The word “memory” comes from the Indo-European root meaning “to mourn”, and in Greek myth, Memory was the mother of the Muses. The Materiality of Mourning, an exhibition by Colombian sculptor Doris Salcedo at the Harvard Art Museums through April 9, 2017, unites these sources of inspiration. Her sculptures, assemblages of furniture and newer works, in modes of fabric, are functional memorials for anonymous victims of political terror and injustice. Using a limited palette of forms, but devoting a wealth of time and concentration, she has earned an international reputation with her powerful, sobering, and cerebral sculptures.

Artists, enmeshed like Salcedo without chance of escape in a decades-old culture of political violence, must distill forms that express the despair and loss forced upon them. Art created to skirt the horrors their country enacts, and the artists who ignore them, are lost to the ethics of art history. Witness the state-directed Social Realism of Stalinist Russia, or the kitsch of fascist regimes. The art critic may also be obliged to comment about his own country now similarly sliding into hatred, divisiveness, and the stockpiling of arms. Historical analogies abound, acknowledged and not.

Compare and contrast not artworks, but nations. Colombia, and Columbia, as patriotic poets call the United States, are named for the navigator who exposed the treasures of the western Atlantic to Europe’s metal-crazed rapacity. Like the United States, Colombia is a multiracial nation fronting two oceans, with three mountain ranges, and valuable mineral resources that support its economies, licit and illicit. Revenue is derived from cultivating stimulating substances: coffee, coca, and cannabis. Recall that the United States’ agricultural economy depended for centuries on exporting tobacco. High value commodities, especially addictive ones, lead inexorably to organized crime in under-regulated territories. The United States still has a powerful federal government that enforces laws in outlying districts. In Colombia, the government is less powerful and cannot control all parts of the countryside, where illegal gains from cocaine or emeralds are laundered into legitimate plantations.

Guerrilla forces arose to protect the people against the landowners and the government, but at the price of vicious brutalization. The government responded by arming local right-wing militias. Thus Colombians were at risk from a spectrum of armed political groups. During La Violencia, which lasted from 1948 to 1958, people met the most hideous ends in tens of thousands of torture murders. Civil war continued informally until last autumn, when Congress ratified a peace with the FARC that was narrowly defeated in a plebiscite in October. Colombia may or may not remain divided.

A somber, funereal aura of dread hovers around the four dimly lit galleries that house Salcedo’s Harvard exhibition, with its threatening, altered objects. Something has happened, something evil. These brooding creations and strange vestiges are a coded relation of events, indecipherable hints of a painful process of negation. Salcedo’s assemblages of furniture are essentially monochromatic, and their effect is of immense heaviness, both in their physical mass and in their implied burden of despair. The means are spare, and the surfaces are as if stripped away, a metaphor for loss of liberty and human connections.

Two similar artworks, each identified as Untitled 2008, consist of conjoined bookcases, armoires, and chests joined at one end to a table. The long tables—farm or cottage industry style, maybe from a kitchen, where a dozen agricultural workers might process food and eat together—are grafted onto the toppled containers. Each sculpture is about one pace by two paces, and stands about hip height. Made of solid wood, they were until recently antiques, with patterns of wear and stresses that families might have impressed over generations; domestic containers for the clothes that identify their place in society, the bookcases that held intellectual content: the worldly elements of life lived in houses that should protect them from a culture of political risk. Mary Schneider Enriquez, the exhibition’s curator, wrote the insightful catalogue essay, and she compares them to the heaps of hair and belongings shorn from Holocaust victims, whose preservation proves the existence of the vanished.

The traditional joinery of the furniture is complemented by Salcedo’s precise woodworking. Her splices extend the entire lengths, widths, and depths of the constituent units, attached in parallel, at right angles, or skewed. Then they are up- or side-ended, smacked uselessly against one another or the floor. Reassembly has undone their purposes, and to preserve their inutility forever, nine tons of solid gray concrete fill them to their brims. Concrete is not typically used for monuments, but for burial vaults. Neither tombstones nor cenotaphs, they are remains.

The pared-down concept Thou-less and two untitled works is one ordinary household wooden chair cast in stainless steel. They address the loss of a person grammatically close by reason of love or family. The chairs might be single, arrayed in small groups, or wedged together into impossible compoundings. Each has four legs and a seat. All of them have been mutilated, beheaded: their backrests removed, the two stiles point upward without purpose.

Most of the solid steel seats and aprons are in standard dimensions of milled wood, but some have been cast thin, about the thickness of cardboard. This enables Salcedo to further wreak information into the work: eroding or burning as with a cutting torch or acid; wrenching apart across the grain. They are crumpled laterally, as though enormous compression has been exerted, the wood giving up its hardness for a moment then forever distorted. Crumpling, tearing apart, and burning are sculptural expressions of the enormity of the physical forces that destroy people.

The chairs stand for the missing people who sat in them. Their appearance and mass are deceptive. Each might weigh as much as a heavy man or woman. The obdurate surfaces have been personalized, painstakingly engraved to imitate wood graining and incidental nicks. But the grain is not consistently realistic. It may echo the human hair that Salcedo has applied in other works not in this exhibit. The inch-long grooves in one are a graphic equivalent of the needles in her Disremembered IV artwork. That in English we call these surfaces “graved” is a fortuitous linguistic coincidence.

The tops of the stiles are machine-polished for about the length of a hand before the graining starts its parallel tracks to the seat and floor. The smooth finish is of a piece with the removal of the backrests, implying the grinding away of personhood. We wish, instead, that this reduction to the smooth purity of the upward-tapering forms and the tough, untarnished essentiality of the material would demonstrate the transcendence of the human spirit over pain and assault. When the most powerful nation on earth abandons its ideals, individual acts of decency are all we can hope for.

Doris Salcedo’s newer works use fabric and clothing to reference the absented person. Disremembered IV is her response to her heartbreaking interviews with mothers of children who died from gunshots in Chicago, a present-day Massacre of the Innocents. The title is a neologism, from the inner city revival of the verb “disrespect”. To disremember—that is our universal inability to memorialize the pointless, unjustifiable deaths of children. The United States’ gun industry lobby and the right wing promote widespread personal armament; the new administration promises to ease restrictions. We are ignorant of or numb to how young children stumble daily upon household handguns and shoot, “as seen on TV.”

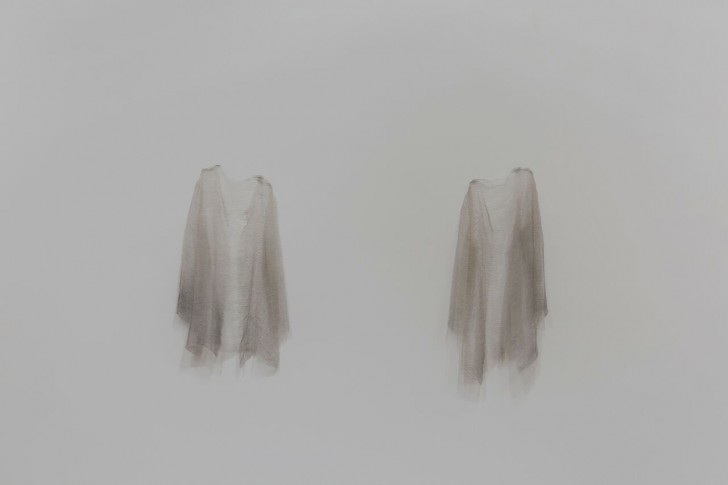

Untitled and Thou-less speak with mass. The sculptures of Disremembered IV are part shadow, part shimmer, hanging with barely perceptible support against the walls. Silk threads hand-woven into sheer mesh are stitched into simple long-sleeved blouses without closure, after a pattern that Salcedo once wore. Each blouse is penetrated with 10,000 to 12,000 slender, double-ended, nickel-plated steel beading needles inserted in and out along the horizontal threads set in vertical rows, a malignant sheen that accentuates the planes of the drape of the fabric. They appear evanescent, but are crafted from permanent materials that will last for centuries and can only be dismantled one needle or thread at a time. Like steel, silk is strong, and a luxury, highly permanent. Unlike wool, moth larvae won’t eat it, maybe because silk is moth. The metal is high tech, the needles as thin as the threads, viciously pointed at both ends. They are metal devices meant to pierce, like bullets, like the ancient spear heads or lead shot for slings exhibited nearby. You might bleed after a day of pinning these works into being.

Disremembered IV are blouses such as mothers wear, transformed into garments of suffering. They suggest coats of mail. But is there really any possible protection from random bullets? Should cities provide a Kevlar vest for every child born? Hermits wore shirts of rough hair to mortify their flesh and achieve devotion. Shirts in myth are often associated with death—for example, the tunic dipped in the poisoned blood of the centaur Nessus, which burned Hercules to death. In the Grimm brothers’ The Six Swans (and in Andersen’s The Wild Swans), a young queen must neither speak nor laugh for six years, instead weave asters (or stinging nettles) into six shirts to disenchant her brothers, magically disappeared by a stepmother. The sharp fibers jab her fingers; her husband’s court supposes her a mute idiot. The king’s mother abducts his three children, and frames their mother, the same means by which totalitarians seize power.

These blouses are like spider webs that trap human prey in unending grief. Their delicacy makes them dangerously untouchable; their apparent fragility makes them ghost-like as they hover, hauntingly. The needles amount to interrupted histories, each a day of a short life, inserted into the warp and woof of birthing, daily nursing, dressing, feeding, schooling, and life’s terminal rending by explosive and metal.

While floral content is possibly implicated in Disremembered IV, it is overt in A Flor de Piel, which memorializes a kidnapped, tortured nurse. The title is untranslatable, an idiom meaning that one’s feelings are exposed for anyone to see, like a blush, or “to wear your heart on your sleeve.”

Great storms conclude with the leaves of forests stripped from their branches, flooded downstream into mats of plant matter under swamps and seas, compressed into fossils over eons. Wars do the same with bones. In A Flor de Piel, thirty thousand individual rose petals have been laboriously stitched into a mauve and russet fabric that lies on the gallery floor, a shroud arranged with ripples that suggest the crushed form of a vanished woman. Her absence implies an event like storms of weather or politics. Petals are evanescent, yet these have become sculpture, semi-permanent, as other plants become coal. They are flattened, a geological stratum, barely overlapping each other, mysteriously preserved so that they gain strength and resistance, cohering because of the wounding stitches that join them. Wounds stitched in living creatures will heal. Stitches piercing petals are violence. This delicate work is protected by institutions of society: maintained by its museums, including Harvard’s, which owns this work. Guards let you crouch down to look closely, but you must remove objects from your shirt pockets, lest they fall and injure it.

A Flor de Piel has an extra-visual component: a faint honeyed floral scent. Roses make us wistful: their scent acts directly through the olfactory lobe on emotion; their color is that of intimate tissue—the soft, veined petals are like skin; and their evanescence, as suddenly they drop, baring the flower’s sex organs, is both regenerative and fatal. The surface of A Flor de Piel is iridescent, a faint, muted haze. You see the veins of each large petal. Roses, Schneider Enriquez writes, are an important Colombian export, and she writes that these are blood red. But they also range from dulled pinkish browns to deep maroon, like shallots, which, sliced, engender tears. The patterning and muted colors recall floral-stenciled commercial pottery of the 1950s. The vast spread of petals behaves like a population. Where the raised folds of drapery catch the dim light, you begin to see sad dark eyes, as if painted in oils. Our eyes naturally search for faces, as babies stare at certain arrangements of circles in a circle. But are these eyes or bruises?

This saddening exhibition makes it hard not to remember that around the world, terrible times lie ahead. Natural resources are running out, warming climates will bring storms and starvation, and agents of economic inequality demand that the multitudes be prevented by force from improving their existence. Art is always about awareness of better times. Condemned by their nature to make art, artists continually add to their range of means. Authoritarians are limited in their methods of making change, that is, to revert to the status quo ante. How does a violent state enforce its will? If your only tool is a truncheon, everything looks like a head.