Secreted behind the MFA and the Longwood Medical Center, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum rests as an unassuming gem, with its labyrinthine gardens, fragrant flowers and ferns, and dark corridors. Within the special exhibition gallery is featured the work of an alumna of the museum’s Artist-in-Residence program—Laura Owens. In the spring of 2000, Owens spent one month at the museum, especially among the textiles in the museum collection, which had a great impact on her work. The collection of paintings and their arrangement in Laura Owens Exhibit: New Work offer a unique window into her time at the museum. Through them, the viewer sees a visual metamorphosis of her ideas and intense meditation on themes of reflection, with respects to outside influences, her new surroundings, her process, and her context in the history of art.

Upon entrance into the exhibit space, the viewer sees that the area where the wall text resides contains elements of what was once part of the “Chinese room,” an area designated as a private meditation space for Ms. Gardner. It was dismantled in the early 1970s, but the vestiges remain in this entryway to the special exhibition space. Between the wall texts on a wall to itself is a case containing two elephant scrolls. These pachyderms move forward through the space, but have their heads turned as if to invite the viewer on their journey. Kipling wrote in his story Toomai of the Elephants of a rogue elephant that carried a boy deep into the forests of India to witness a mystical dance—never before seen by a human. This dance Toomai experienced represented the visualization of the unseen, strange movements beyond the comprehension of those stuck in the circles of everyday thought. These elephants transport us as they did Kipling’s protagonist to worlds that defy and befuddle the linearity of external day-to-day existence. Worlds reached through reflection.

The first Owens work encountered, untitled (#1 of the exhibit), strikes the viewer as a clear, Minimalist image. The green verticals, at slight angles to one another, bisect a blue circle. A plant fashioned of collage stands to the side of those lines, which might be taken as bamboo trees in front of the moon. Near the top of the piece, a wayward petal perches between the work and the frame as a segue into the painted space from the border. It might allude to the transient nature of the creative process and the delicate paradoxical line between temporality and eternity.

The first Owens work encountered, untitled (#1 of the exhibit), strikes the viewer as a clear, Minimalist image. The green verticals, at slight angles to one another, bisect a blue circle. A plant fashioned of collage stands to the side of those lines, which might be taken as bamboo trees in front of the moon. Near the top of the piece, a wayward petal perches between the work and the frame as a segue into the painted space from the border. It might allude to the transient nature of the creative process and the delicate paradoxical line between temporality and eternity.

The simplicity of this work underlies its presence as a portal into the rest of the show. The tranquility of the blue moon draws the viewer forward, into a different space both mentally and physically. This gallery is a total departure from the warmth of the rest of the museum, with its blond oaken floors and antiseptic walls glowing with the glare of spot and floodlights. This arrangement is typical of most art spaces, as temples to self-expression.

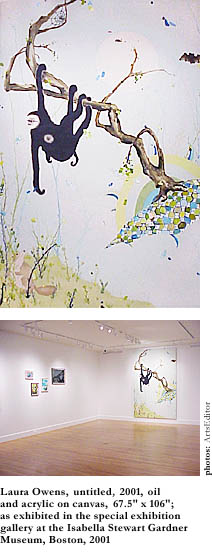

Further into the space, another untitled work (#2 of the exhibit) commands attention with its anthropomorphic monkeys stared at by a curious badger. There they hang, a mother and child—prehensile tail and arty black-framed glasses. It is the most inviting of the images, because it forms an instant simpatico with the viewer. It is instantly humorous and readable from that context.

To call attention to the work only because of the monkeys is to sell the effort short, though. The monkeys are but part of a painting that spins Asian traditions into a modern American paradigm. The tail gives that impetus away, as no monkey species outside the Americas has the curly prehensile tail that allows it to grab tree limbs and hang with ease. The way Owens has rendered the tree in the foreground, which is Asian in appearance, owes homage to the bold notes in David Hockney’s (a transplant to California, where Owens now resides) painting with its pronounced colors and chunky textures.

To call attention to the work only because of the monkeys is to sell the effort short, though. The monkeys are but part of a painting that spins Asian traditions into a modern American paradigm. The tail gives that impetus away, as no monkey species outside the Americas has the curly prehensile tail that allows it to grab tree limbs and hang with ease. The way Owens has rendered the tree in the foreground, which is Asian in appearance, owes homage to the bold notes in David Hockney’s (a transplant to California, where Owens now resides) painting with its pronounced colors and chunky textures.

The combination of these elements is clamorous and at times distracting, revealing the honesty in leaving these explorations apparent as documents of experiences encountered on her journey. One such distraction is the trippy profusion of neon colors. They emanate from a wavy, quilt-like patterned hillside that supports the gnarled tree the monkeys hang from. Also strange is the rainbow behind the tree. Its bold strokes appear to be at odds with the ephemeral moments happening in the strokes representing vegetation in the piece. The gravity of these colors overwhelms the eye. The voices of those sensual lines become ambient noise instead of lucid and uplifting notes and tone.

The stroke of grace in the work rests in the branches of the tree above the monkeys. A tiny spider’s web of ropey paint sits as a strange bass line in the midst of the fantastic chaos of symbols jostling for a clear, articulate voice. Aesthetically, the web does not speak of masterful technical execution, but as metaphor and allusion to the creative process. As such a note, it is vital.

The web references the contest between Arachne and Athena. This was the ultimate competition between mortal and immortal. Arachne was well known for her talents as a weaver. Her patron, Athena, challenged her to produce the most transcendent piece on a loom. Both produced fine tapestries: Athena’s depicted the glories of Olympus, while Arachne’s chronicled the foibles and peccadilloes of the gods from a more tongue-in-cheek approach. In her rage at Arachne’s disrespect, Athena transformed her into a spider.

Like Arachne, Owens spins her own web of imagery, humorously ribbing conventions of painting with the ways she applies paint in this work—thin washes interspersed with gooey slashes of color. She has also liberally acquired symbols from other cultures (e.g. the badger and moon from Japanese ink paintings.) These explorations reflect the ways she attempts to reconcile her standing in the midst of greater artistic currents, as in those Asian ones and the slippery slope of Modernism. Once again, with the moon imagery there rests an allusion, which represents reflection and inner journey.

A third untitled work (#3 of the exhibit) pulses with the most intense color of any in the show. A deep series of blues offers a clearer portrait of Owens’ proclivities. A row of posts connected by a cord recedes into a seething black background of rich, expressive marks. Impressions of bats as faint and eternal as faces in clouds populate the foreground. Bats bring fortune in Chinese lore; they are the only mammals to use sonar—sight through the unseen. There is a strong progression in her imagery and suggestion with this piece. The sparse nature of this work in comparison to #2 of the exhibit allows the piece to express itself in a way that is less frenetic. Also appealing is the conviction with which she painted. The strokes are more of the moment; the colors have more punch. These elements work in concert to illuminate her total presence in the piece. The viscerality of true emotion shines and attracts the attention of the audience by virtue of its rawness.

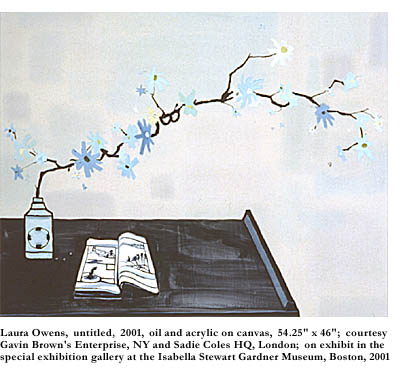

A compelling marriage of her humorous whimsy and committed mark making is the untitled work (#9 of the exhibit) on the back wall of the space directly across from the monkey painting. It reflects the most successful union of Asian and Western themes coursing through Owens’ work. The composition is deceptively simple and flat. She adheres to conventions Japanese artist Takashi Murakami alludes to when he describes Japanese Master paintings: “…Everything is in focus.”

In the foreground on a table are three pens, a sketchbook, and a vase holding an impossibly long branch from a flowering tree. They are rendered with grace garnered from the strugglings of earlier works in the show and are the more beautiful for the audience’s being allowed to witness the maturation process. The lines have a refined spontaneity echoed in the accumulation of expressive petals on the flowering branch. The arrangement of the painted space complements the sensuality of the individual lines cohesively. Subtle color washes of blue rectangles appeal to contemporary sensibilities with their immediate references to Mondrian and the sleekness of mid-century modern design. Within that homage is the deeper connection to the Asian screens accenting the corners and lentils of the main galleries in the museum, with their clear geometries and distilled visual punch.

The cohesive subtlety of this painting moves beyond the circus tricks of other works in the show. Foremost of those tricks is the overt reference to Van Gogh in her “sunflower collage.” In that piece, Owens paints sunflowers and places collage over a reproduction of one of his sunflower paintings. Her voice is refined and convincing in #9 of the exhibit. The painting represents the most fitting document of the reflective processes involved with some manifestations of personal expression.

As an exhibit that depicts the wanderings of an artist on paths of exploration in the midst of new surroundings in Boston and at the museum, Laura Owens Exhibit: New Work enlightens viewers with a glimpse of that path. The layout of the show reflects this process, which can defy reason and coherence as a document to self-examination. However, the arrangement of the paintings and use of wall space outside of the process/experiential mindset is helter-skelter. Many in the gallery were disoriented by the blank wall—designed “to allow your brain a break” as stated by the artist in a recent interview. Owens raises many questions, as a true trickster should. The arrangement of space in the gallery and in her paintings jostles minds from the known artistic cannon—from what a gallery is “supposed to look like” and what represents pleasing composition within a piece. This pushing of sensibilities is effective given the context of the space.

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum is a kind of time capsule preserving the vision of a wealthy art collector as well as some of the most glorious examples of classicism. Thoughtful consideration of the total show reveals these sensual folds and lavish attention to every detail contained in the experience. Laura Owens demands much of her audience. Should the viewer assume this responsibility, many lessons and treasures await, as those treasures Toomai of the Elephants found, because he took the time to open himself up to experiences outside the circumscribed realm of his perceptions.