It was neither dirt-cheap nor an opera but, hey, opera is for conservative, high-art snobs, and part of the $10 entrance fee was going to benefit the worthy Zeitgeist Gallery’s relocation fund. Besides, this was a rare chance for Bostonians to see a show by the critically acclaimed Bread and Puppet Theater, one of the oldest, nonprofit, self-supporting theater companies in the United States. Hence, the lines were long to get into their one-night-only performance of The Dirt Cheap Opera at the Cambridge YWCA last month.

Indeed, such was the level of turnout that the start of the show was delayed by a full quarter of an hour as the organizers plundered the building’s forgotten corners for more folding chairs. As they waited, the early-arrived initiates took the opportunity to browse the surprisingly puppet-free souvenir stand and stuff their Tibetan hemp-bags with anti-corporate, pro-creation (in the artistic sense) posters and cute, quirky booklets about the thoughts of squirrels. Others, more shy and less au fait with the Bread and Puppet ethic, stayed where they were and peered curiously at the makeshift stage consisting of a red curtain surrounded by a cardboard frame of roughly painted cherubs. We also have this delay to thank for the admission of one noted local arts aficionado that he was only there for the full frontal cardboard nudity he had read about in the promotional material. There was no obvious connection between this startling confession and the collapse of a table on which three latecomers were uncomfortably perched, but sometimes the flow of ideas in a paragraph obliges a writer to flirt with mysticism.

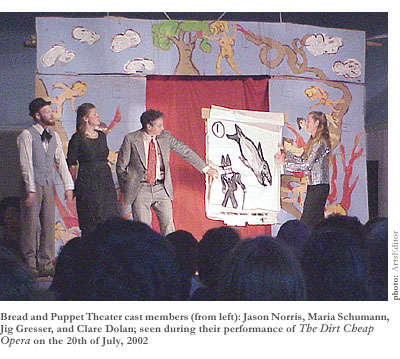

The play, loosely based on Bertolt Brecht’s Three Penny Opera, was a musical black comedy about a respectable young woman, Polly Peachum, who marries a dirty-collared Jack the Ripper clone called Mack the Knife—or, more familiarly, “Mackie”—with predictably unhappy consequences. Mackie’s history of theft, rape, and murder was established at the start of the play with the aid of a paper flip chart full of amusingly primitive drawings, narrated by members of the four-strong cast with suitably ironic gravity and hyperbole. Even a stabbed breast raises an absurdist (ahem) titter, although our favorite line in this sequence was the one about the Mackiesque shark with sharp teeth which—would you credit it?—he chooses to wear in his face!

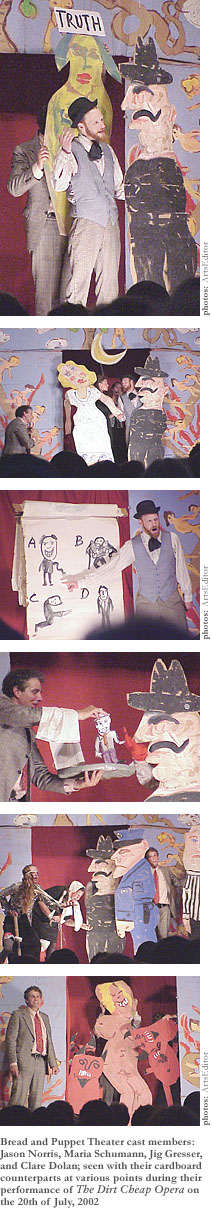

The flip chart was wheeled out at various subsequent points in the performance to introduce new characters and illustrate various random observations such as the victims of modern traffic (with their noodle arms), but its humor is overshadowed once the puppets themselves begin to appear from behind the red curtain. We say “puppets”, although “placards” would perhaps be more apt, not only because of their association with Sixties protest (in which era Bread and Puppets was born), but also because the large, home-made, cardboard images were, like placards, held up by broom handles taped to the back, rather than by hands or strings. Besides a couple of articulated arms and one scene in which a red glove was used to mimic the mouth with which the wicked Mackie eats his own brother, the puppets themselves were entirely static. Yet what they lacked in animation (and feet) they generally made up for in visual humor. Particular favorites of ours were Polly’s prim, outraged parents, the policeman who procrastinates as long as he can over arresting his fellow war veteran, Mackie, and, especially, the traditionally white-bearded God who repeatedly bellows “shut the fuck up” over the wailing of the miserable. Certain other members of the audience no doubt preferred the blond, buxom, naked prostitute (complete with train of red devils) whom Mackie visits soon after his marriage to Polly. Moreover, the scenes were far from short of visual dynamism, on account of the actors’ amusing habit of appearing from behind the puppets once their identification with them had been established in the audience’s mind, to address and interact with each other directly.

We were grateful to be spared any attempt at cockney accents, despite the play’s setting in Eighteenth Century London. Nevertheless, the vocal element still managed to rather let the play down. True, there were no hiding places for any tonally challenged cast members amidst the songs’ stark instrumentation of a few drums and an accordion, but the fact remains that most of the numerous songs in this “opera” (Maria Schumann’s excepted) were distinctly trying on the ear. No doubt the puppeteers would argue that the flat, shrill notes were as much part of the fun as the childish drawings, but surely there is a limit to the amount of humor that can be wrung from such sonic barbarity. Anyone with a remotely sensitive ear could have told them that humor in songs is best confined to the lyrics. And there was humor in that department; particularly memorable for us was Polly’s world-weary confession that she had married Mackie because he was the only man who hadn’t tried to attract her. The same character—though different cast members—subsequently sang about Mackie’s walking all over her (illustrated with gleeful if predictable literalness) before taking up a bottle of whisky when he left her and listening as the goddess of Love attempted to comfort her. The terms of consolation were typically banal before the goddess suddenly brought her song to an abrupt halt with the declaration that everyone could see all along that Mackie was a no-good bastard and that there were plenty more fish (shouldn’t that have been sharks?) in the sea for Polly to choose from.

We were grateful to be spared any attempt at cockney accents, despite the play’s setting in Eighteenth Century London. Nevertheless, the vocal element still managed to rather let the play down. True, there were no hiding places for any tonally challenged cast members amidst the songs’ stark instrumentation of a few drums and an accordion, but the fact remains that most of the numerous songs in this “opera” (Maria Schumann’s excepted) were distinctly trying on the ear. No doubt the puppeteers would argue that the flat, shrill notes were as much part of the fun as the childish drawings, but surely there is a limit to the amount of humor that can be wrung from such sonic barbarity. Anyone with a remotely sensitive ear could have told them that humor in songs is best confined to the lyrics. And there was humor in that department; particularly memorable for us was Polly’s world-weary confession that she had married Mackie because he was the only man who hadn’t tried to attract her. The same character—though different cast members—subsequently sang about Mackie’s walking all over her (illustrated with gleeful if predictable literalness) before taking up a bottle of whisky when he left her and listening as the goddess of Love attempted to comfort her. The terms of consolation were typically banal before the goddess suddenly brought her song to an abrupt halt with the declaration that everyone could see all along that Mackie was a no-good bastard and that there were plenty more fish (shouldn’t that have been sharks?) in the sea for Polly to choose from.

Other gods who made their appearance in the play were Truth, Money, Justice, and his twin brother, Revenge. Their presence was evidently intended to give the proceeding the air of a surreal morality play—to, as the promotional material put it, “make sure that the dramatic events are put into the right light and judged instantaneously and by the proper authorities.” Hence, the narrative raised its placards (figuratively this time) towards the end of the proceedings and suggested that even the serial felon Mack the Knife was really just a victim of his noble refusal to sell his soul to nine-to-five capitalism. “What is the rape and murder of a human being,” we are asked, “compared to the crushing of an individual’s spirit? What is the robbing of a bank compared to the founding of a bank?” Of course these lines were delivered with tongues firmly implanted in cheeks, but their passing resemblance to Bread and Puppets’ above-mentioned liberal-artistic philosophy was surely no coincidence—and the nods of semi-approval were unmistakable from the hemp-bag brigade. Mackie is spared the hanging he receives at the end of the play’s Brechtian parent not only because the tiny noose does not fit over his inflexible cardboard hat, but also at the merciful dictate of the god of Justice. The castle and directorship of Chase Manhattan bank he also receives as part of his pardon shone an arc light on the point for anyone who missed it, and one can only wonder how he managed to avoid being appointed to the board of Enron or WorldCom whilst the god was at it.

In the end, despite all the above-mentioned highlights, we left the scene of the crimes feeling rather disappointed—not only because ArtsEditor‘s format obliged us to discard our original title for this piece—”Naked Puppets on the Rampage”—but also because the show hadn’t really lived up to it anyway. We concluded that the laughs just hadn’t come often or boisterously enough to really carry the grating singing and the school-play production. Indeed, there had been times when we were rather embarrassed for the cast as they labored through whole songs without a laugh-worthy line. We wished they had been more inclined to stay behind their puppets, if not to muffle their voices then to at least hide the shame they must have felt on one or two occasions for not having done so.

Still, it is summer, the silly season, and the time when one’s tolerance for the antics of shameless fringe-festival types is at its height. Certainly the audience’s patience was in abundance, as their enthusiastic applause at the end of the performance attested. Indeed, some of them apparently returned for a second viewing later in the evening (to, as one of the cast members wryly put it, catch all the intricate plot details they had missed the first time round). After all, regardless of its quality, there is nothing like the warm feeling of having experienced real logo-free, grassroots folk art in these times of rampant corporate iniquity—right? And personally we have both always thought that our brothers would be distinctly tasty if served with a nice tapenade.