There’d been a car crash out front on the sidewalk in the middle of the night, a drunk guy in a stolen car unable to make the left turn onto Boylston Street, and no one had cleaned up the debris yet. Splinters of yellow parking-light plastic. Shards of red fiberglass fender. Broken waffleworks of radiator grilling. And a big dark stain from the spilled gasoline.

It wasn’t as messy in front of the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) as it might have been, though. Someone had cleaned up after the throngs of Patriots’ Day party animals who’d crowded the sidewalk the day before to cheer the stringy Marathoners on to the finish line a few short Back Bay blocks away. No Coke cans on the staircase. No Burger King wrappers in the doorway.

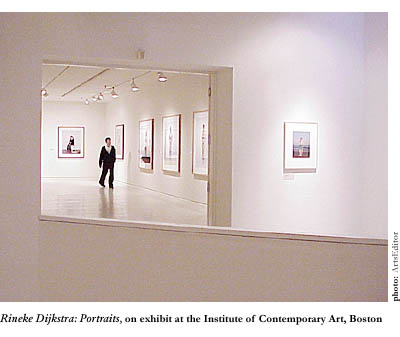

Inside the ICA, there was no evidence of either the car crash or the foot race. The temple-like museum, located in the former other half of the firehouse next door, offered sanctuary to the outcast aesthete seeking insight, solace, and a continental breakfast from a banquet table in the lobby. In a museum that used to be known for exhibiting edgy conceptual stuff that the Museum of Fine Arts proved too stodgy for, it was preview time for the press, 9:30 on a Tuesday morning. From among the chatty mix of ICA staffers and local arts writers stepped Jessica Morgan, the curator of the three exhibits on display until July 1st, looking sharp in her Star Trekkish spacewear and sounding sophisticated with her British accent.

Morgan started her brief tour of the exhibits with a captioned look at the One Hundred Models and Endless Rejects of Marlene Dumas, a gregarious white South African-born artist whose felicitous facial inkwash-and-watercolor treatments of famous women (mostly) occupy a large portion of the third floor gallery. Morgan finished the tour with an introduction, on the lower level, to the dark-skinned, close-cropped, sharp young Laylah Ali, winner of the 2000 ICA Artist Prize, and her seven scary paintings—social science fictions, if you will—of androgynous, cartoon-figure Greenheads depicted in the act of committing various atrocities.

In between, in the main gallery on the first floor, Morgan offered comments on the portrait photography of Dutch artist Rineke Dijkstra, a focused and forthright woman whose plain style and pluralist subjects owe something to her background in photojournalism.

If the impressionistic washes of Dumas and the concise illustrations of Ali both seem scoffworthy on distant first impression—the former for overbearing quantity, the latter for overbearing irony—both exhibits age well. The same is true of Dijkstra’s four sets of portrait photographs. On distant first glance, they look bland and monotonous, each subject looking the camera full in the eye and never with much conspicuous expression. The photos look at first like the gaunt and grim Eurochic complement to Cambridge photographer Elsa Dorfman’s somewhat cloying documentary Polaroids of arty Boston-area families. But closer looks at the four series of photos surface the sincere subtleties of the pictures.

First—if two photos can comprise a series—there’s the quiet, curious, before-and-after portraits of Tia, one made (according to the artist) shortly after Tia had given birth, the other after she’d recovered from the consequent exhaustion and gathered her scattered energy. There’s not a great deal of difference between the two photos, it seems at first—and then it seems there is. The attention goes back and forth comparing the shadow-bordered shapes of her face in search of a clue to the latter’s lighter spirit. A few minutes into it, the images seem to represent twin sisters rather than two conditions of the same person. But it is the same person, seen from the exact-same perspective under the same atmospheric conditions, controlled to highlight the contrasts.

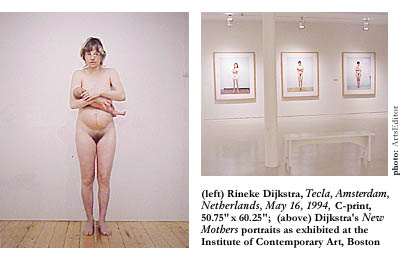

The absorbing effect of these inconspicuous studies of the sensuously plain young mother owe a lot to her bare shoulders and the blank backdrop. Likewise, the three photos in the next series are set in neutral territory. Practically life-sized treatments of nude young mothers taken (again according to the artist) in the privacy of their homes not long after delivery, they resemble one another in the sheer plainness of background. Is it a brightly tiled hallway in a stucco Amsterdam apartment building? Is that a door frame bordering the picture plane, just inside the plain frame? Is that the doorknob of a closet barely visible at the other border? An electrical socket defining the off-white wall? The light brightness of the setting brings forward the raw respective features of the women with gently persuasive force. Their bodies, warts and sweaty brows and Cesarean scars and blood-trickles and all, will not be denied and cannot be ignored. Each appears to be comfortable with the pose, holding to her breast her womb-ripened baby, as red and raw and primordial as a newly hatched bird, with a firmly determined maternal grip that pronounces the tendons in her hands and forearms. Each seems content to publicize her secrets, unconcerned that she could be losing her privacy.

The brown-haired and brown-eyed Saskia (named for Rembrandt’s wife?), with that rosy glow to her limbs, cheeks, belly, with the wispy bush, the one exposed breast—she has an intelligent peasant’s healthy appearance. She will do well. The scrawny Julie, freshest of the three from the delivery room experience, in panty-shielded hospital-issue underwear grinning with nervous, endearing, fearful glee, holds on tightly, unembarrassed about the small tattoo on the front of her left thigh. She’ll do well too. And the tough, dirty-blond, full-lipped Tecla, most shocking and elemental and courageous-looking of the three for the trickle of placental blood that has made its way all the way down her inner thigh to the knee (where it finds its groove in a calloused, elephantine knee-wrinkle and disappears down to the calf)—she’ll do fine. The photos say they will all thrive in motherhood—and that all mothers by the nature of the nurture will thrive in motherhood—and do well by their children. The Pieta indeed.

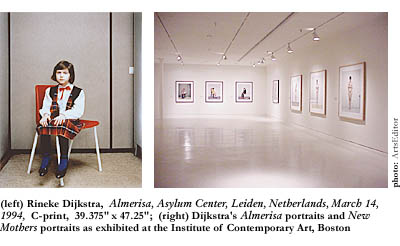

More or less neutral settings also provide free range for the subjects—or rather the subject, singular—of the four large color portraits documenting the coming-of-age of a young Bosnian refugee named Almerisa. (If these photos are lab experiments, at least the scientist is benign and humane and not in the business of creating a master race.) Again the effect is phenomenal, flushing out the figurative pheasants of character and culture from the underbrush. At ages six, eight, ten, and twelve, Almerisa takes her seat in an uncluttered, cheaply furnished interior (unlike any lushly velveted or rustically woodened atmosphere in a classic Dutch portrait) that could be the hallway between two cube-shaped bedrooms in a high-rise apartment building. At age six her feet don’t even come close to touching the carpeted floor. Sitting in a red plastic chair, she’s dressed in a plaid jumper, a clean white blouse (with a red bow at the throat), and noticeably royal blue socks—a formal-looking, composed little girl with melted-chocolate eyes and warm-toned skin that aren’t done justice by a Scottish-highland Sunday-best wardrobe. At eight, she’s in a yellow butterfly-print dress, girlishly old-fashioned clean clothing her parents must have been proud to provide, black patent-leather shoes and white socks with pink trim. As she ages, her feet get closer to the floor—they touch tip-toes by 10 and are flat on the floor at 12—and her clothes get more stylish, going from long pigtails and red fingernails and black clothes at 10 to white jeans and a bright blue jersey at 12. She starts to slouch a bit at 12, too, as if to deflect attention from the breasts she’s budding. But the composure and brown-eyed confidence is still largely there. She still looks like she has her things together at 12—the awkward refugee turned into self-reliant immigrant maybe. It’s as if she has accumulated enough energy from the previous three sittings to propel herself forward into several more sittings that Dijkstra would be welcome to show us every other year as long as she can, as the British filmmaker of the documentaries 7-, 14-, 21-, 28-, and 35-Up has done every seven years with his motley collection of citizens.

Who knows how much personal history can be inferred from the clues of clothing, posture, and facial expressions? Rineke Dijkstra knows, that’s who. The answer is not blowing in the wind but bathing in the chemical solution in the dark room.

Back in Bosnia, things were not going well while Almerisa was coming of age as a refugee in the Netherlands. Would she have conveyed a sense of well-being sitting for photographs every other year in Sarajevo? We are glad she made it out of there with her family, whoever they are. Glad she’s on her way to being a wholesome young adventurous woman with enough on her mind to keep her busy and a good heart in her healthy body that gives focus to her eyes and glow to her skin.

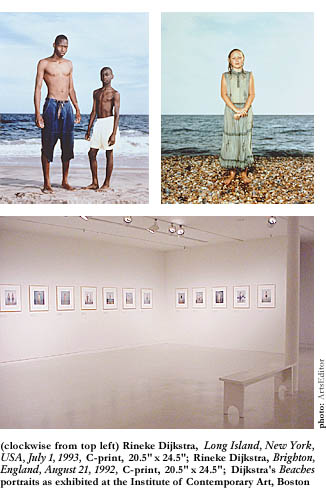

We are also glad that Dijkstra goes to the beach to take pictures, because the ones she shows us at the ICA are wonderful. At the entrance to the exhibit, the lone photo of a barechested, fairskinned eight-year-old on a beach, redheaded and freckled, is easy to walk by when a full magnetic view of the large room is pulling on the eyes. But it is impossible not to pause by this photo on the way out of the ICA to the cacophonous scene on Boylston Street at the edge of Copley Square. By that time, the 20 other color, 12ish-by-15ish photos from the Beaches series, made in the neutral controlled-experiment settings, will have been seen.

The unsterilized laboratory in which the social-scientist photographer observes her next young subjects is the bare beach, under the fathomless sky. The figure stands against and consequently defines the stratified backdrop that goes (bottom to top) from sand (or in a few cases, pebbles), to foamily crashing surf, to rippled incoming tide (relatively roused or placid, depending on the experiment’s climatically uncontrolled conditions), to sky (stormclouded or whitewisped or somewhere in between). The vertical figure intersects all four of these horizontal, Rothko-reminiscent strata, serving to link the strata to each other, to draw attention to the dynamic and quietly exciting individual combinations of color and texture, and to highlight the relation between climate and color and even (though this may be stretching it) culture and climate. Fully authentic, completely respectable and sympathetic, always between prepubescence and later adolescence, the subjects pose for the photographer consciously, plainly, and unsmilingly, without saying “Cheese!” If “style is the man,” then they are what they wear; their apparel speaks to their culture and character. There’s something inevitable about them. Fate looks fixed in their faces. The weather looks exactly the way it should.

There’s a fair, unflustered British girl, fresh from a dip in the Channel, in an apple-green dress on the beach in Brighton against a dark sky, the variegated, egg-sized pebbles she’s standing on more interesting, somehow, than the fine gray sand seen in many of the other photos. There’s a pouting, ripe-limbed, American sex-kitten-in-training on the beach at hoity-toity Hilton Head, South Carolina, in a two-piece, salmon-colored suit cut thonglike below and fringy above, the moody sky quite a bit short of calendar-girl perfection yet allusively representative of the mood in her face. There are two panther-lean African-American guys, younger and older brother maybe, facing each other at quarter-turn and looking at the camera, the younger and darker one in his bright yellow trunks full of an unchallenged confidence, the lighter and taller one milder in his knee-length cut-offs, the deep (and deep blue) sea behind them crawling to shore to stain the tan sand darker under a cloud-wispy light blue sky. There are two late or even post-adolescent Belgian young men flanking a shorter if equally tawny peer, their trim trunks and sinewy upper arms bare and pale, the dark sand and light blue sky somehow as incongruous as the pallid and browned surfaces of skin. And there, in the two-piece green suit that she has apparently been up to the waist in the ocean in, is the Botticellian Venus girl on the northern shore of Poland, her languid, upright posture (curve of hip and tilt of head) reminiscent of the iconic Italian model, even though she’s standing on the beach itself and not on a mythic, scallop-shell surfboard.

These “bathers” photos are worthwhile just for making it easier than usual to stare with real interest at details of the seascape. Beach, surf, tide, and sky—those four seascape strata, those four horizontal sections of the picture plane, are nearly identical in proportion from Dijkstra photo to Dijkstra photo, but they differ as widely in color and texture as her subjects do who foreground them and put them in focus. It reminds us how varied and bountiful nature is, really, and also how rarely interrupted is the view of the sea from the shore. Oh, gulls wheel around all right, squawking and looking for rotten fish. Cormorants skim by, parallel to the shore, on their way back to hell, where Milton said they came from. Extremely territorial terns dive for fish when they’re hungry and for humans when they’re angry. Ducks bob on the surface in peace-loving platoons, and sandpipers scurry across the gleaming sheet of water you can see your own beachbum image in. Maybe a sailboat or a tanker drifts like a toy across the horizon. But these are small, quiet events, even when accompanied by cries, quacks, or horns. The beach, of Long Island or Belgium or England or anywhere, is a nice place to get away from all of the cacophony. It’s kind of like a sanctuary. It’s kind of like the ICA.