Far from the so-called reality that clutters today’s network television transmissions, the tangible, heartfelt veracity found in the music of Damien Jurado is concerned with a purer form of reality—one dealing with real lives, real people, and real emotions. Apparently a big part of being real, for Jurado, is also being real unpredictable. Having made a career of frequently switching stylistic gears, the Northwestern singer-songwriter recently surprised everyone by releasing his strongest and simultaneously most subdued album to date, Where Shall You Take Me?.

An urban folksinger whose music exudes a corporality as equally hefty as his physical stature, Jurado’s songs are tiny first-person narratives from another man’s shoes and snapshots taken from various lives, with attention to the minutiae. Navigating territory similar to Bruce Springsteen’s backstreets, Tom Waits’ backrooms, and John Mellencamp’s back porches, but with the more intimate reflection of early Jackson Browne, Jurado’s musical storytelling brings to life characters who, however briefly glimpsed, come across in three dimensions and whose struggles, both small and large, are fleshed out with an intense physicality.

Jurado is frequently accused of dwelling on the melancholy (one critic went so far as to say that Jurado puts the “dour” back in troubadour), and while he certainly tends towards somber themes, “ruminative” may be a better term to use than “depressing” when describing Jurado’s music. The pain and affliction in his songs often seems posited to effect, through experience, a sort of emotional or spiritual purification—like the “razor blade that cuts you clean” in the lyrics of his song “Amateur Night”—that helps to make the process of listening more like the sharing of knowledge and understanding. At the same time, and to the same end, Jurado purveys an affectionate respect to folk and American song traditions, composing in a format rooted in and reminiscent of older styles and structures, like his singer-songwriter contemporaries Connor Oberst (Bright Eyes), Will Oldham (Palace), and Jason Molina (Songs: Ohia).

Jurado is frequently accused of dwelling on the melancholy (one critic went so far as to say that Jurado puts the “dour” back in troubadour), and while he certainly tends towards somber themes, “ruminative” may be a better term to use than “depressing” when describing Jurado’s music. The pain and affliction in his songs often seems posited to effect, through experience, a sort of emotional or spiritual purification—like the “razor blade that cuts you clean” in the lyrics of his song “Amateur Night”—that helps to make the process of listening more like the sharing of knowledge and understanding. At the same time, and to the same end, Jurado purveys an affectionate respect to folk and American song traditions, composing in a format rooted in and reminiscent of older styles and structures, like his singer-songwriter contemporaries Connor Oberst (Bright Eyes), Will Oldham (Palace), and Jason Molina (Songs: Ohia).

In his quest for the genuine, and in seeking the details overlooked in our everyday lives, Jurado even took some time off from songwriting and played armchair sociologist with an album of “found” sound collage, Postcards and Audio Letters (and a planned follow-up entitled Listen to this Life), which consists entirely of audio of people speaking, culled from old cassettes Jurado stumbled across in thrift stores. Taped love letters, answering machine messages, and the like were reshaped from one-way epistles and built into a collective conversation. It’s similar in spirit and motivation to Paul Simon’s “field” recordings of the elderly, “Voices of Old People,” from Simon and Garfunkel’s 1968 Bookends album, but whereas Simon presented, via spoken confessionals, the way we think and feel (specifically in our autumn years), Jurado’s Letters is more subversive and revelatory in exposing something about the way we communicate those thoughts and feelings.

There is a surprising range in Jurado’s recorded output. The sound of his albums, by turns, has gone from soft to loud and back to soft again. Part of the credit for this variety could be attributed to the shifting array in Jurado’s choice of producers, which have included veteran engineer Steve Fisk, Pedro the Lion frontman David Bazan, and latter-day power-popper Ken Stringfellow (of Seattle legends The Posies), but there’s no denying that Jurado is the chief architect of the variety of the shape and sound of his craft, which he began recording to cassette at home (cassettes much like those he used in creating Postcards and Audio Letters) many years ago.

Jurado’s 1997 debut for Seattle’s Sub Pop records, Waters Ave S, is littered with his “real people.” It includes tales of broken relationships (“Independent”), marriages gone wrong (“Wedding Cake”), war widows (“Treasures of Gold”), unrequited love (“Halo Friendly”), and other stories of characters that are dancing and laughing through the trials and tribulations of life. The catchy country pop of “Letters and Drawings” and the slide-guitar-driven “Honey Baby” power 1999’s superior follow-up, Rehearsals for Departure, which garnered Jurado a new audience.

Ghost of David, released in 2000, is a hauntingly stark collection of tableaus that focuses gravely on the dark quietude of death. Ghost has a stripped-down, back-to-basics approach and enables Jurado to bare himself—and his characters—in a raw, unnerving fashion. But even the heaviest themes have their light spots: “I have seen the brighter side,” Jurado sings, in a Monty Python’s Life of Brian moment, “of the roads that lead to Hell” (from the positively bleak composition “Desert”).

Ghost of David, released in 2000, is a hauntingly stark collection of tableaus that focuses gravely on the dark quietude of death. Ghost has a stripped-down, back-to-basics approach and enables Jurado to bare himself—and his characters—in a raw, unnerving fashion. But even the heaviest themes have their light spots: “I have seen the brighter side,” Jurado sings, in a Monty Python’s Life of Brian moment, “of the roads that lead to Hell” (from the positively bleak composition “Desert”).

Jurado’s next album, 2002’s I Break Chairs, was recorded with a full backing band christened Gathered in Song, and marked a stylistic shift to a stronger, more assured, even occasionally joyous, rock-oriented sound. Chairs kicks off with the rollicking “Paperwings,” a song that sets the bittersweet tone for the album by expertly combining polarized images of suicide (“Here’s a noose for your head”) and a celebration of vitality (“Go put on your brand new dancing shoes”).

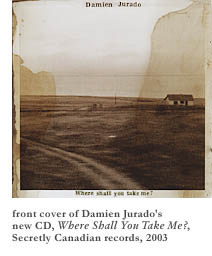

With Where Shall You Take Me?, his first album for Indiana-based Secretly Canadian records, Jurado returns to the bare soundscapes of Ghost, this time injected, however, with more solidity and resonance. It might just be that recording with a full rock ensemble on the I Break Chairs album allowed Jurado the freedom to step back again with his newest work, which is in many ways his sparsest and most subtly textured, but clearly he has kept handy in the cupboard the best ingredients of Chairs, to be applied wherever necessary for added seasoning. The new album finds Jurado’s songwriting to be considerably matured—toned, honed, and refined, without lacking for the bite of his earlier work. Funny, then, that the first track on his most professional record yet should be called “Amateur Night.”

“First came the screams and blood on the floor.” Those harsh words, delivered with a hush, open the new album, and are a prelude to an eerie meditation on the twisted mind of a fellow who claims he’s “not an evil man/ I just have a habit I can’t kick.” Following that is “Omaha,” an appetizingly tuneful slice of Americana. Next, “Abilene” lilts like some old New England colonial ballad rediscovered by Richard and Mimi Fariña and shared with friends backstage at the Newport Folk Festival. Then, wake up, a chiming electric guitar jangle introduces “Texas to Ohio,” the most overt remnant of the previous, rockier-sounding album, and the song itself a bitter remnant of a past relationship that examines the distances found in the time and space between us.

Windows are frequently utilized in Jurado’s songs as symbols of vision and framers of reality. In a song plainly called “Window,” where Jurado is joined sweetly by duet vocalist Rose Thomas, the window is an opportunity for the light to shine through in a pretty little secularized spiritual. In “Intoxicated Hands,” a gentle, misplaced drum machine struggles vainly to keep in step, but falls strangely out of place in a sobering account of an infidelity clouded by alcohol.

Throughout Where Shall You Take Me?, there is immeasurable value placed on the simplicity of the songs, which lends itself best to the musical and lyrical economy found in both “I Can’t Get Over You” and “Matinee,” as well as the straightforwardness of the unadorned offering “Tether” and the tender plea of the album-closing “Bad Dreams.” When Jurado pushes forth the simple things in his songs, it brings him that much closer to the truth, the reality of it all.

Throughout Where Shall You Take Me?, there is immeasurable value placed on the simplicity of the songs, which lends itself best to the musical and lyrical economy found in both “I Can’t Get Over You” and “Matinee,” as well as the straightforwardness of the unadorned offering “Tether” and the tender plea of the album-closing “Bad Dreams.” When Jurado pushes forth the simple things in his songs, it brings him that much closer to the truth, the reality of it all.

A spring tour recently brought Jurado to T.T. the Bear’s Place in Cambridge, Massachusetts for an evening of music and spoken word, joined by the mellow songcraft of Secretly Canadian labelmate Dave Fischoff and the amusing, sharp, colloquial witticisms of author Adam Voith, who read letters written by fictional characters from his novel Stand Up, Ernie Baxter: You’re Dead (TNI Books). “When did the bridge between music and writing fall?” Jurado asks rhetorically in his Web site’s tour log, alluding perhaps to the title of Voith’s earlier book, Bridges with Spirit. “It is my goal on this tour to help build that bridge. At least a little.”

The progressive pairing of word and song provided an intriguingly unique entertainment most unlike the usual fare at the venue, with fans seated quietly on the floor space typically reserved for trampled cigarette butts and spilled beer. Fischoff and Voith delivered their respective songs and readings valiantly, despite the heavy rumbling of a performance by metallic, bass-propelled band Jucifer on the downstairs stage of neighboring club The Middle East. With the vibrations from below threatening to shake the very building to its foundation, Voith copped an “if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em” attitude with mock-defeatist, humorous asides that served as somewhat of a salve for Jucifer’s noisy distraction.

Jurado took the stage next, a lone soul hunched over his electric guitar. Between-song banter was kept to a minimum at first, as Jurado quickly strummed through crowd-pleasing highlights of his back catalog, which performers refer to as “oldies.” As Jurado pulled out some new songs, he opened up a bit—albeit in a clipped mumble—but only to reveal how bummed he was about the fact that his acoustic guitar was broken (apparently due to an unfortunate circumstance of airline clumsiness), and thus frustratingly (but absolutely unnoticed by the adoring audience), his tunes weren’t working out as well on the electric. After a moving performance of the late folk icon Nick Drake’s “Fly,” Jurado explained that it’s a favorite of his young son Miles—more favored by the child, in fact, than any of Jurado’s own songs, which, when plucked out at home, are met with the toddler’s intemperate distaste and a request to “Play ‘Fly,’ Daddy…”

Reserved stage demeanor notwithstanding (since, after all, it is part of the charm that endears him to his core group of fans), Damien Jurado has carved out a strong presence in a little world that straddles the folk community and the underground rock community. The genre-transcendent nature of Jurado’s music has proved to be a boon, giving him an opportunity for broader appeal. Which is not to say that in his aspiration Jurado could, or even should, ever hope that “this country will know me by name,” as proclaimed by the narrator of the song “Omaha,” but one can be sure that Jurado will continue looking for real voices to reflect in his work, wherever next it shall take him.