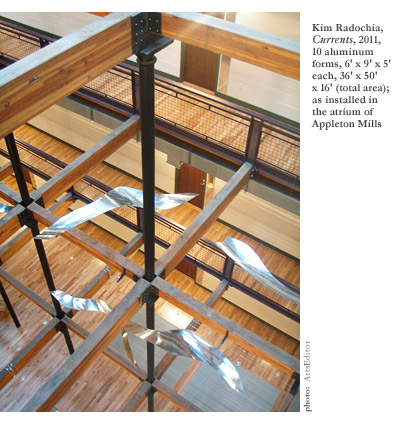

Inside the atrium of Appleton Mills, remnants of heavy industry abound. Black columns hold up hefty wooden beams. Exposed steel ductwork lines the ceilings. Metal railings criss-cross in a geometric pattern. It is easy to miss the curling forms of the atrium’s central artwork. Currents, by Kim Radochia, looks like mere wisps of reflected light. Hanging at varying heights, the polished aluminum shapes appear to float away. In the afternoon light, the piece looks like water in old black and white photographs of the surrounding city canals—locked in time but winding through the history of the man-made from past to present.

Near the gateway to Lowell, Massachusetts—a city known as the “birthplace of the American industrial revolution”—the structure of Appleton Mills sat vacant for years. It loomed gloomily over the city and reinforced Lowell’s label of a depressed, decaying mill town. Even State Senator Eileen Donoghue called it a blight, an eyesore. It was hard to imagine that at one time the mill was full of frenetic energy— mostly young unmarried women from farm families of northern New England working the power looms, transforming raw cotton to finished cloth.

A new type of transformation, though, has been underway for the past few years. As part of the Hamilton Canal District redevelopment plan, the City of Lowell, the local office of the National Park Service, and the Deval Patrick Administration, which designated the area as a priority Growth District Initiative (GDI), have restored Appleton Mills as an affordable artist living and working space. The Appleton Mills Artist Selection Board has awarded space through a lottery and interview process. The Boston-based real estate developer, Trinity Financial, designed around as much of the salvageable structure and masonry walls as possible to create a pair of four- and five-story buildings with 130 units that serve as home and work space for artists and those who appreciate the arts. The large atrium allows sunlight to filter in to the common areas, serves as a gallery and exhibit space, and is conducive to community events such as open studios, film screenings, performances, and readings. Trinity Financial commissioned a public art piece, specifically for the atrium. Facilitated by the Urban Arts Institute (UrbanArts) at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, a request for proposals led to over fifty entries, ten finalists, and the concluding choice of Kim Radochia’s design.

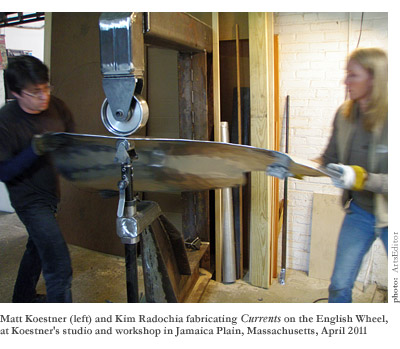

I first met Kim Radochia at Matt Koestner’s studio and metal fabrication shop in Jamaica Plain. She and Matt, a sculptor and professional welder and fabricator, had been laboring over the six- to eight-foot metal pieces, which had already been cut from flat sheets of metal. On the worktables, one flat piece had the shape of a Nike swoosh, and others looked like small pools of rainwater. To give them dimension and form, Radochia and Koestner hammered them and manually passed each one back and forth through an English Wheel, a machine in the shape of a closed letter C with two nearly-joining wheels that stretch the material and cause it to become thinner and more pliant. As the material stretched, it formed a rounded, convex surface.

Naively, I was surprised by the physicality of the work and how, while Radochia had a vision and model for the shape of each piece, much of the outcome seemed improvised. She explained that, “The minute you bring something into its physical space, it all of a sudden starts to look different and you have to just respond to what you have right at the time and make adjustments. I know from doing a lot of installation work that I might have had an idea of what I wanted to do before I went in, but when I got there with all of my materials it was really about my response to the space, the length of the wall, the light, the height of the wall, the overall physical square footage, how people are walking in, how I want it to feel to them. So it’s very esoteric and intuitive. It’s difficult to predefine anything in the field that gets to be big-scale. Things become revealed. I like that. I like the problem solving.”

Unlike most of her previous projects, with Currents Radochia did not have to problem-solve alone. With the size of the project and the technical requirements, she needed someone with more advanced metal fabrication skills and past atrium work. She had met Matt Koestner at a public art discussion series, and after receiving the commission award from Trinity Financial, she asked him to assist. As this was their first collaboration, they quickly had to learn how to work together, how to anticipate the other’s movement in the literal give-and-take of the metal through the English Wheel. Radochia easily admitted how happy she was to learn from Koestner and have help with the fabrication. Laughing, she described past projects, where she relied on her own brute force by wrapping metal around tree trunks to create curves or hooking material to the bumper of her car to stretch or twist it.

The majority of Radochia’s sculptures are ground-based. In fact, Currents is her first commissioned atrium piece and second public commission. For this reason, she admitted to being surprised at winning the award from Trinity Financial, whose representatives she really had to convince she could do an atrium piece.

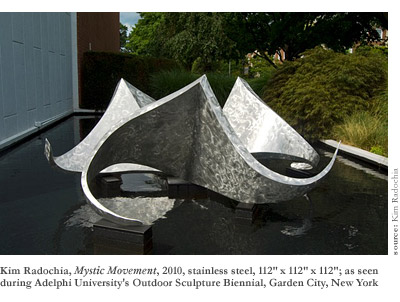

Though suspended, Currents fits into the aesthetic of Radochia’s ground sculptures, which are mostly constructed of reflective aluminum or stainless steel, sometimes including copper, wood, or glass. These forms often take curled, rounded, spiral, or swoop shapes that evoke the movement of water, rolling hills, wind, or weather patterns. Looking around her studio space in Boston’s South End, it is clear that her smaller scale art pieces—paper sculptures, smoke drawings, pieces with sticks and rocks, ink drawings called “Brush Dances”—explore similar shapes and natural themes. “I’m often taking things that I find out and about,” Radochia described. “I’m studying them closely and sometimes using the forms themselves like casts of the direct rock or trees. Other cases, I’m looking at symbology, like looking at the circle as the symbol for time… being a circle that is continuously always connected.” It sounded almost like a spiritual practice, and Radochia agreed. “It hits on a spirituality and ritualism. It’s a repeating, like saying prayers.” She showed the way she made the smoke drawings by moving consecutive pieces of paper above a flame and compared it to the way she brushes and polishes metal.

Radochia insists that her artwork defies easy categorization with its varied materials, but I saw how the recurring pieces and repeating shapes create an overall cohesion in her work, both 2D and sculptural. She expressed some tension toward what she calls her “parallel practices”—public art and fine art—and if these two seemingly disconnected practices would ever come together. The majority of her work has been fine art for galleries or private collections, but she explained how she is increasingly interested in public art for the potential of its social and political impact. When I asked what artists creating public art inspire her, her steel blue eyes lit up. She talked most excitedly about Anish Kapoor, the British sculptor famous for pieces like Cloud Gate (or “The Bean” as many people call it) in Chicago’s Millennium Park. “I believe he is looking at other dimensions of time in his work. You look into his work and there are openings and things that trick you. I’m not really there yet but I’m thinking about things like that.”

“The direction I would like to go in, in terms of public artwork,” Radochia confessed, “is doing projects that empower the landscape or a group of people in a repressed area. I need to be open to the possibility of projects anywhere, internationally even, not just here. I want to have a more activist role. What interests me in public art is the historical narrative: the people, their histories, and even the environmental history of the area.”

Perhaps what impressed the Trinity Financial deciding committee was the way Kim Radochia’s design took into account the historical narrative of Appleton Mills. Her project proposal describes how inspiration came from stories about the mill functioning in its prime. The surrounding canals were used to generate hydropower—one emptied by gravity to a lower one, which created the force to turn the mechanical wheels within the mill and thus direct the manufacturing of cloth. “Appleton Mills may not have existed without the Merrimack River,” Radochia wrote in her project proposal, “so these two structures, the man-made mill and the natural force of the river, are where the idea, Currents, started for this public art project.” The idea of water as a force that brings about the creation of other things resonated with her. She hopes that her piece inspires people of varied aesthetic tastes and reflects a thinking that generates a continual search and exploration of creative ideas.

At the Appleton Mills ribbon-cutting ceremony held on July 5th, numerous city and state elected officials, Trinity Financial employees and contractors, artists, and Lowell residents gathered to celebrate with Governor Deval Patrick what he called, “an outstanding example of job creation, affordable housing, and revitalized infrastructure in our Gateway Cities.” Under a tent in the stifling July heat, many of the elected officials recounted the cold November day of the groundbreaking gathering in 2009, when only skeletons of old brick walls stood, and to the testament of partnerships among levels of government and private investment.

Relationships, said a fine art painter and sculptor and resident of Appleton Mills, were also developing among the artists who have already moved in. They were the audience Radochia kept in mind while designing and fabricating Currents. After the ribbon-cutting presentations, everyone moved indoors to the atrium and Kim Radochia watched people look up at the skylight and the floors above and her sculpture hanging in the space. She admitted that she was surprised by how the forms—ten in total—looked after the installation, how much they blended in and floated lightly. I too was surprised. After seeing them up close, feeling their weight, and watching Radochia and Koestner bend, hammer, and polish arduously, the pieces had undergone their own transformation into something less like strong flows of water and more like whispery breaths. The sculpture felt understated, diminished almost, but I did not dislike that and perhaps only felt that way because I had seen it before I could envision the expansive space.

Trying to imagine that I was seeing Currents for the first time, I agreed with many of the resident artists, who had nothing controversial to say about the piece. One artist said it gave her an “open feeling.” Another said the forms were “wing-like, bird shapes.” He liked the idea of flight and movement because he said making art for him was all about letting one thing lead to the next, one step at a time, one idea at a time. Even with planning, art always ended up being an improvisation, and interpreting others’ art is also a process. He admitted his thoughts about Currents would likely evolve as he grew to experience the piece over time in his new home. For the moment, though, it moved him—in the direction of his new studio, away from the ceremony to work on his own art.