When artists employ their artworks in the service of political, social, and environmental causes, critics must not confuse activism with artistic merit. Certain forms of art call attention to ills in society and may even induce public involvement, yet art is not an effective vehicle for change if the objects at hand do not carry their messages in an engaging arrangement of forms and images. Ambitious artistic statements and generous press coverage of worthy causes are no substitutes for good ideas.

The new semi-permanent exhibition currently on view at the Boston Harbor Shipyard, titled HarborArts Outdoor Gallery and featuring more than 30 artists, does bring people together toward its purpose of fostering ocean conservation, yes—though it remains to be seen whether some tangible citizen action comes out of the text of this project. But as far as aesthetics bearing the environmental message, the show is a failure. The works as a whole create no spirit of sociability through their artistic qualities. It is highly doubtful the public will take up the cause of water resources protection from the art alone, which, with a few exceptions, fails to turn the tide.

Billed as an international display, it opened on June 12th and will remain on view for six months to two years, according to Steve Israel, contributing artist and founder of HarborArts, a global community using public art and the Internet to invoke individuals, communities, and corporations to respect our water resources. The Urban Arts Institute at Massachusetts College of Art and Design facilitates public art and design projects, and is collaborating on this exhibition, as is the Massachusetts Ocean Coalition, a consortium of environmental, commercial, and recreational interests. The exhibit was juried by Randi Hopkins, Associate Curator at Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art.

Bereft of an overriding theme other than “ocean stewardship,” the exhibit welters in its own confusion. Some artworks defy logic in their inclusion, such as Donald Gerola’s Nirvana and Dr. Seuss, a whimsical stack of hats straight out of The Cat in the Hat. It has absolutely nothing to do with water protection, nor is it one of the kinetic sculptures he promotes on HarborArts’ Web site. One also questions Randi Hopkins’ inclusion of Fiddler, a giant meat cleaver in lime green. One of Robert Craig’s “skeuomorphic” works—abstract forms derived from industrial and domestic objects—the piece is intended to arouse associations with the natural world. Fiddler refers to the fiddlehead fern, as the handle top resembles. All well and good, but fiddleheads have nothing to do with water conservation.

The rift between successful public relations vis-à-vis clean waterways and solid artistry may be summed up in Carolyn Lewenberg’s Traffic Light. Using oriental bittersweet vines collected by volunteers on Boston Harbor’s Bumpkin Island, the artist claims that, “Instead of seeing this vine as a horrible problem, I’m turning it into a readily available resource for art-making.” Her heart, like the exhibit, is in the right place, yet Traffic Light comes short of signaling its red light on our proclivity for pollution. There is no urgency of feeling in it.

Most of the artworks fail on an organizational level. Every artist is linked to at least one Massachusetts Ocean Coalition member organization on the information panel accompanying his or her piece, but in most cases, the pairings are completely arbitrary. Speaking about Kelp Meal Makes Excellent Soil, a sculpture depicting kelp, artist Paul Howe contends that steel and concrete need to be respected, as they have a “life” of their own. Is such a work and statement appropriate for an exhibit inspiring us to move away from deleterious man-made processes and toward the eco-friendly? It is likewise dubious that the New Bedford Whaling Museum should sponsor a piece, as the museum honors an industry built on the depletion of creatures now endangered, despite the museum’s inclusion of cetacean conservation workshops in recent years.

And in that vein of inappropriate sea creatures, consider the centerpiece of the show—Codfish, a 40-foot steel sculpture by HarborArts team members Bill McCormick, Marc Casasanta, Roger Baker, and Steve Israel. One would expect this once symbol of Massachusetts to carry the day. It fails to do so. Platelets of steel representing scales near the upper torso gradually dissolve at the lower torso so that the back seems to be a skeleton. Fins continue this motif. It seems to prophesy the fish’s death and the death of sea life. Its political message rings true; notwithstanding, the piece is unremarkable.

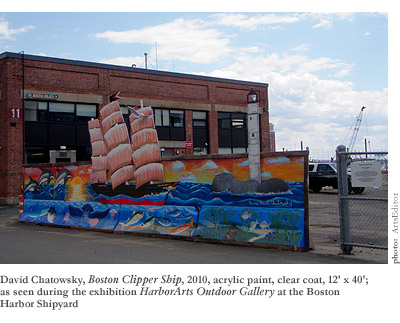

Chagrin aside, some works are so ill-conceived that they only roil up the exhibit’s waters into murkiness. David Chatowsky’s Boston Clipper Ship, kitsch of the highest magnitude, painted on the elegant background of jersey barriers and plywood, is more appropriate for a roadside Florida seafood restaurant. Two by Sea, by artists Lisa Hein and Robert Seng, is a conceptual work that is also postmodern in its pastiche of an American icon, Paul Revere’s lanterns (hence the title). A digital print on vinyl of the lanterns reveals a rippling effect akin to a flashback sequence in film noir. The artists’ statement includes the following:

A humble light burns out, but comes back with a vengeance. The Yankee lamp goes virtual after snuffing itself in soot. Yesterday’s Solitary Sentinel teams up to light the earth, or maybe scorch it.

Paul Virilio might use such prose to great effect, but this is hokum, pure and simple. Can an artist be excluded for his statement as well as his art? Both should apply here.

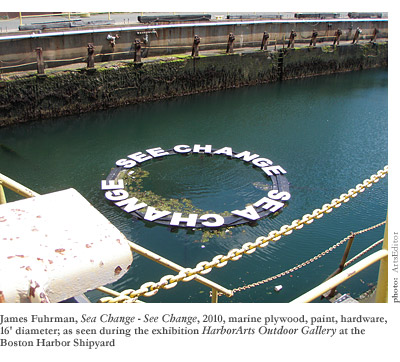

In a world so rich with environmental art since the days of Alan Sonfist, we might cogitate on the exhibition that might have been. Betsy Damon, known for her water parks, might have contributed something akin to her Keepers of the Waters project, in which Dai Guangyu took a series of photographs and allowed them to decompose in shallow dishes of polluted river water. Mark Fischer might have put forward his “wavelets,” visual readings of the sound frequencies of whale songs, to connect human to endangered sea mammal, as Codfish fails to do. Ichi Ikeda might have fabricated one of his 80-liter water boxes, part of 80 to 80,000 Liter Water Box, for World Water Ekiden. In that admirable project, the artist created Lucite boxes holding the water needs of one person in the world for a day. Some use that much. Some Kenyans get by on 5 liters. Some Americans use 1,000 liters. Instead of James Fuhrman’s conceptual fabrication Sea Change – See Change, a floating life preserver made up of plastic words being saved from “drowning,” an artist might have rigged up a water sculpture that nets in sea trash to become part of the art.

This exhibit of possibilities would do well to include the several laudable works presented in HarborArts Outdoor Gallery. Paul Sargent’s Untitled Seaway Studies documents the harm done by shipping on the Saint Lawrence River and Great Lakes. The digital prints on vinyl depict cargo ships raking through the water from the perspective of a camera slightly submerged but mostly above the water line. These are cinematic in execution, imparting a sense of danger, as if the ships will collide with the viewer momentarily. In one, the camera looks on at a ship in a shipyard as if from a shark’s point of view in a B movie. The danger is not from the shark, but from the ships. Water droplets are out of focus in the six prints. The viewer is not really imperiled; the water itself is. Thus, the thriller “movie” is actually a statement on the beleaguered environment. Bravo to Sargent for a work of meaningful social realism.

Perhaps the star of the exhibit is a humble work tucked above the security office station where the building jogs out from the facade. Mark Millstein’s Preservation Sail Forms probably fails, as do the other artworks, in bringing about meaningful resolution in the public. Nevertheless, it is a kinetic sculpture in touch with its message of sea life preservation. Millstein is one of the few artists properly linked to his conservation partner. He depicts the Atlantic sturgeon in his project, and his twin agency is Ocean River Institute, dedicated to saving endangered species.

In his piece, four pale-colored trapezoidal sails, depicting the sturgeon, pivot and flutter in the breeze. Millstein says the sail forms are influenced by wind and water. Yet the shapes also elicit the spirit of Russian Constructivism. The masts and rigging yardarms could double for the bisecting lines of a Proun (Project for Affirmation of the New) by El Lissitzky (1890-1941). In Concepts of Modern Art, the late author Nikos Stangos explained how the Constructivists rejected art for art’s sake. Art was only for social expediency and utilitarian significance. It was science and machines that would remake the world for the Revolution. Non-pictorial forms were favored. Millstein uses the abstract forms of Constructivism, but overlays these with representational depictions of fish. In so doing, he splices the machine-age utopia of the older movement with the anti-production (or limited production) world of the environmental movement. Or maybe the artist hints at a happy medium—technology tamed to allow the peaceful co-existence of mankind and ocean life.

In another work, the merit of the art itself cannot stand without the artist’s statement, always an unfortunate occurrence. French Flare Kite by Margaret Evangeline employs the neutral, repetitive, and non-expressive forms of Minimalism, yet defies the school’s logic with a humanist twist. Grid-like rivets on a segmented, mirrored steel surface are surrounded by “halos”—like rain hitting water, says Evangeline. She indicates the mirrors reflect and involve onlookers as well as the shipyard, “…linking the ephemeral experience of what is reflected in the mirror with the permanent artwork itself.” The artist circumvents the dearth of feeling of Minimalism with a lyricism that transcends the physical artwork.

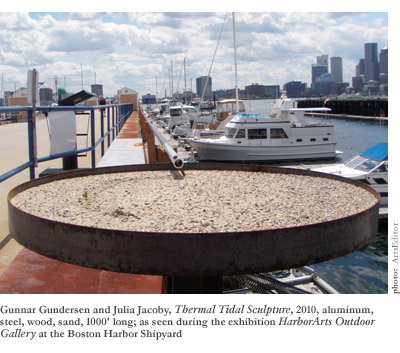

Thermal Tidal Sculpture, by Norwegians Gunnar Gundersen and Julia Jacoby, is perhaps the best coincidence between people and their cohabitation with the sea, although its message is lost to its poetry. An impressive 1,000-foot-long pole runs the length of the marina dock. This terminates in a stylus dug into sand inside a turntable, which is in turn moored by a mast, in turn tethered to the dock. The six-hour movement of the tide moves the dock, line, mast, and turntable. At last, the stylus “writes” its account of the water’s story into the sand. Suggestive of the kinetic sculptures of László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946), the installation, though flat and unassuming, does convey the ties between us and the environment. The rod embraces pier, boats, and pedestrians. The rope ties them all to the dock, and to the water in a way the other artworks in this exhibition could not. Water, people, and art are intertwined—which should have been carried out elsewhere in this forum.

While HarborArts Outdoor Gallery aims to engender a positive response from the public in the form of volunteerism, awareness, and even the commissioning of like artwork, the art by itself provides no cogent case for aquatic resource protection. The site-specificity of a working shipyard in a remote, poor (yet gentrifying) neighborhood means the public must make a deliberate choice to go see this art. That in itself is an act of consciousness-raising. But what reward awaits this determined public? HarborArts’ public relations strives to answer that question, but in an aesthetic arena, art must speak through images, not words.