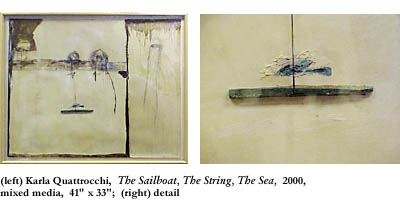

I can detect a few clues, but only a few, that the paintings and mixed-media pieces on display in the plaza-level gallery at Boston’s City Hall were made by Charlestown residents. These clues do not include Thom Carter’s green, yellow, and purple mountain-and-river landscape, Ode to Claude, a fairly florid picture which looks more like a view of the southern White Mountains from the banks of the Pemigewasset River north of Concord, New Hampshire, than it does a view of Bunker Hill from the paved banks of the Mystic. They don’t include Anthony Abate’s placid lakescape, Woodland 6, a by-turns kitschy and just-plain-pretty nature painting most admirable for its rendering of slender birches and the cool, inviting perspective from the headwaters of a lake. Nor, on the edgier and more urbane side, do they include Karla Quattrocchi’s evocative and spare mixed-media abstractions, The Sailboat, The String, The Sea and House with Patio, both large and exhilaratingly elusive pieces dominated by smokey gold and black on what looks to be handmade paper. No, and not Donald Kelley’s Lips either, a funky three-dimensional wall-hung construction featuring, from top to bottom, several horizontal strata of deeply colorful paper strips, like a flattened section of rainbow gone at with a pastry knife.

For the seeker of regional imagery, there are plenty of clues that this is a show of works by the Artists Group of Charlestown. Jim Heskett’s whimsical, minimalist, crayon drawing of the now-defunct Schrafft’s candy factory that can be seen at the far northern slope of the long ridge that is Charlestown from the speedy lanes of Rt. 93 in the East Cambridge/Somerville area, for example—a piece done fittingly in candy colors. Lori Warner’s broad-stroked, foreshortened, and tilted view of red-brick townhouses arranged Around the Square (Monument Square, presumably) on the edge of a shady green slope, cleverly offering a soft blue path to take all the way from the bottom of the frame to that spot, more than halfway up, where suddenly a bend disappears around the knoll to the left. Or Joe Caruso’s Trinity Church—oh, that’s in Copley Square, isn’t it, not in Charlestown?—a large woodcut worth an admiring look for its symmetrical structuring of black marks on white vertical space, and for its bold renderings of roof tiles, decorative embellishments, and darkened archways and windows, an ode to H.H. Richardson’s creamy brown masterpiece that corroborates the working definition of architecture as frozen music.

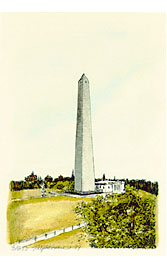

No, Trinity Church is not in Charlestown, but the Bunker Hill Monument is, and Joe Trepiccione has drafted a quiet and concise watercolor print of that tapered granite homage to that peak stop on the Freedom Trail. Titled The Lodge (for the white colonial manse that squats at the base of the monument, I guess—a manse that isn’t still there, is it?), it could make the artist some money for supplies if reproduced on a postcard rack in gift shops across the city. A faint, diagonal blue streak against the white sky intersects the vertical icon with a subtle brush-stroke; browned grass at the base of the obelisk might mean it’s fall or early spring, not currently tourist season; one of the two visible planes of the tapered monument is in shadow—evidence of the simple satisfactions to be had in observing someone else’s accurate observations.

That’s about it for the regional renderings; it isn’t local-color art for the most part that the motley members of the Artists Group of Charlestown are doing. Most of the members are from elsewhere, with aesthetic concerns that cross the town limits. No other works here refer to other parts of Charlestown’s history. There are no potential postcard etchings of the Warren Tavern, for example, where Paul Revere practiced holding his liquor (in his hand-forged flagon, maybe) and ordered lobster that was far cheaper than chicken back then. No U.S.S. Constitution tied up at the dock, with the Naval Yard or the steeple of the Old North Church in the background. No Mystic River bleacher-view photograph across the Charlestown High football field, where a black kid was shot from a nearby roof and paralyzed for life by a white kid some 20 years ago, when the mid-’70s busing crisis had already become a national legend and tarnished Charlestown’s reputation for good, in spite of late journalist Anthony Lukas’s sympathetic portrait of a representative Charlestown family in Common Ground, the docu-epic that also features sympathetic portraits of Roxbury and South End families. And no garish, expressionist view of the 99 Restaurant near Bunker Hill Community College—surrealistically juxtaposed to the colonial graveyard full of gloomy gray headstones next door—where the four smalltime mobsters were blown away by some pitiful rivals over their legendary steak-tip dinners about a decade ago.

Larry Bowling’s not concerned with the sense of place in his untitled mixed-media collage-like works. (The one juxtaposing borrowed images of blue-flowered hyacinths, a man with folded hands, a postmarked envelope, and an old pocketwatch on metal plates, with a green, burnished-copper underlayer is especially gorgeous: polished, precise, and at least mildly suggestive, conducting some of the psychic electricity of a similarly pop-art piece by Robert Rauschenberg.) Rob Dinsmore’s photorealist painting, Fourth Floor, Charlestown House, ‘local’ only in its title, is polished, clean, and professional (maybe a bit too so) to suit the lifestyle suggested in its depiction of a spacious attic interior replete with open doors, old bathtub, banister, oriental rugs, and skylights admitting abundant light.

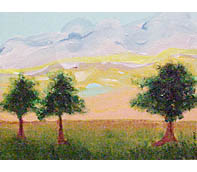

I keep going back to these works. I stop along the way for appreciative inspections of Dara Pannebaker’s small and bold Tree Series (dark-green bushy trees in a foreground field against a rippling mountainscape) and Jim Latina’s swift, distinctive, brush-action-packed Hacienda paintings (one of them Obscured, the other Emerging). And I keep going back to Karla Quattrocchi’s too, wondering if she had as much fun suggesting, just suggesting, the fishing scene in The Sailboat, The String, The Sea, with her mixed media of mesh and resin, pencil and paint, as I do inferring the setting from the scant imagery.

Yes, back and forth I go, pacing the room leisurely, gathering it all in, happy that City Hall is showing off the accomplishments of local artists, embarrassed by my habituation of Newbury Street’s glitzy galleries, and reminded that for every Monet and Manet there are several dozen people following in the footsteps of the pathmaking pioneers of the art world, who get an aesthetic rush, a peak poetic experience, perhaps a profound sense of connection and comprehension, in their hard-earned free time, out of the same endeavor that the trailblazing Robert Rauschenbergs, Louise Bourgeoises, and David Hockneys of the world are lucky to be famous for. When I pass by the rainbow strata of Lips for the fourth or fifth time on my way out the door, I have no idea that in the next week I will see, from the Mass. Ave. bridge, two parallel rainbows, better than any sterile abstraction from a Ellsworth Kelly or Morris Louis painting, with the northern ends of its yellow, orange, red, and violet beams rooted in the approximate vicinity of Charlestown—or close enough anyway to make me wonder if the earnest and eclectic members of the Artists Group of Charlestown, exalted in their bright studios by the experience of being inside a prism, had stepped down to the street to dip their brushes in the pots of gold.