Most people in this sophisticated British colony of Massachusetts know that an English “picturesque landscape” style of gardening dominated public American park designs in the late 19th Century, when spare space was being parceled out and it was still too early to pave the entire paradise. And most know that Frederick Law Olmsted is the landscape architect most known for instituting that style all over the country. Olmsted’s pastoral greenswards, made to look like settled English sheeplands bordered by shady woods, have survived massive development in Seattle, Louisville, and New York, and are downright ubiquitous in Boston. But not everyone realizes that Olmsted—or the firm in which he was a formidable partner, anyway—also designed the campus of Smith College in Northampton. As it happens, Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) was born around the time that Olmsted was working on Smith. Which, in a circuitous way, seems to be one reason Virginia Woolf: A Botanical Perspective, an exhibit of enlarged images from Woolf’s family albums, is on display at Smith College through September 30th.

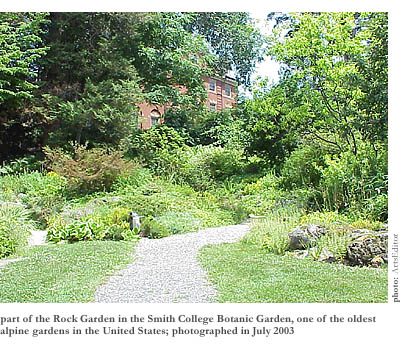

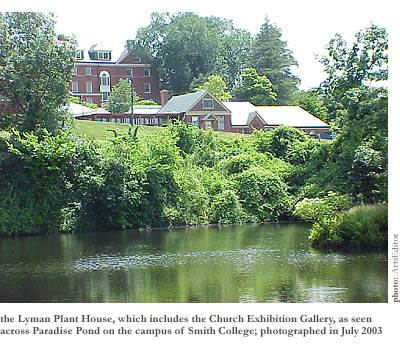

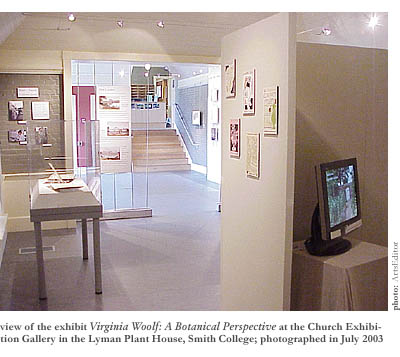

Though not a blockbuster in any sense of the word, it’s a pretty harmless exhibit, worth stopping by to see on the way back to the Mass Pike from dropping the young student off at UMass Amherst, hanging out at Tanglewood, or camping in Vermont. First you’d have to find the exhibit, though. It’s in the very small and tidy Church Exhibition Gallery, which is located in the Lyman Plant House, near the front desk in the administrative area of what is essentially a system of greenhouses way down at the back border of the campus, just above Paradise Pond and the popular foot trail along the Mill River. The exhibit was developed in conjunction with Smith College’s conference Woolf in the Real World, which occurred this past June and included, among other things, panel presentations by over 160 scholars from 7 countries.

Consisting mostly of several small groupings of black and white photographs of Woolf and/or Woolf-related country places (supplemented by captions of quotes from Woolf’s writings or of biographical observations from the curator), the exhibit provides, in a very quiet 45-minute tour, material for a garlanded contemplation of her writing. The walls of the exhibit take you not quite exactly in chronological order from English country paradise to English country paradise of Virginia Woolf’s life. Just when you think you’ve seen the fanciest summer spread this side of the Crane estate in Ipswich or the Lyman manse in Waltham, along comes another series of photos from some spectacular other settlement that looks like it sprang from the pages of an 18th Century British comedy-of-manners novel. The manicured fairway between the rows of plane trees where the noble young lord would court the maiden and her parasol. The stately stone edifice—”house” is far too humble a word—with marble ballroom floor and classical statuary. Places you’d expect to be named Windmere and Downsworthy.

The exhibit starts at the entrance, understandably enough, with images of the young Virginia Woolf. On either side of the portal to the gallery hangs a photo of the modernist master as a gangly youth of high and homely privilege, horsy aristocratic English face and all, outside her brick childhood summer home, known as Tolland House, in the Cornwall district of southwestern England. It’s 1894, Virginia is 12, and that’s her, in the midst of four or five family members, stooping to pet a dog. Her mother, her sister (Vanessa Bell—illustrator of her stories), and her brother (Thoby Stephen) look this way on that bright summer day, with roses climbing a trellis near a door to the manse and a greenhouse absorbing the rays in the background. A passage from Woolf’s early autobiographical prose waxes fragrantly of the symbiotic relationship between apples and bees, making viscous golden honey and the euphoric nature poetry of Keats and Shakespeare come to mind. In the autobiographical excerpt, Woolf remembers her natural experiences at Tolland as “rapture rather than ecstasy.” Surprisingly, though, not a word about this haven providing the verdant setting for the purportedly autobiographical novel To the Lighthouse, which features a doting mother and disheartened wife spending a 180-page day trying to appease her young son’s urge (against her husband’s discouraging words) to take a picnic out to the lighthouse across the bay from their bucolic summer place in the Hebrides of Scotland.

In the series of pictures of Kew Gardens in London (admittedly not the private property of the Stephen family she grew up in) you’ll find more lush, if black and white evidence of the “picturesque landscape” design. A flowing mass of bushes borders a placid lily pond, and a rapturous or perhaps ecstatic young damsel of independent temperament brazenly twists her torso and lovely neck this way from her contemplative spot on the grass. (Women’s suffrage is on its way, and Virginia Woolf is about to write things that will make her a heroine of the Second Wave of the feminist movement.) In the caption, a passage from Woolf’s short story “Kew Gardens” celebrates “the first red water-lilies I’d ever seen. And suddenly a kiss, there on the back of my neck,” as well as the autobiographical memory of going to Kew to paint “orchids and cranes among wild flowers, a Chinese pagoda and a crimson crested bird.”

Near to the Kew Gardens grouping of images and text are featured early editions of such Woolf works as The Death of the Moth and The Captain’s Death Bed and Other Essays, which were published by the press (Hogarth) that Virginia founded with her husband, Leonard Woolf, in the Bloomsbury district of London that is synonymous with their names. On the covers and in the margins of the interior pages you can admire the illustrations of Virginia’s sister and lifelong companion, Vanessa Bell. Are those the looping tendrils of morning glories with heart-shaped leaves that enwreathe the title on the front, and are those the climbing vines of clematis that illuminate the margins of a page? And why did it never occur to you how very important the green world was to this writer? Were you not reading closely, or were Woolf’s natural images so subtly woven into the fabric of her prose, like spruce roots tying together the birch-bark flanks of an Abenaki canoe, that you just never paid it that much mind?

Given Woolf’s famously tormented psyche, you can’t help but wonder if the natural world didn’t offer her hope for release into a more peaceful world outside of herself. A reading of her fiction might suggest the same. Her disarmingly present characters, portrayed mid-struggle with little hope of making it out alive, have the seemingly private streams of their individual consciousnesses fed by tributaries that flow through the other characters as well. Her sentences let their tangential subordinate clauses trail off a little, like shade-seeking vines, into the underbrush of briar roses, forsythia, and mock orange. So fertile and well-watered was Virginia Woolf’s imagination that some of the subordinate clauses sprout participle phrases that find their own route into the darkness under the overgrowth, without ever getting snipped from the main clause. Woolf nurtured her stories and essays along, like a gardener so obsessed with the beautiful particular details of a small plot of ground that she falls into an ecstasy or, if she’s lucky, a rapture.

“The petals were voluminous enough to be stirred by the summer breeze,” wrote Woolf in one excerpted passage on the wall of the Church Exhibition Gallery, “and when they moved, the red, blue, and yellow lights passed one over the other, staining an inch of the brown earth beneath with a spot of the most intricate color.” An example of finely observed writing that combines the detached delicacy of Japanese painting with the sensual decor of William Morris designs.

Woolf was in Bloomsbury before the rest of the famous group of writers and visual artists—T.S. Eliot, E.M. Forster, and John Maynard Keynes among them. She moved there with her siblings in her early 20s, after her mother and father had both died. Woolf and her Bloomsbury friends, thanks to the nihilistic effects of World War I on the sticky sweetness and soft-focus light of the Victorian era, were too pessimistic to believe anymore in a transcendence through the practice of the arts and the experience of nature. That Romantic urge for an opiate-induced oblivion belonged to the previous generation, and then again, later, to a certain generation born after World War II.

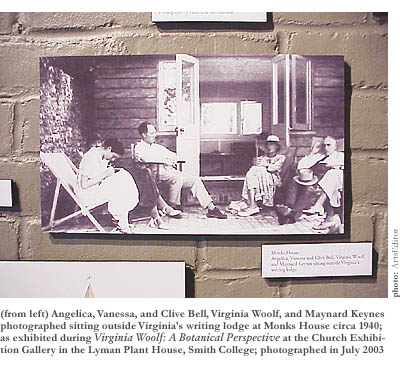

The abodes they lived in betrayed no such pessimism, however; and neither, really, in spite of her eventual suicide, did Woolf’s wonderful writing. Monks House in rural Sussex, where Virginia and Leonard Woolf lived after 1939, looks as solid and as softened by its atmosphere as a work of her fiction. A yellow-frame house, it’s surrounded by lots of walled, labyrinthine gardens full of potatoes, corn, berries, herbs, and leafy vegetables. There’s some outdoor statuary—maybe a few cement vases of flowers on brick terraces bordered by hydrangea bushes and pear trees. Dense groundcover crawls onto flagstones, reaching for light. And there’s the humble writing lodge where Woolf would sit with her back to the window for fear of being distracted from the cultivation of her writing. There’s even a photograph in the exhibit of Leonard Woolf working on his cactus plants in the greenhouse in 1966—an old man, long ago widowed by his groundbreaking wife, in vest and baggy pants, his tousled hair going well with his creased face, like a clump of unmown gray grass.

Nearby, an inconspicuous group of frames features a reprint from the January 2003 issue of Victoria magazine on this same country spread in Sussex. Though the article itself is interesting and well-written—Woolf is said to have claimed it was “bliss day after day” at Monks House, rather than rapture or ecstasy—Victoria appears to be the kind of magazine you fear will turn up on the bedside table of the too-cutesy bed-and-breakfast you made the mistake of making reservations at up near Woodstock or Manchester, Vermont. You know, in the same stack with back issues of Yankee, Country Living, and some Martha Stewart mag.

That about covers it—now you don’t have to go see it!—but it’s still worth experiencing for yourself, especially if you’d like to feel the electrical exchanges between and among Virginia Woolf, the English picturesque landscape style, Frederick Law Olmsted, and Smith College. Later, you can read To the Lighthouse again and notice how all the foliage curls around the pages of her prose. Or you can try The Hours, Michael Cunningham’s Pulitzer Prize-winning appropriation (or so they say) of Mrs. Dalloway, and then rent the movie (starring Nicole Kidman) to see if it all can work on your senses and get you back to the Garden.