You can’t miss it. It’s right there in the alcove near the washrooms and the café—flanking the curtained R-rated section of the exhibition. In this “process” gallery, supplementing Pretty Sweet: The Sentimental Image in Contemporary Art, on view through April 17th at the DeCordova Museum and Sculpture Park, is an instructive exhibit that gives the curious and studious among us a peek behind the scenes in the studios of the artists. Of the 33 artists in the exhibit (many of them Boston-area artists), five or six have contributed documents of their work habits and materials—videos, photos, captions, notebooks, and the like.

In one no-nonsense video, we can watch one artist, Amy Podmore, busily disemboweling dolls, turning them inside-out, and casting them in plaster for the airborne collection that hangs by wire from the ceiling in the Window Gallery on the second floor. We can look at snapshots of the Islesboro, Maine, summer shack where Candace Walters and Brenda Atwood Pinardi collected an explosive variety of kitschy crucifixes, rosy-cheeked dolls, natural relics (antlers, shells, and branches), and assorted pop-culture paraphernalia for enshrinement in an actual replica of the cabin that we can walk into and everything. And at one other station, we can pick up postcard reproductions of the dazzling and colorful artworks from the exhibit and move the hands of a huge dial to one or another combination of adjectives arranged where the dash marks on a clock would be. It’s a magic mood-o-meter, a tongue-in-cheek crack on the rationalistic emphasis on quantification, and it invites us to articulate our complex, ambiguous reactions to the works. Amused, sad, and nostalgic—we can be all of these at once! Angry, aroused, and elated? Why not?

The mood-o-meter serves as a light-hearted, youth-oriented complement to the astute, art-historical remarks of Nick Capasso and Alexandra Novina in the exhibition catalogue. In their essays, noting the fascination of current artists with found objects, refuse, and the recycled mass-production of things and ideas, they classify the contemporary uses of the sentimental image—an image that, from centuries of use and abuse, has become a hindrance to authenticity. Like theologians with quiddities, the curators cite three common uses: the often didactic social critique of the feminist artist who’s working in the wake of Judy Chicago; the ambivalent half-celebration, half-denigration of the campy Pop artist who’s learned the ropes from Andy Warhol; and the helplessly romantic indulgences of the sacred-object artist who’s still reading Rilke and weeping at Rodin and turning the pages of coffee-table books on Matisse and Cassat. For fear of overestimating the importance of their classifications, they remind us, though, that the artworks sometimes overlap. That iconic flower, kitten, doll, heart, or warm ‘n’ fuzzy teddy bear could be exploited for feminist, camp, and romantic purposes all at once.

Usually, it’s pretty easy to tell, in this visually delicious exhibition, which of the holy trinity of uses the artist inclines toward most. Being didactic and somewhat obvious (and verging, at times, on the cliché), the conspicuous feminists are a cinch to spot. Ilona Anderson, up there in the adults-only section, has that heart-shaped arrangement of tissue boxes on the wall—each one covered with the sort of sugar-sweet cloth doily that a broken-hearted teenaged girl would have next to the pink princess phone on her nightstand. On closer examination, we notice that the slit in each vertically mounted box, from which the tissues can be drawn as the tears start to flow, is, well, vaginal. Each one bears at the top of the vertical slit a tuft of wool fuzz in one or another pubic color, after all. Anderson unmasks the sanitized and prettified commercialization of American female adolescence to reveal the hidden symbol of the Kleenex box, giving us a sympathetic feeling for the weeping girl and her suppressed animal nature, as it were.

We’ve already heard about Amy Podmore and what she does to dolls and stuffed animals. Same idea there—no sugar, plenty of spice, plenty of plaster, and nothing very nice, all in understandably angry denial of the dainty roles that certain male-dominated cultures may still assign to women. Kathleen Bitetti, too, comes from the old school of rebels, as evidenced by the entirely whitewashed installation that greets us near the entrance to the museum: whitewashed tree stump with whitewashed cradle-like birdhouse full of nails and whitewashed ceramic cardinals on window ledges up and down the stairway to heaven from the lobby, with—yes—whitewashed recording of “Rockabye Baby” tinkling from the wall. Nearby, in the lobby, Katherine Desjardins has painted a corny but cute flower in the window and drawn a huge collage of ’50s-era coloring-book creatures—kids and barnyard animals and all—on the wall above the front desk. Sort of a spoof on the same expectations of women to be mothers and nothing more. And sort of “feminist”—or is it?

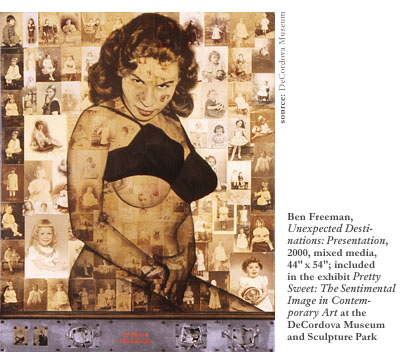

Maybe Desjardins belongs in the second category—in the Warhol camp. That’s the kind that shows us how cloying commercial imagery finds its forceful way into our suddenly less refined art lives no matter what we say to criticize it and before we can put the high-minded thought-police on patrol to stop it. And maybe, come to think of it, Bitetti belongs in that category, too. But someone in this exhibit besides Ilona Anderson and her tissue boxes surely must inhabit the feminist category alone. And leave it to one of the guys to pull it off with surprising freshness. Ben Freeman’s three big prints, in sepia tones, juxtapose images of objectified, ’50s-era pin-up girls (we can’t call them pin-up “women,” can we?) with headshots of plain young schoolgirls with nothing lurid on their minds and better things to look forward to than careers as sex kittens. Strictly a commentary on perverse social conditioning, this series can’t be placed in the second or third category. It makes its point profoundly well.

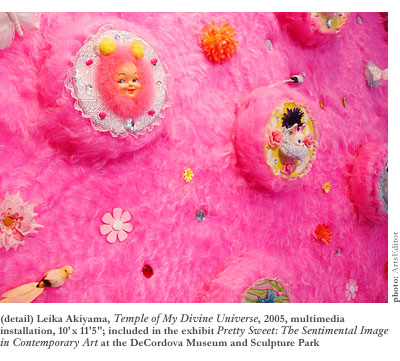

There’s no doubt that Leika Akiyama, with massive, symmetrical, shrine-like collages of gaudy dolls, fake feathers, Valentine hearts, and paper butterflies, has at least one foot in the Warhol camp. She embraces and rebuffs concurrently this Hallmark-heavy cultural paraphernalia. And her work’s large presence on the third floor is fine, but the prevalence of dolls in the exhibit tends to make the icon seem like an easy target. (Less is not necessarily more—but more can be a lot less.) On the gentler, technically impressive side, Lorie Hamermesh’s two life-size images of nude goddesses explore the sometimes sentimental image of the female body (object of holy and unholy adoration and source of all human life) in a calmer, less hysterical, and quietly amusing way, their discrete layers of silk, acetate, and paper working together to form from a distance a unified image that from a side view appears as three separate pieces. She’s tweaking the pre-Raphaelite idealism of femininity for sure—but the skill and craft that go into making the luminous images keeps the message from being strident, and there’s no sticky-sweet sentiment either.

We wouldn’t put Robert Arnold in the third category—diehard romantic with a sincere love of innocent beauty—with his hilarious, practically miraculous video loop, The Morphology of Desire, of multiple, stereotypical, romance-novel couples morphing seamlessly from one received lifestyle in one cliché-ridden setting to another—would we? Nah. We’d put him in the second camp too, and then we’d go back to watching the couple in the groovy bachelor pad lose their martinis and pivot gracefully into their new incarnation as a couple all bundled up on the ski slopes and then into a couple of ripe suburban sensualists on the backyard patio—each time appareled in the garments of the given stereotype and all the time full of beautiful teeth and square jaws and narrow waists and lovely rumps.

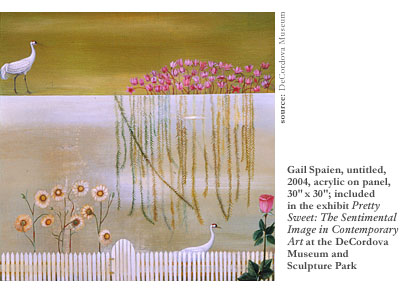

But we would count Ann Wessmann a member of the third group, looking at her absolutely precious Family Hair Series, each framed arrangement of braids or globes of hair mixing gold and gray, young and old, girl and woman, with exquisite and affectionate precision. We would say she’s got tenderness toward existence. And we would say that about Wessmann’s neighbor in the exhibit, too—Gail Spaien—whose antique-motif post-mod samplers of flowers, birds, and water-, land-, and skyscapes bring us back dreamily to the lavender-scented version of the 19th Century that we can still smell in New England.

And we would say that, too—”You bet he’s got tenderness toward existence all right!”—of a man named David Prifti, who emulsifies old family photos onto beat-up, rustic sections of wood paneling and rusted metal. Especially we would say that while looking at the one called Flight—featuring a slender, 20ish, early-20th Century fellow in his Sunday best stepping our way with a released look on his face, a crowd of young and old well-wishers behind him in support, as if seeing him off into his new adventures in adulthood, the freedom-loving silhouette of a bird in the sky above him serving as guide and model. An appropriation of an ordinary-seeming family photo that, arranged on a jagged piece of metal, gives more symbolic weight and emotional resonance to the photo than it probably had in its original form on the tintype. It’s enough to break the heart of someone who’s not even related to him, and, as Robert Frost wrote by some abandoned cellar holes in the hills, enough to make you “weep for the little things that made them glad.”

Even as we recall these and other wonderful works from Pretty Sweet: The Sentimental Image in Contemporary Art, we feel the many hands of the mood-o-meter within turning clock- and counter-clockwise, wildly or not, in search of the adjectives that can approximate our pleasure.