The Southwest connotes in the mind the ideal American landscape—limitless, unspoiled, and serene. As modern life becomes increasingly chaotic and congested due to technology and overpopulation, the idyllic American frontier becomes an oasis. Like our pioneering forefathers, discontent with the sprawling East, our notion of landscape beauty moved past the Mississippi long ago.

In celebrating this heritage, the Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover compiled three films into a series entitled Moving Pictures: The American Land. The film series was a supplement to two winter exhibitions of landscape work at the Addison—Reinventing the West, which featured the work of landscape photographers Ansel Adams and Robert Adams, and The American Land, which included selections of painting, photography, and drawing from the Museum’s permanent collection spanning 125 years.

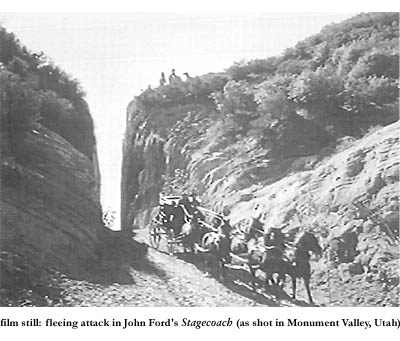

The series began with Stagecoach (1939), the pioneering western directed by John Ford that became the archetype for all other Hollywood westerns to follow. Shot in Monument Valley near southern Utah, Stagecoach was groundbreaking in its use of wide-angle camera lenses and natural scenery to revitalize the slumping western genre.

It is also the film that made John Wayne a movie star. Ford gambled on Wayne as an actor, lifting him out of B-movie obscurity. The famous close-up scene where Wayne’s Ringo Kid is first seen waving a Winchester rifle confirms the legendary status of both the picture and the star.

Set in a frontier town, a band of quirky characters assemble and travel by stagecoach to the town of Lordsburg, while attempting to outrun the Indian rebel Geronimo. Each character has his or her own reason for escaping to Lordsburg. Claire Trevor plays Dallas, a prostitute, who finds herself ostracized by a self-righteous community. She falls in love with The Ringo Kid, who is out to settle a score with an old enemy. Joining them is a haphazard collection of characters encompassing the broad spectrum of sociological class: a doctor, a banker, a whiskey drummer, a soldier’s wife, a gambler, and the two working-class stagecoach drivers.

The cast is a collection of memorable American actors from the 1930s and 40s. Thomas Mitchell (High Noon) plays Doc Boone, a drunken but surprisingly competent practitioner. John Carradine (The Ten Commandments, House of Frankenstein) plays the savvy gambler. Donald Meek plays the unassuming whiskey drummer, and Berton Churchill plays the stodgy old banker.

Ford’s visuals and creativity still inspire awe. His ability to carry on a chaotic chase scene against the grace of Monument Valley’s heavenly landscape is a testament to his filmmaking greatness. Giant sandstone buttes and granite rock formations spring from the endless valley plain while the narrative moves effortlessly from scene to scene. Each character is a joy to watch.

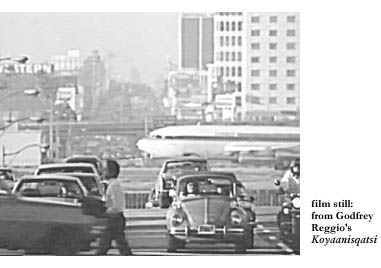

The beauty of the vast, breathtaking frontier is easily apparent when contrasted with scenes of urban congestion. No greater example of this fact is seen than in Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi (1983), the second film of the series.

This experimental, groundbreaking work pairs two worlds in unequal juxtaposition. One is the undisturbed, scenic, natural environment; the other, a frenetic, human-engineered Koyaanisqatsi, a Hopi Indian term for “life out of balance.” The Arizona and Utah valley corridors hold most of the meditative center for unspoiled, natural scenery, but not for long. Scenes of peaceful wonder are quickly replaced with chaos, as New York City is chosen as the backdrop for a spiraling, human-infested blight upon Earth.

The intense visuals and underlying message of Koyaanisqatsi remain as potent today as the film’s release nearly 18 years ago. From aerial shots of the Grand Canyon to dizzying clips of Manhattan bustle, Reggio’s film reminds us that our rocket-fueled culture, set on overdrive long ago, will burn itself out at its current clip. Horrific visuals of polluted oil fields, nuclear test sites, and miles of military weaponry serve as not-so-subtle reminders of humanity’s steady path towards self-annihilation.

In addition, poverty, environmental pollution, overpopulation, automated assembly lines, soulless consumerism, (again, mostly occurring in New York), escalate in the film to suffocating proportions, leaving the viewer with an overwhelming sense of humility. Koyaanisqatsi is effective in holding up the mirror to the inherent madness that the excessive technologies and economies of Western civilization have wrought.

Yet in all fairness to Western civilization, it is easier to portray the inherent madness of any society when the director consistently speeds up the camera. A frantic time-lapse technique is employed quite frequently throughout the film, creating the effect that things are happening at an absurd rate of speed. It is a technical merit, on the one hand, that has spawned countless imitations, particularly among amateurs; but a groundbreaking technical achievement sometimes detracts from a film’s timelessness, which I think is the case here.

Two aspects pertaining to the film’s soundtrack are clearly dated. The music of Philip Glass increasingly grates on the nerves with its continuous barrage of obsolete keyboards and moog sounds. Also, the random chanting of the word “Koyaanisqatsi” does not sound as sacred and apocryphal as once intended.

James Benning’s El Valley Centro picks up where Koyaanisqatsi left off, juxtaposing the serenity of the natural world with the obstreperousness of the man-made. Less heavy-handed and more evenly paced, Benning’s film was a 2000 Sundance film festival winner. Intended to be a microcosm of the larger social problems it touches upon, El Valley Centro focuses on an underpopulated rural region of southern California. Farming communities, construction sites, suburban backroads, and outlying desert valleys combine to paint a complex portrait surrounding this region.

The film moves slowly, comprised of two-and-a-half-minute shots, each meditating on a particular aspect of the valley. A sprinkler system hovers in the foreground of enormous farming acreage. A commercial train line rolls on endlessly, as each caboose is seen empty and deserted. A chemical is fueling an explosion, spitting black fumes into the ozone.

Some shots intend to spark outrage. Others are deceptively serene. Most of the scenes have the common thread of a man-made interference, even if it is merely nearby traffic noise overheard in a peaceful orchard valley.

Benning shows remarkable skill in filming some of the farming scenes. In one instance, the camera is placed firmly in the center of the shot of a rural landscape. The engine noise of some distant farming machinery is heard through a foggy atmosphere of an early morning. The engine noise grows increasingly louder until the lights of a soil tractor are seen approaching the camera. Just before it looks as if it will come too close for comfort, the tractor makes its turn to plow the other end of the field.

The three films, Stagecoach, Koyaanisqatsi, and El Valley Centro, are markedly different from each other in age, style, and content. Underlying these differences, however, is the revelation of a deep-rooted respect and reverence for the land in capturing the majesty of the Southwestern landscape, and at the same time, accurately portraying the finiteness and smallness of human affairs against this backdrop.

This month, The Addison Gallery of American Art is screening three more films in a series titled Moving Pictures: Poetry and Film, which documents the roots of poetry performance and the poetry slam since the early 1980s.