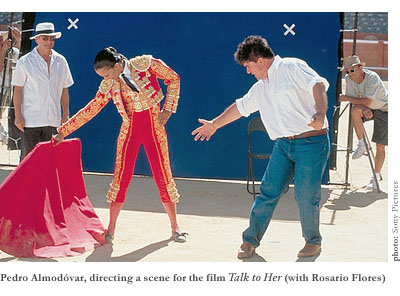

“They must have made a mistake.” This was Spanish director Pedro Almodóvar’s initial reaction to the announcement of the 2003 Oscar nominations. His perplexity was understandable, too. After all, why should The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences have nominated his latest film, Talk to Her, in both the Best Director and Best Original Screenplay categories when the Spanish Film Academy hadn’t even deemed it worthy of submission as Spain’s candidate for Best Foreign Language Film (choosing instead Fernando León’s stark tale of unemployment, Mondays in the Sun)? “They made a mistake,” repeated Almodóvar, when asked about the discrepancy at a subsequent news conference—but this time he was talking about the Spanish Film Academy.

The Spanish Film Academy must have thought that this unlikely boy-meets-girl love story did not stand a chance in formulaic Hollywood. And one cannot help but empathize with them, for the love story is of the disturbing and surreal kind. Boy spies girl through opera glasses from mother’s window. Boy stalks unwitting girl for a few weeks until girl gets hit by a car and falls into a deep coma. Boy takes nursing course and conveniently takes conscientious charge of, amongst other things, cleaning up the blood every time she gets her period. Extra nursing services include chatting to her endlessly about anything and everything (including the size of her breasts) as well as delivering intimate full-body massages, which the camera records in full detail. This nurse becomes friendly with an Argentine journalist whose girlfriend, a female bullfighter terrified of snakes, is also in a deep coma in the room next door. The devastated journalist is fascinated and soothed by the nurse’s apparently cheerful acceptance of his beloved’s hopeless condition—even though he, the journalist, is never entirely convinced of the sense of talking to his girlfriend as if she were still perfectly sentient (from which advice the film takes its name).

But then events take a decidedly dark turn. Interrupting the narrative flow is a hilariously bizarre snatch of a pseudo-1924 silent movie in which a shrinking man throws off his clothes and crawls into the vagina of his full-size sleeping girlfriend, thus giving her a phenomenal orgasm. This seemingly random black-and-white whimsy is in fact supposed to symbolize the fact that, back in the present, the boy has made his comatose “girlfriend” pregnant (an act, based on a true story, that even the unrestrained Almodóvar apparently regarded as being too disturbing to depict literally).

What, one might well ask, can the Academy have been thinking in nominating such an emphatically foreign film in two categories normally monopolized by Hollywood blockbusters?

Yet these nominations for Almodóvar haven’t come entirely out of the blue. The start of America’s peculiar love story with Almodóvar dates back to 1988, when his Academy Award nomination for Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (a hysterical comedy about intermingling love triangles bathed in narcotic gazpacho) first brought him—and Antonio Banderas—to international prominence. Several films followed, which were invariably welcomed by both critics and the general public. Eleven years later, All about my Mother (in Almodóvar’s words “a fable about maternity, female solidarity, and women’s natural ability to pretend and perform”) was awarded a Golden Globe and, a few months later, the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar.

So who are America’s Almodóvar fans? From what I can see, they don’t always seem to be social outcasts. In fact, they tend to be pretty mainstream people that look and behave normally—they’re typically married, with no known lovers or unusual sexual inclinations; they even have children sometimes. My neighbor has seen Talk to Her. Yet I can’t imagine us having a conversation about different brands of vibrators as we met outside the house shoveling yesterday’s snow. My co-worker actually loved Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, but I suspect that my questioning of how her recent pregnancy has affected her sexual life would not go down very well. They are the same kind of people that recently found Amélie delightful, or would sit through The Pianist, Gangs of New York, or My Big Fat Greek Wedding with a box of popcorn at their side. So how do these fans fit in Almodóvar’s world? How do they actually see his world and what do they get out of it if, as it looks at first glance, they have nothing in common with it?

In another unusual (yet less satisfying) exercise of incredible shrinking, I will attempt to reduce this world to a paragraph, starting from the very beginning: with a young Pedro Almodóvar leaving his deep-Spain La Mancha and his stale Catholic upbringing for an administrative assistant’s job with the Spanish National Phone Company in Madrid, which allows him to buy his first Super-8 camera. Franco’s dictatorship is over and a colorful, deliberately distasteful, and generally excessive cultural Renaissance is flourishing in the city. Almodóvar’s first film, Pepi, Luci, Bom, today regarded as a Spanish ’80s classic, captures the carefree energy and decadent freedom of this movement. In subsequent films, Almodóvar enriches his characters psychologically and provides them with complex backgrounds. His stories get ever more intricate, and more importantly, he decorates them with a key ingredient that still defines and identifies Almodóvar’s style: the revival of obsolete Spanish themes, such as bullfighting, the Catholic Church, death, and over-the-top emotionality. While these national icons retain their emotional load, they look slightly artificial and out of place. The final product resembles a soap opera in its format, but one that teeters on the edge between farce and drama.

In Spain, Almodóvar’s formula has had a profound cultural effect—it has contributed to the development of an alternative culture that looks back sympathetically on these traditional icons. This Spanish-flavored post-modernism also celebrates naiveté, tackiness, and ignorance (a dying legacy of the cultural isolation of the Franco era) in a country that today is, in many aspects, indistinguishable from other modern European nations.

Most Bostonians are probably unaware of the cultural and historical peculiarities against which Almodóvar’s films play out. No doubt that explains why they laugh when I cry (and vice versa) whenever I watch an Almodóvar film here. However, any nationality can easily give in to the appeal of the deranged soap opera plots. In fact, their particular prominence in All about my Mother and Talk to Her may well be the reason why Almodóvar has also begun to reach a more mainstream, less intellectual audience in Spain. And ultimately, not even intellectuals are free of the mundane soap-opera-watching instinct; Almodóvar simply provides a sophisticated, critically acceptable way to deliver the same narrative formula underlying such products as Dynasty, ER, or Friends.

The result is that Almodóvar provides the average American with an excellent deal: their usual entertainment formula, spiced up with any number of weird characters and unlikely situations. Why would you want to watch Rachel wonder whether she should finally marry Ross when you could have her come out of a stormy relationship with a terrorist Shiite, only to be kidnapped by her next-door neighbor—a man who, despite his possession of the biggest penis known to humanity, has never dared to talk to any woman besides his mother, with whom he lived until she became a TV star and left for America to try her luck on a religious TV channel? I know which I would choose. Add to the allure a sunny, colorful backdrop, a few cathartic rows, and a cast of beautiful actors and actresses who regularly take off their clothes and have great sex—and how could anyone resist?

Almodóvar’s own explanation for his international success, though, is rather more mystical. As he confessed in a recent self-interview, he asked the Brazilian sea goddess Yemanyá to make Talk to Her rise above conservatism and old-fashioned prejudices to be successful. (“I hope the days of political correctness are gone; otherwise I’d be doomed.”) And evidently the goddess heard him. Unfortunately, though, the great director did not see fit to quit while he was ahead. He explains, “I’ve also asked her, amongst other things, for the end of trash TV and the current trend of shooting from behind the actors, which makes the audience sick. I’ve also asked her for a son, and for a new hairstyle—I’m sick of the usual one. I don’t want to gain any more weight. In fact, I want to lose some. And I want her to bring back the stupid optimism of the early ’80s—without the drugs.” Well, we’d better let the goddess get on with it—although I could definitely help with the haircut.