesthetic dimension was seemingly discredited by the horrors of recent history. For Beuys, the role of the artist is to heal the ills of our ailing humanity. His approach to art was to include all life in it and likewise infuse life with the rules of art. This “universal appropriation” straddles the domain of shamanism, a category to which the repertoire of Beuys often refers. It is not necessary, however, to accept this notion of artist as shaman to be completely enthralled by Beuys’ work or the story that launched his legacy—his reputed rescue by Tartar nomads in the aftermath of a plane crash during his service in the Second World War.

There are better things to do at the ICA than question Beuys’ mythical status—one can instead question the relative insanity of his very first American artistic happening, Coyote: I Like America and America Likes Me. I was delighted to find the video documentation of this project as part of the exhibit, a 37-minute window into the bizarre 1974 performance. For the project, Beuys was delivered via ambulance to René Block gallery in New York City, which served as a caged-in room where Beuys conducted three days of wordless dialogue with a coyote. Beuys was equipped with numerous symbolic objects (a copper cane, gloves, a flashlight) and was wrapped in a blanket of felt. Fifty copies of The Wall Street Journal were delivered each day of the project and used as litter. Beuys performed a series of various ritual gestures in order to channel the animal’s chaotic energy in an attempt to harmonize through it. The evocation of trauma and suffering as cathartic elements is rigorously employed in his work. Mostly the video captures long sequences of the coyote tearing strips of felt off the artist’s shroud, making for a wonderfully energized performance piece by the coyote, if nothing else.

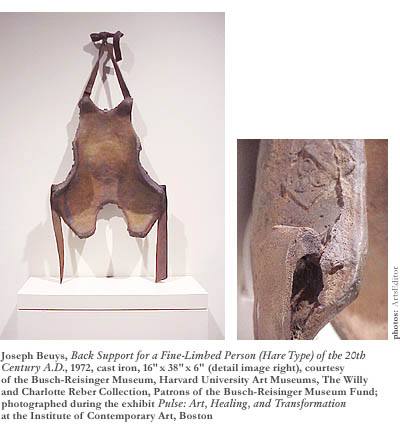

Beuys was known to favor the indecent and the ugly over the polished and the tasteful. The material syntax of his sculptures were properties of his favorite materials—grease, copper, felt, iron, and wax. Also displayed in this exhibit is Beuys’ cast iron Back Support for a Fine-Limbed Person (Hare Type) of the 20th Century A.D. (1972), reflecting his interest in the symbolism of different metals. Beuys was attracted to iron’s ability to slowly accumulate energy. By incorporating iron into the cast, the back support is transformed into an image of power.

In general, marking Beuys as a “starting point” for this exhibit remains a daring proposition. Although the influences of Beuys are easily found in the first generation of modern performance artists, his sculptures are arguably esoteric in nature and aim to liberate the energies of the spectator so as to procure an inner transformation, part and parcel of the transformation of society. The ICA’s ambition to locate other artists whose work might suggest similar ambitions of healing and transformation is a very tall order. Their success lies in presenting an incredible array of work by renowned international artists, all with shared concerns of healing.

To add to the bite already perhaps too big to chew, the artistic oeuvre of Lygia Clark (1920-1988) is a frightfully difficult challenge for any curator. Her works post-1965, labeled “propositions,” were never intended to be saleable or shown. Pedra e Ar (Stone and Air) is a simple pebble placed on an air-filled plastic bag and represents the sort of work intended for touch, movement, and play. Respire Comigo (Breathe with Me) is an industrial rubber tire that mimics the sound of breathing when manipulated. Clark’s mask series, Máscaras Sensoriais, is also displayed in the ICA exhibit. Wearing each mask brings about a different sensory experience, playing mainly with sight and sound. Sensorial phenomena address what she considered to be the malaise of the institution of art—the knot that binds the object to the market. Illness is the assignment of a specific value to an object, thereby alienating it and making it commercial. Healing is the forgetting of such illness. Clark insisted that her relational objects, on the other hand, only acquire specificity when in contact with the fantasies of her patients. In the early 1980s, her own health deteriorating, Clark began training psychologists and psychotherapists in her methods.

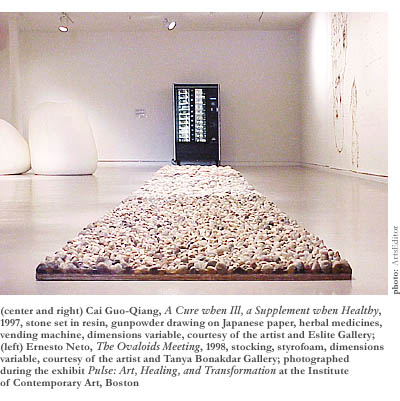

Ernesto Neto, whose work The Ovaloids Meeting has managed to become the visual motif for the exhibit, most clearly furthers the artistic territory defined by Clark. Neto’s minimal sculptures are human-sized, white lycra forms filled with styrofoam pellets. Each Ovaloid includes orifices for slipping one’s arms into in order to experience the sensation of the pellets and the strangely comforting embrace of the anthropomorphic forms. (Beanbag-esque, but don’t quote me.) Certainly the intent and the inversion of the art-as-object mimic Clark, and yet the Ovaloids are successful in a gallery setting, whereas Clark’s objects—almost spooky and unnerving—are riddled with je ne sais quoi.

A better voyeur than participant, the effect on me was a “why-am-I-hugging-this-thing-in-public” feeling, and its experiential qualities were better served from a distance watching the emasculating event of people disappearing into what look like giant white marshmallows. The physical and intellectual interaction Neto’s Ovaloids call for is playfully achieved, however, and my disdain for publicly embracing them is no fault of the artist.

After a brief break in the lobby, I felt ready to truly engage in something. Always drawn to the work of Cai Guo-Qiang, I took off my shoes. A Cure when Ill, a Supplement when Healthy (1997) combines the elements of traditional Chinese medicine, reflexology, and western consumerism. Visitors are encouraged to walk barefoot across a stone path that has varying sizes of stones arranged from small to large, leading to a vending machine that dispenses five different medicines for various ailments. On the wall to the right, the stone path is accompanied by hanging diagrams of reflection points on the bottom of the feet, each point corresponding to the health of a specific organ. These gunpowder-and-ink drawings are true to Cai fashion, earth-toned and harmonious yet peppered with the dramatic abstract effects of ink and powder on paper. Each mark seems both purposeful and accidental, wonderfully soothing as I prepared for the walk of unexpected pain.

I overheard someone comment that relatively healthy people won’t find the stone path painful whatsoever. After completing the short walk and almost biting my tongue off from the excruciation, I reread Cai’s maps for a prognosis of my evidently poor condition, suddenly less concerned with their aesthetic measure. Then again, pain is pleasure, and I felt compelled to walk the plank twice more before leaving. The effects are intended to be therapeutic, as are the tonics in the vending machine, and several turns on the path are recommended.

It is difficult to think of an exhibit that incorporates a comparable kaleidoscope of media. Hosting everything from architectural aluminum slides to cross-stitch, this ICA exhibit allows otherwise alienating media like video art to feel right at home. This is, after all, the institution that helped launch Bill Viola’s career.

An adept use of movement, improvisation, and inspiration is Still/Here, a fusion of dance, music, song, and video by dancer and choreographer Bill T. Jones. HIV positive himself, Jones wanted to create a dance that was part personal expression of living with a life-threatening illness and part universal representation. Fourteen “Survival Workshops” were organized in which participants shared their stories of grappling with serious illnesses. Gretchen Bender, a media artist, videotaped all the sessions, documenting the material Jones would eventually use to influence the choreography of the final piece. Dancers assume characters from the workshops, taking on their stories without impersonation. Still/Here is a strong moving portrait, well expressed and beautifully captured, making an emphatic statement about the pursuit of living.

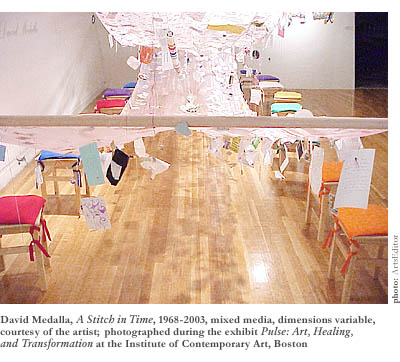

A Stitch in Time, a “participation-production” piece by Filipino artist David Medalla, allows any viewer to be an artist. This is not “every man is an artist” as Beuys had meant it—man’s social and political action becoming “social sculpture” and aiding the utopian vision. This is a literal manifestation of art’s universal ability to give back to its maker. Medalla encourages viewers to use the available thread to embroider whatever they please onto suspended fabric. Stools circle the evolving fabric so that both friends and strangers can work simultaneously on the piece. Medalla supplies both self-expression and communion.

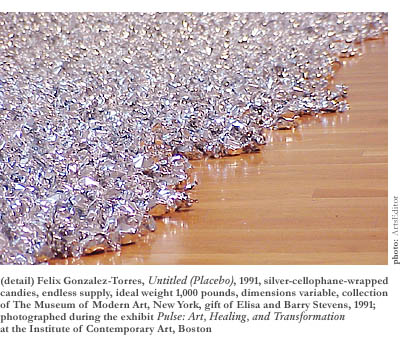

So long to “art is not for touching.” Life is clearly too short. The threat of death engenders a depth of experience. Artistic reactions to fear and entreaties to faith are profoundly captured by the curators of Pulse: Art, Healing, and Transformation. The forerunners, Beuys and Clark, have paved the way for a varied cast of artists (which also includes Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Irene and Christine Hohenbüchler, Leonilson, Wolfgang Laib, Hannah Wilke, and Richard Yarde) that continues to question art’s relationship to illness and healing, although very few follow directly in their footsteps. Certain elements of beauty in the works attract viewers to play, engage, even to eat candy off the floor while pondering the psychotherapeutic effects of placebos. Brave in its quest and rightfully lauded for that audacity, this exhibit lends many means of transcendence with all of the required gravity and grace.