“Amazing” “It looks so real!” “Now, this is art I can appreciate”—these are some stereotypical (and sometimes cringe-worthy) responses from both art novices and connoisseurs alike when confronted with photorealist paintings, although the latter may admit this only to themselves for fear of appearing conventional. Admittedly, I also had similar, one-dimensional responses to photorealism before arriving at The Rose Art Museum of Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts, for the opening of Double Take: Photorealism from the 1960s and ’70s, on view through July 31st. Although fascinated by the display of technical virtuoso, I never gave the genre much consideration. However, I was intrigued by the exhibition’s invitation to give these academically-neglected works another look. Curator Stéphanie Molinard attempts to situate photorealism within the contemporary art scene of the 1960s and 1970s—meaning that this movement (if one can consider it a movement) has its roots in Pop Art’s legitimization of commercial and everyday objects as high-art subject matter, and ultimately has more in common with the dispassionate approach taken by minimal and conceptual artists than more mainstream artists who feed off of the public’s undying desire for nostalgia. It’s an appealing premise, and one that aims to provide a fresh face to a seemingly predictable genre.

Photorealism delineates a type of painting and printmaking that developed during the mid-1960s where artists used photographs as the subject of their work, rather than nature. The artists typically associated with this label did not constitute a cohesive group (usually the case with retroactively assigned art historical categories), which explains both the wide range of technical methods and equally broad array of artistic intentions within the group. However, they are linked together by their meticulous, often detached depiction of photographs. The easily recognizable subject matter may have contributed to the genre’s popularity, but photorealism has often been met with harsh criticism elsewhere—perhaps, ironically enough, because of its overexposure and easy accessibility. In fact, the most common criticism focuses on the lack of profundity involved with transferring a photographic image onto canvas. “All that remains is the technique: that elaborate, deadpan verismo which has propelled Photo-Realism into its popularity among those collectors who, wearied or intimidated by the ideological conflicts of the sixties, have no appetite left for ‘difficult’ art.” Written by art critic Robert Hughes in 1974, it represents the type of opinion that the current exhibition intends to dissipate.

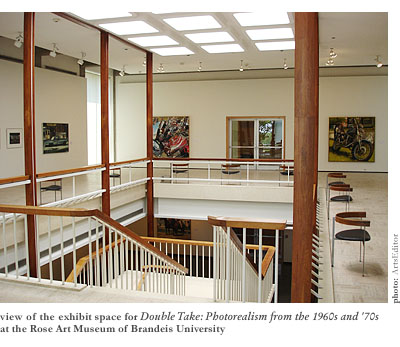

In an attempt to counter claims that photorealism offers nothing more than painterly aptitude, the wall text and exhibition catalogue challenge the viewer to look at these works in terms of art historical significance—meaning their relationship to dominant art trends before and during their time. Additionally, the exhibition design significantly contributes to the overall purpose of recontextualizing the genre. It is composed of fifteen large-scale paintings and nineteen prints—the majority being part of the museum’s permanent collection. Running concurrently with the exhibition is an installation in the Lois Foster Wing by the contemporary French artist Xavier Veilhan, entitled The Photorealist Project. More than a surface-level pairing, the installation and exhibition play off one another, with Veilhan’s piece—besides being successful on its own—significantly contributing to the literal and figurative “double take” of the accompanying exhibit.

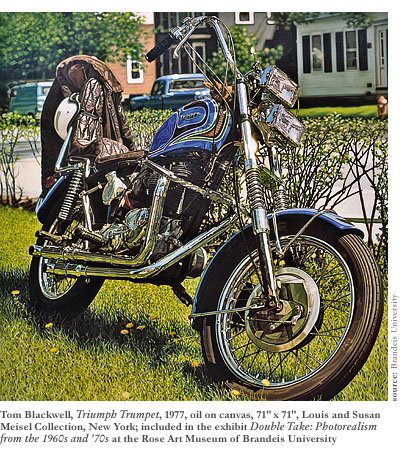

However, before leaping too far into the curatorial purpose of Double Take, it is necessary to back up and convey the exhibition as it is experienced, for it succeeds on multiple levels and is skillfully designed to be encountered in waves. Upon entering the upstairs gallery, the viewer is confronted with a visual treat—eight large-scale painted canvases frame the space and radiate with luminosity and brilliance. From across the room on the left, David Parrish’s up-close examination of a reflective bike windshield and side-mirrors in Yamaha, 1978, sparkles with bright reds and metallic grays, and dazzles the eye with reflections of reflections. On the right, Triumph Trumpet, 1977, Tom Blackwell’s meticulously depicted motorcycle parked on a sun-drenched suburban front lawn, is a vision of clarity and exactness. The paintings’ luminosity resembles the shiny new cars and motorcycles many of them represent—displayed on bright, white walls to increase potential consumers’ hunger for the new. Even after reading the wall text, it’s easy to ignore the more intellectual facet that may or may not be a part of the paintings, and simply be drawn in by the surface beauty.

On closer inspection of the canvases, however, the illusionary realness, and some of the crispness, falls apart. For example, the out-of-focus background of such paintings as Ben Schonzeit’s Cabbages, 1973, looks contrived. His source was a staged photograph with an unrealistically short depth of field, and everything outside the small point of focus is blurred. In fact, a closer look at each painting reveals that they all have a fuzzy—at times even painterly—quality. It’s clear that the artists are experimenting with illusion and perception. Step away and the illusion is on, come closer and you realize the artist is not playing games. They’re not passing these paintings off as photographs; in fact, they’re letting the viewer in on the secret of their source—representing reality through a photographic filter. Very quickly it seems possible that these artists are, in fact, dealing with concerns other than flaunting their technical skill. For instance, it’s likely that photorealism comments on the nature of our perception in a contemporary, media-infused world. Writing in 1976, theorist Jean Baudrillard, in “The Hyper-realism of Simulation,” made the hypothesis that reality itself (as opposed to symbols for it) had all but disappeared in our world. Photorealism may be an ironic comment on this very fact, creating meticulous, time-consuming reproductions of reproductions.

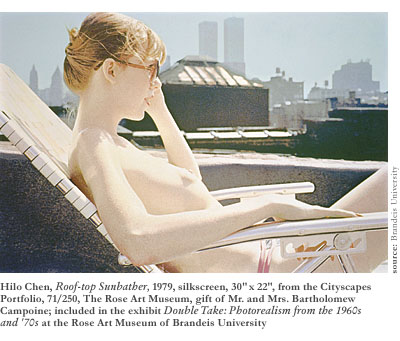

Walking downstairs into the lower-level gallery reveals more radiant paintings and prints depicting consumer-friendly objects, such as cars, shop signs, and toys. When the occasional people are depicted, such as in Richard McLean’s Diamond Tinker and Jet Chex, 1977, displaying two women on horses, or Ralph Goings’ Bank of America, 1971, depicting three customers walking in and out of the facility, they appear static and have the same plastic sheen as the toys and cars around them. It is apparent that there is no emotional link to these people—no investigation of individuality or personality. They are simply depicted as objects in a photograph, like everything else.

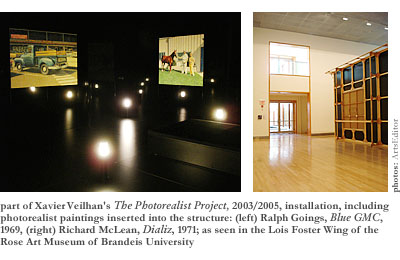

Just beyond the downstairs gallery is the Lois Foster Wing, where Xavier Veilhan’s installation is situated. Although exiting Double Take, Veilhan’s The Photorealist Project (curated by Raphaela Platow) once again puts you in proximity with photorealist paintings, albeit in a drastically different setting. Not only does Veilhan use actual paintings by five photorealist masters (Robert Bechtle, Robert Cottingham, Richard Estes, Ralph Goings, and Richard McLean) in his installation, making the connection to Double Take blatant, he also addresses some of the same issues that are brought up by the masters, including those related to perception and reality.

The Photorealist Project is essentially a gallery within a gallery. Entering the high-ceilinged Lois Foster Wing unveils a large, freestanding enclosure filling much of the space. From outside of the enclosure, a wooden, grid-like structure is sealed with black, vinyl panels. However, the grid pattern is disrupted in five areas where the paintings are inserted—instead of the black vinyl, the backs of the canvases are visible, artists’ signatures and all.

Inside the structure is a different world. The space is dark and maze-like, making it difficult to negotiate upon first entering. The only lighting comes from tubular lamps sticking up from the floor, which creates a confusing and blinding experience. Situated on the walls, above each floor light, are the photorealist paintings, looking more like slide projections than paintings. Indeed, the illusion is so strong that the backs of the canvases seen before entering the structure provide the essential clue to the reality of the images. In this way, Veilhan mimics what the photorealist painters were doing—he gives the viewer an illusion, but doesn’t try to deceive. In fact, he offers the viewer all the tricks up front; the canvas backs are the first things seen before walking into the structure.

Interestingly, by making the paintings within the structure appear as projections, The Photorealist Project brings the viewer back to the photographic source of the paintings. It’s a little like seeing the paintings in reproduction, although with more clarity. The low lighting and semi-reflective, black walls erase the brushstrokes and it’s easy to forget you are really looking at paintings. Because of this, the subject matter of the works is emphasized—Richard Estes’ crisp, clean vision of Manhattan, Robert Bechtle’s removed, distant observation of a woman staring off into space at a sun-soaked patio table. The subject matter is suddenly the focus, rather than a preoccupation with finding a flaw in the technical expertise.

Walking back through Double Take by way of the main galleries and having had time to contemplate Molinard’s curatorial premise, new insights into the genre are discovered. First of all, the subject matter of these paintings is absurd. Many of the artists used complicated photos of reflective surfaces, perhaps to emphasize their technical ability, but most of them had commercial or banal subject matter, appearing more like portraits than still-lifes. Motorcycles, cars, and gumball machines all act as primary subjects, depicted in a distant, but detailed and painstaking process. The knowledge of the time-consuming painting process is what ultimately lends to the absurdity, especially given the fact that a camera could, and did, capture the scene with one click of its shutter. Although there seems to be some sentiment inherent in spending an excessive amount of time representing an object, there appears to be little to no actual emotion expressed in the paintings. They were painted as mechanically and detached as possible, perhaps a comment on the futility of expression itself. The result is at once humorous and disheartening.

The other thing to be contemplated upon second look is photorealism’s relationship to other movements of its time, most notably Pop Art, Minimalism, and Conceptual Art. The influence of Pop Art, of course, can be seen in the choice of subject matter. Pop Art made it acceptable for serious artists to delve into recognizable images again. No longer was it necessary to attempt to convey the soul of the artist through abstract, expressionistic markings. Minimalism, too, questioned the ability of painting to express any emotions at all. By the 1960s, Americans had come to love the passionate, painterly outpourings of the abstract expressionists, as well as their outward personas, which embodied the myth of the genius/artist—individualistic, fiery, and tortured. Therefore, when deadpan, minimalist painters such as Frank Stella and Robert Irwin came on the scene, the public was shocked by their lack of expression and coldness. Their method was to strip down painting to the barest details and remove the artist’s touch as much as possible.

Although photorealist images never elicited the same public outrage as other movements, they can, in fact, be thought of in the same vein. Isn’t it true that these works are deadpan and painted with a minimal amount of expression? And can’t they also be thought of as complicated comments on the nature of perception and contemporary, media-dominated reality? However, photorealism does all this while maintaining an appearance of high accessibility and sustaining the mainstream public’s fascination with realistic subject matter. Sounds intriguing, doesn’t it? In the end, even if you don’t come away convinced of photorealism’s radical nature, the visual delight of the paintings and prints that make up Double Take is well worth another look.