The conclusion of the Cultural Revolution and the death of Chairman Mao Zedong in the late 1970s gave birth to a new generation of Chinese artists. With shackles off and the doors to the West reopened, the artists of the ’80s embraced Western culture, especially modern art. And so began the renewed projects of a self-focused modernity initiated some sixty years earlier—Chinese artists, for example, being among the first to articulate the impact of huge transnational corporations in the transformation of their society. China was making and remaking itself so quickly that the loudly lauded exhibit of contemporary Chinese works held last year at Ethan Cohen Fine Arts in New York had its title changed from Made in China to Making China, because the former did not do justice to the speed and vitality of a country bent on remodeling.

Inevitably, from the frenzy to identify themselves came the artists’ desire to position their work in the newly available international arena. The blossoming avant-garde that had focused on local politics and questions of cultural identity in many cases abruptly shifted to a neo-avant-garde favoring international involvement. Artists at one time ambivalent about the Cultural Revolution’s role in their creative process found that their work was far more salable when glorifying the persuasive power of Mao’s propagandist art. Political and cultural distinctions had become fodder for a buzz the likes of which once surrounded Soviet art.

Chinese artists living abroad have the responsibility of producing work from a space “in-between” the East and the West—a Zwischenraum—struggling to present original content and milieu insofar as is possible in the very different context of the Western museum. This “transexperience”—to borrow the term coined by artist Chen Zhen, whose posthumous exhibit at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston late last year dealt, amongst other themes, with the experiences in viewing one culture through the lens of another—is yet the center of more debate. Ideas of transexperience are considered either creative catalysts or overly characterized by Western tastes. Many overseas Chinese artists are accused of basing their work on outdated and rarified stereotypes, and are considered no longer part of an evolving, dynamic culture. Yet artists like the much feted Cai Guo-Qiang (known by most for his incredible fireworks displays) find the discomfort of exile mitigated by the advantage of an external perspective. Nevertheless, there is evident risk of artwork produced both on the mainland and abroad collapsing into irrelevant traditionalism or a displaced mimicry of Western precedents.

That said, a visit to a Chinese art gallery in Boston sounds like the recipe for an anxiety attack, despite the fact that this gallery is well-known in the area for its calming tea. I can reassure you that the experience is, dare I say, a relief?

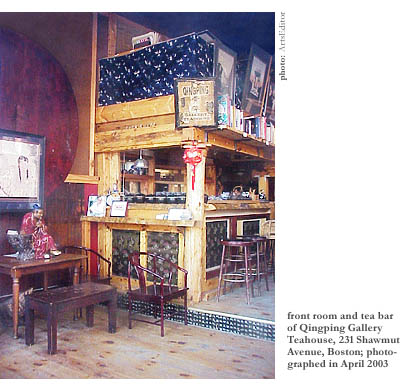

So Long, Not So Long Ago, the current exhibit (through May 31st) at the Qingping Gallery Teahouse, is the most recent result of owner Wu Jianxin’s unique, European salon-style alliance with artists living and working in China. The gallery, located at 231 Shawmut Avenue in Boston’s South End, rotates exhibitions of contemporary Chinese art with the aim of giving its patrons a new understanding of modern Chinese culture. The venue also manages to lend a few new perspectives on the presentation of works of art. And, for that matter, the serving of tea. This “Renaissance man” of establishments also hosts musical escapades of the acoustic, electronic, and avant-garde variety. Qingping is open seven days a week from early afternoon to midnight.

In a fashion entirely opposite the all-too-familiar stark and minimal gallery setting, the Qingping Gallery Teahouse is immediately both confusing and stunning at the moment of entrée. Even the tea menu is slightly daunting. The small tea bar leads into an inviting back room with couches, slate tables, and antique horn-back chairs. I’m not sure if it’s feng shui or the strength of the pu-er tea that enables your initial agenda to lose itself to the fish tank, the book collection, and the apparent Zen of bathroom design. The lofty second floor, on the other hand, makes you feel a bit like you’re not supposed to be up there, which, I might add, is the fun of it. The dimness will require you to turn on small lamps as you go. Subtly, a soft yellow light hits a fiery red and black lithograph and you’re reminded—of course, the art! The gallery strikes a happy medium between readily available, tangible works on display and the joys of discovery.

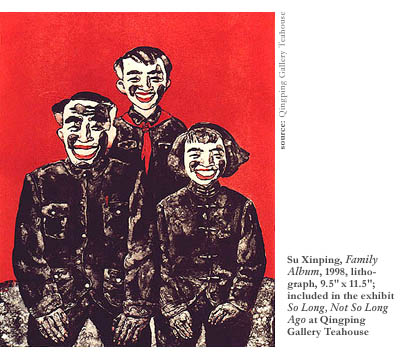

The second floor lithographs are all by artist Su Xinping, serving as a miniature retrospective. (If you have the clairvoyant suspicion that your double-parked car is about to be towed, certainly spend all your remaining time right here.) Xinping is undoubtedly the most internationally renowned artist in the exhibit and one of the most prominent Chinese artists in the international scene. Ironically, his work is so removed from both official and avant-garde trends that the entire crux of the Chinese contemporary art problem effortlessly dissolves. Xinping instead creates works marked with a reserved introspection. The superbly executed lithographs highlight more traditional content and media, finding inspiration in ink and wash techniques. In the three 1995 works from his series Sea of Desire, Xinping alludes to the pressures placed on people in a climate of rapid economic development, drawing especially on the hectic emotions involved in such exceptional circumstances. Black and white figures, deep in their simplicity, sprint across the paper amongst a crowd of waving hands not unlike the edge of a stage at a rock concert. Sea of Desires, III portrays a man taking a swan dive into a sea of anonymous hands, a leap of total self-abandon.

Xinping’s most recent works in the exhibit, spanning from 1998 to 2000, reflect his recent ambitions to concentrate on his technique and to replace the original focus on loneliness and spirituality in earlier works with satire and humor and even the occasional optimism of color. So while Zoupin IV shows a man partially obscured by his own background, Family Album, completed in 1998, changes the attire of the characters from traditional Mongolian robes (predominant in his early work) to the androgynous suits worn by China’s past officials—the so called “Mao Suits.” The figures are smiling with bright red lips against an equally red background. Su Xinping is able to find humor in the past.

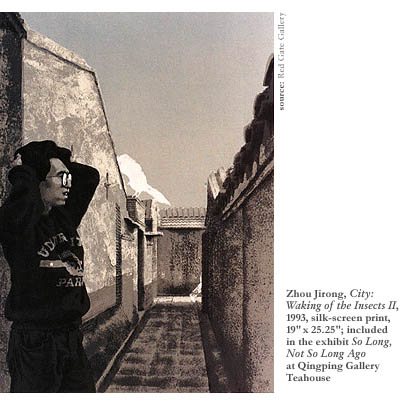

Suspended from the upstairs railing are three works by Zhou Jirong, two being the last of a series and all being the last of a style for him. While I’ve been told his latest undertakings have been very abstract works in extremely large proportions, the three silk-screen prints in this exhibit clearly and skillfully reflect the transformations of cities during China’s drastic period of modernization. Never-ending destruction and construction take their toll. The conditions in modern China of late have imparted a sense of absence and loss in the urban environment, which Jirong transposes in his works of extreme sophistication. The skies are serene against the rough edges of hutongs (ancient city alleys), in their deracination.

Time Space Memory V suspends a hutong in space, with muted colors battling for the edges of the architecture. There is a sense that the object is about to be slowly pulled away from the viewer, into the distance. The urban experience is a hazy one, and in City: Waking of the Insects II, a man stands amid the loneliest of labyrinthine walls. The point of focus is somewhere beyond what structures remain. Everything looks as if under moonlight yet it isn’t. Perhaps it is daybreak. The man looks as if he has just finished his daily run. His slight expression of exasperation, however, could be from a multitude of sources. The strange natural light is as much a dreamlike quality as it is a sentiment of total displacement. It is interesting to hear that Jirong’s new work is turning to complete abstraction and making strides away from this realistic solemnity. His larger works will eventually be on display in Wu Jianxin’s recently purchased warehouse space in the burgeoning gallery district of Chelsea, New York.

The title of the exhibit, So Long, Not So Long Ago, refers to the rapid movement and change in Chinese society and the art that seeks to define it. The exhibit itself signals the return to something more traditional and bids so-long to the Pop Art that has dominated output since the ’90s. On my way back through the tea bar en route to the other pieces in the exhibit that I originally bypassed, I asked Jianxin what the unifying factor was in choosing these particular artworks. I had yet to ask him about the exhibit’s conceptual ambitions. “There is none,” he responded, looking up from his laptop computer. “I didn’t come up with a story.” He grins.

The ceramics by Christopher Howe (Lee Mignan) are perched at waist height in a relatively dark space and manage, at first sight, to feel incongruous—even in an exhibit with no apparent plot. There is a particularity in the way in which they are made—each ceramic is vaguely like the next, all based on a flat, square shape. Shapes are convex and concave; some trickle down the sides. I will admit that on my first visit to the exhibit I was not at all engaged by Howe’s work. Yet on my second visit, I managed to find stacks of his ink paintings, unmarked and untitled, leaning against the wall upstairs. I was stunned both that I had missed them and at how perfectly they were wrought. Thick, loose black strokes surround amorphous, pastel shapes. Abstract Expressionism, slightly subdued, is combined with ink strokes and lines that mature the work far beyond the ceramics the artist created two years prior. Howe is definitely on to something. I went back to look again and again, making trips up and down the stairs to find vestiges of his early ceramic work in the paintings. They are so humble in their approach that they remained untagged, each piece hiding the other, practically tucked away. Howe has spent the majority of his life in America and has actually pursued the reverse commute, traveling to Beijing to further his study in ceramics.

Similar by virtue of striking diversity in a body of work are the ink paintings by the “new-comer” Jordin Chi-Yan Chau. Chau feels that growing up in Hong Kong, a then British colony, denied her a certain appreciation of Asian art. Studying in Beijing eventually led to an embrace of the flat and sparse images that were bereft of the excitement of Western art. Pensive and slight, in a slightly naive series cigarettes are chosen as subject matter to create minimal compositions in the style of lithe rice paper paintings. Chau’s series is mounted on traditional vertical scrolls and hang on the walls and windows of Qingping’s back room. Enjoy Loneliness is the portrait of a single cigarette lit and floating in space, emitting a careful thread of smoke. Others use multiple cigarettes to allow tangles of smoke to drift up the vertical rice paper.

A single work by the hand of Liu Qinghe hangs near the entrance: Hope. Qinghe uses the traditional medium of ink and color on paper. His figures tend to be anything but traditional, however, and generally possess a grotesque realism. Exaggerated facial expressions manage to reveal very little emotion. The woman in Hope likewise invokes a remoteness alienating to the viewer. The banality of her very existence on the paper encouraged me to look for more. Her gaze is set somewhere between the viewer and nowhere at all. Qinghe’s “characters” are almost always a commentary on the superficiality of the middle class, the way the painful boredom of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s characters commented on the German upper class of the late 18th Century. Her body, lying on its stomach on a bed stretching towards the viewer, manages to be neither two- nor three-dimensional. Her presence toys with flatness and foreshortening. Her skin is pale blue if at all, her presence flickers within her own silhouette, and the sheets of the bed are so thin we can see through them. The effect is simultaneously eerie and calming.

Also hovering near the entrance are the most diminutive works of the current exhibit, consisting of five paper-cut and Chinese ink works on rice paper by artist Song Xin. The medium reflects the Kiragami folk tradition of paper cutting and folding. From her series Dream and Life, Xin’s dreams are her primary source material, manifesting in auspicious imagery that draws on the parallel worlds of the unconscious and conscious in order to come into being. For ancient peoples, dreams revealed prophetic signs and had diagnostic significance. Indo-Tibetan Buddhism dreams were regarded as an accepted form of cognition and as portals to powerful states of consciousness. Biographical Thangkas—religious paintings—gave dreams a narrative and pictorial form, not unlike the effect Song Xin achieves.

In hindsight, none of these works of art is inextricably bound to the others or to the exhibit itself. So Long, Not So Long Ago therefore manages to fall on either side of the multitude of controversies surrounding the subject. While contemporary Asian arts and the concomitant understanding of them are burgeoning in the UK, Europe, and the US, they are unfortunately still a sideshow, and exhibitions like this one are in great need. Wu Jianxin has generously eliminated himself as an author, giving pride of place to the receivers. Qingping Gallery Teahouse offers an experimental and experiential, rather than didactic, approach to presenting works of this genre.