In January of 2002, when the Human Rights Watch International Film Festival played in Boston, a local film critic called American director Stephanie Black’s documentary Life and Debt “lucid in exposing the culpability and heartlessness of international corporations,” but added that “Black’s otherwise fine documentary grates when it indulges in a self-righteous voiceover.” That controversial voiceover, adapted from Jamaica Kincaid’s text “A Small Place,” is indeed problematic, but it is intentionally so. The words are harsh, directed at an American public largely blind to the goings-on of other countries. Now more than ever—with the imminent reconstruction of Afghanistan and the foreign policy wake-up call of recent months—the time is right for a film like Life and Debt, which promotes the awareness that the U.S. and the rest of the developed world share a responsibility in the effects and aftereffects of global economic strategies.

Life and Debt, which returns to Boston area screens from February 22nd – 28th at Harvard Square’s Brattle Theatre, takes as its subject the island of Jamaica and its financial struggles in the climate of globalization. The film uses a unique style of documentary storytelling, which unfolds before us in much the same way that the concepts became revealed to Black during her stay in Jamaica while working on this film and her previous documentary effort, H-2 Worker, which dealt with migrant sugar cane workers in Florida. “When you come to Jamaica as a tourist,” offers the voiceover narration as an airplane touches down on the island, “this is what you will see.” As the narration weaves in and out of the film, we are ultimately shown things that the typical tourist (and the metaphorical tourist—the viewer) does not see in Jamaica—the things beyond the hotels on the beach and the McDonalds on the Queens Highway, like the workers whose everyday lives are affected by the policies of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), who in the name of globalization have constructed a system that leaves Jamaica helpless to promote any internal economic growth. The tourist’s vision of Jamaica is separated from these realities, as exhibited in the film by the recurring image of a tourist’s palm on a vehicle window (a bus at one point, another a plane), which becomes the glass divider between the spectator and the outside world. Another portion of the film shows the dichotomy that exists by flashing back and forth between Jamaican workers in a repetitive box-pitching motion and tourists at some sort of aerobic dancing class. In this place where an incompatible and in-competable international market has so devalued domestic product, tourism is a leading field of employment. “Tourism in Jamaica,” comments Black, who spoke with ArtsEditor® in late January, “is a service industry that requires the reinvention of the country to its visitors in its representation of itself.” Accurate representation of the economic plight of Jamaica is what Life and Debt strives to do, and in doing so it serves as a case study for a dilemma that has plagued so many other struggling nations.

Life and Debt, which returns to Boston area screens from February 22nd – 28th at Harvard Square’s Brattle Theatre, takes as its subject the island of Jamaica and its financial struggles in the climate of globalization. The film uses a unique style of documentary storytelling, which unfolds before us in much the same way that the concepts became revealed to Black during her stay in Jamaica while working on this film and her previous documentary effort, H-2 Worker, which dealt with migrant sugar cane workers in Florida. “When you come to Jamaica as a tourist,” offers the voiceover narration as an airplane touches down on the island, “this is what you will see.” As the narration weaves in and out of the film, we are ultimately shown things that the typical tourist (and the metaphorical tourist—the viewer) does not see in Jamaica—the things beyond the hotels on the beach and the McDonalds on the Queens Highway, like the workers whose everyday lives are affected by the policies of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), who in the name of globalization have constructed a system that leaves Jamaica helpless to promote any internal economic growth. The tourist’s vision of Jamaica is separated from these realities, as exhibited in the film by the recurring image of a tourist’s palm on a vehicle window (a bus at one point, another a plane), which becomes the glass divider between the spectator and the outside world. Another portion of the film shows the dichotomy that exists by flashing back and forth between Jamaican workers in a repetitive box-pitching motion and tourists at some sort of aerobic dancing class. In this place where an incompatible and in-competable international market has so devalued domestic product, tourism is a leading field of employment. “Tourism in Jamaica,” comments Black, who spoke with ArtsEditor® in late January, “is a service industry that requires the reinvention of the country to its visitors in its representation of itself.” Accurate representation of the economic plight of Jamaica is what Life and Debt strives to do, and in doing so it serves as a case study for a dilemma that has plagued so many other struggling nations.

The music in Life and Debt, which is collected on a Tuff Gong Records soundtrack album (release date: February 5th, one day after Bob Marley’s birthday), plays a key role. Consisting largely of reggae artists—with several of whom Black has worked previously in music video format—the songs were chosen, says Black, because of a “special meaning” they help bring to the film, be it lyrical or emotional. Going one step further, proceeds from the sale of the soundtrack album, which also features excerpts from the film (“it’s a CD with attitude,” jokes Black), will go toward URGE, a non-profit world relief organization founded by Ziggy Marley and the Melody Makers. Legendary Marley patriarch Bob’s song “One Love” is the most frequently heard tune in the soundtrack (in 4 different versions); the use of the bouncy, optimistic tune contrasts with what we see on the screen, showing the inherent failures behind the idealistic notions of One World and One Economy. Frequently, the happy sound of reggae music is used to speak of injustices and hardship, a peculiar irony that is utilized to its fullest in the film. Life and Debt is framed by reggae singers Buju Banton and Yami Bolo, each walking down Jamaica’s populated streets with a song on their lips with a natural feel that does not betray their superstardom. “I was interested in not situating them in a stage setting, because that’s where this voice is coming from; this music is for the most part coming out of the ghetto, and it is the people’s voice.” Another voice heard in the film, but not on the soundtrack album, is that of Jamaican-raised calypso star Harry Belafonte, whose classic “Banana Boat Song” lends an extra dimension to the description of Jamaica’s lagging banana industry, wherein an exclusivity of trade with the British, from whom Jamaica gained its independence in 1962, has irretrievably damaged the Jamaican economy. The lessons of Life and Debt are not easily swallowed, but the soundtrack acts as a lubricant to help ease these concepts down the viewer’s throat.

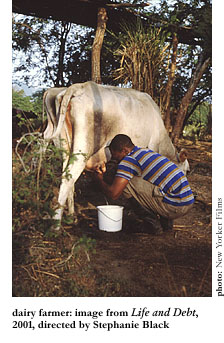

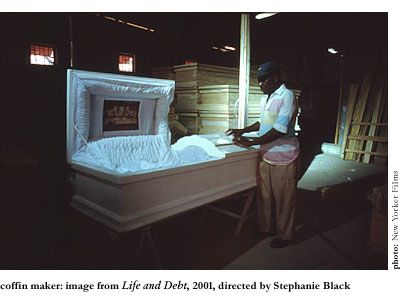

On one level (for this clever film works on several), Life and Debt is an example of how theories do not always translate into practice. Globalization, in the eyes of much of the western world (which also happens to control the bulk of the international market), seems a benevolent gesture of market sharing to enable growth in smaller and underdeveloped nations. Unfortunately, in reality the end result is quite different, particularly in Jamaica where imported produce undersells its domestic equivalent, and imported powdered milk comes so cheaply that Jamaican dairy production is quickly dying (the film shows a farmer pouring the bulk of his collected milk down the drain in a particularly heart-wrenching and effective scene). Black is fortunate to have apologetic testimony from former Jamaican Prime Minister Michael Manley, who in the 1970s was forced to sign for many of the loans that resulted in the current economic crisis, and shocking interviews revealing the plight of non-unionized factory laborers in Kingston’s “free trade zones.” Through creative and manipulative storytelling, Black reveals how all of this has forced the country into great debt and an unnatural dependence on the rest of the world that will result in making Jamaica incapable of supporting itself on its own two legs.

On one level (for this clever film works on several), Life and Debt is an example of how theories do not always translate into practice. Globalization, in the eyes of much of the western world (which also happens to control the bulk of the international market), seems a benevolent gesture of market sharing to enable growth in smaller and underdeveloped nations. Unfortunately, in reality the end result is quite different, particularly in Jamaica where imported produce undersells its domestic equivalent, and imported powdered milk comes so cheaply that Jamaican dairy production is quickly dying (the film shows a farmer pouring the bulk of his collected milk down the drain in a particularly heart-wrenching and effective scene). Black is fortunate to have apologetic testimony from former Jamaican Prime Minister Michael Manley, who in the 1970s was forced to sign for many of the loans that resulted in the current economic crisis, and shocking interviews revealing the plight of non-unionized factory laborers in Kingston’s “free trade zones.” Through creative and manipulative storytelling, Black reveals how all of this has forced the country into great debt and an unnatural dependence on the rest of the world that will result in making Jamaica incapable of supporting itself on its own two legs.

The film does an excellent job of consolidating complex ideas into an easily digestible format, and Black has enabled this by interviewing several of the people actually affected by the tariffs and sanctions imposed by the global corporations. Helping to tell the story are three Rastafarian wise men discussing politics around a fire, while very noticeably not surrounded by the ganja with which they are usually depicted in American films (“I was definitely interested in not fulfilling that stereotype,” says Black). Giving screen time to a slick educator on the subject matter—Dr. Witter, Professor of Economics at the University of West Indies—doesn’t hurt, either. Black, whose credits include the production of several shorts for Sesame Street, is skilled at parlaying information in a memorable and often entertaining way. Life and Debt was in the making for the better part of ten years, and although some of the movers and shakers have changed—including IMF Deputy Director Stanley Fischer, who stepped down—the problematic policies remain.

In the end, Black wishes us to ruminate “the question of responsibility” and gain a new understanding of the negative aspects of globalization, especially now that IMF and World Bank policies in other countries are making the news. “With countries like Argentina,” says Black, “we (Americans) don’t hear about it until it’s reached the point where people are killing each other in the streets, but we don’t hear about all the news stories along the way that led to this point.” But will there be, can there be change after this film? “My hope is that the increased transparency of these institutions will catalyze reform,” says Black. The last thing she wants, however, is to scare viewers away from visiting Jamaica or other countries because of the film’s unsympathetic portrayal of the generic tourist. “A lot of people watching the film think that I’m trying to discourage them from visiting Jamaica, which is the complete opposite of my intent. Jamaica is one of the most magnificent places I’ve ever been to in my life,” and she feels that everyone should take an opportunity to experience its beauty and culture.