“The visionary starts with a clean sheet of paper and reimagines the world.” —Malcolm Gladwell

No characteristic distinguishes man as decidedly as our desire for memory and meaning. Since the very beginning of time—from the mysterious and otherworldly scenes painted on the walls of the Lascaux caves over 17,000 years ago, to the cuneiform script that emerged in Sumer during the late 4th millennium B.C.E.—man has sought out ways to transmit ideas from one generation to the next. But perhaps no issue plagued our early ancestors as much as this: on what material could they transcribe their ideas and images to make the information simultaneously durable, portable and meaningful?

Enter paper, and its closely related predecessors papyrus and other varieties of tapa, which had the benefits of being light and pliable—they could be easily rolled, folded or bound into books—and, if properly protected from excess damp or fire, exceedingly stable. The first development of paper as we know it can be traced to China, where, at the beginning of the first century A.D., a man named T’sai Lun is credited with creating the “modern” papermaking process, which remained largely unchanged until the industrial revolution. Prior to the digital transformation at the beginning of the twenty-first century, no material had done more for the retention and transmission of knowledge and beauty than humble paper. But is it still relevant? Does paper still have a role to play in the creation and preservation of humanity’s aspirations?

Although Art on Paper, a newcomer to New York’s Armory Arts Week, did not set out to answer any of these questions, these are precisely the issues I found myself pondering as I wandered through this engaging fair. Art on Paper is the brainchild of Art Market Productions, a Brooklyn-based company that has been bringing its unique blend of high-quality, cutting-edge exhibitors and hip and accessible presentations to fairs including Art Market San Francisco, Market Art + Design, Seattle Art Fair, Texas Contemporary and Miami Project since 2011. Working with the Brooklyn Museum and cultural partners that included ArtTable, El Museo del Barrio and the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, among others, and presenting sponsor, The Wall Street Journal, Art on Paper delivered a refreshing program that showcased the diversity of forms, applications and manipulations open to artists working with paper today.

As any visitor to the main Armory Show—or, for that matter, many of its increasing number of satellite fairs—knows, galleries participate in these events in order to woo collectors and make sales. This inevitably results in booths stocked with vibrantly colored oils, shiny, large-scale metallic or stone sculptures and a marked bias towards figurative art and abstractions that have already been varnished by history. Although none of these propensities is a problem in itself, together they tend towards a homogenous presentation of artistic practice. These fairs can be a visual assault: the loud colors and monumental scale of most of the works overwhelm the visitor and drown out other media that cannot be appreciated from a distance in a single glance.

Located on the Lower East Side of Manhattan at Pier 36, Art on Paper (March 5-8) was connected to the majority of Armory Arts Week events, which orbit around Piers 94 and 92 on the West Side, by free shuttle buses that departed every ten minutes. This distance helped to increase the impact of the fair: if the Armory Show is best characterized by its riotous color and vast scale, Art on Paper is distinguished by its whimsical, delicate and intimately-sized works. Far from only including drawings, prints and watercolors—although there were numerous representations of each of these traditional paper media—Art on Paper demonstrated the range and adaptability of paper to twenty-first century ideas, with its 55 galleries presenting everything from giant, movable puppet-sculptures of confederate soldiers to vivid abstract oils to mixed media collages and everything in between.

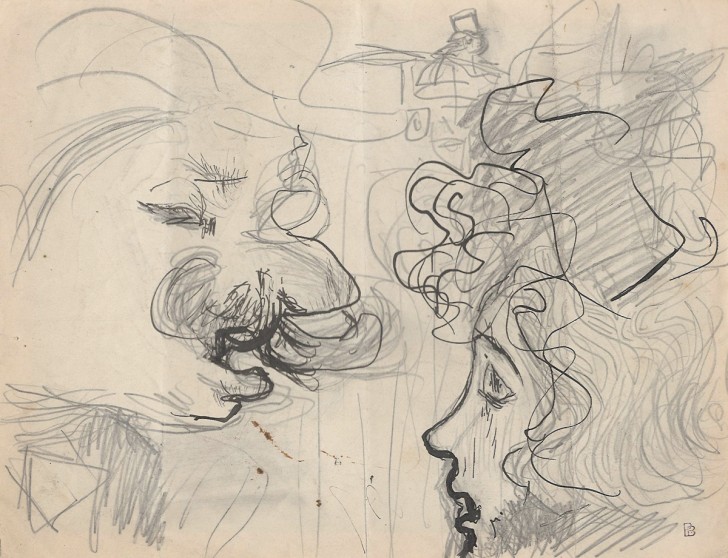

Although contemporary art took center stage here, as it does throughout the Armory Arts Week fairs, there were examples of artworks on paper by renowned ninetieth and twentieth century artists that did much to establish the historical context of the more recent works. Jill Newhouse Gallery, for example, had a lovely selection of small-scale sketches, pastels and master drawings by such distinguished names as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Charles-François Daubigny, Edgar Degas, Édouard Vuillard, Pierre Bonnard and Gustav Klimt. As a student of art history, I have always been fascinated by artist’s sketches, for it is in these works that we see the artist searching for answers to compositional questions; they are the artistic equivalent to a writer’s diary. This booth also incorporated contemporary works on paper, and seeing the older, seemingly instantaneous sketches alongside the polished, made-to-be-purchased contemporary pieces provided one of the most thought-provoking juxtapositions of the fair.

Still other galleries brought examples of enshrined Post-War masters like Willem de Kooning (Forum Gallery) and Robert Rauschenberg (Nancy Hoffman Gallery) or prominent contemporary artists like John Baldessari, whose National City, a series of eight photographs of his hometown with hand-painted acrylic circles, was a powerful presence on Richard Levy’s booth. Yet, although I appreciated the presence of these canonical pieces, it was the diversity of form and rich exploration of contradiction and meaning evident in many of the more recent works that held my attention throughout my visit to the fair.

Among the most delicate artworks to be found were two hand-cut sheets of white paper by Jaq Belcher at JHB Gallery’s booth. Mounted within their own white-framed shadow boxes, the works were created in 2015, making them also among the most contemporary of the contemporary works on display. Each sheet had been carefully traced in faint graphite pencil with organic, petal-like forms that the artist had then gone back over with a blade, cutting them on three sides and slightly bending each one to create a raised pattern over the surface of the sheet. No color was applied, and yet, as light moved across the shapes, it created the most incredible patterns of light and shadow, animating the surface and producing different impressions depending on the angle and perspective of the viewer. That these monochrome, all white works were able to arrest the attention of fair-goers is justification enough for the Art on Paper concept: the context and scale of this fair was capable of illuminating the understated beauty of these artworks and others like them.

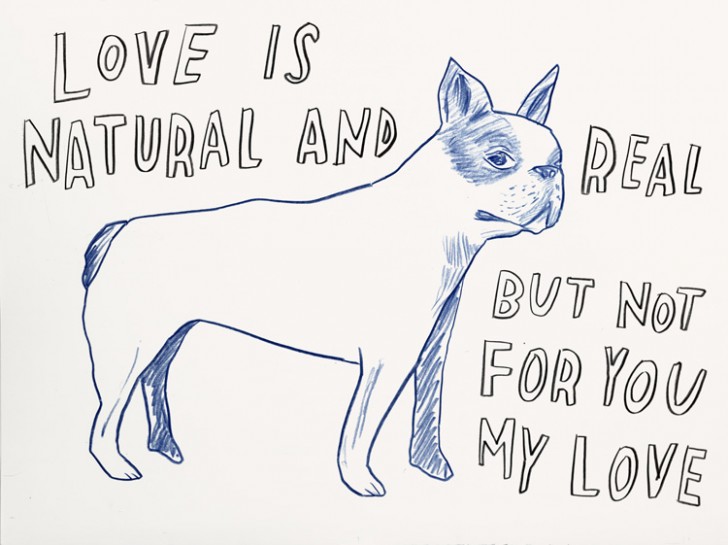

At least one gallery displayed the work of an artist/author, whose relationship to paper is doubly ingrained in the creation and transmission of ideas and emotions. The visitor, on first entering the fair, was confronted by a monumental reproduction of a drawing of a rabbit emblazoned with the word “glory.” The work of Dave Eggers, the noted author of the memoir A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius and founder of McSweeney’s, the drawing itself could be found on the booth of San Francisco gallery Electric Works, which devoted its entire program to Eggers’ recent animal/text drawings. In the drawings, which are at once realistic and humorous, various animals seem to stare outward and engage directly with the viewer. But it is in the choice of text—sometimes a single word, sometimes a quotation from the Bible, sometimes a humorous aside or pointed observation—that Eggers gestures towards a tension between image and language, vision and meaning and seeks to elevate the drawings to the realm of his prose.

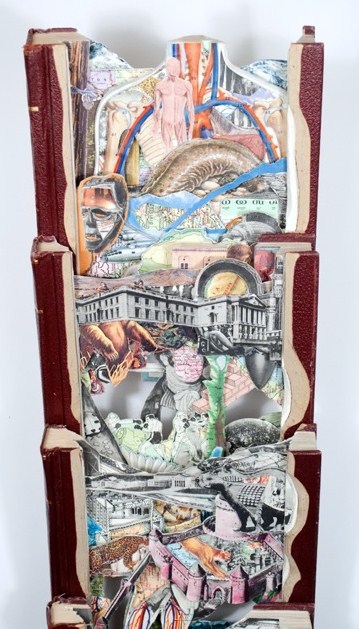

In a fair devoted to paper, it was also rewarding to see how many galleries chose to display works by artists using books as their inspiration. Although many different examples warrant mention, including Phil Shaw’s witty bookshelf prints at Rebecca Hossack, two examples stand out for their ecstatic view of books’ role in the communication and transformation of knowledge. Also at JHB Gallery, a selection of Brian Dettmer’s book sculptures captured my imagination in a powerful way. In New Standards, for example, Dettmer takes a set of Standard Encyclopedias—relics from the pre-Google, pre-Wikipedia universe—and cuts through their covers and pages to create a collage of layered images representing the information contained within. Thus, volume “A” contains images of anatomy, while “D” contains a three-dimensional world of roaming dinosaurs, and “M” presents the viewer with Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam. In addition to calling to mind the old adage, “a picture is worth a thousand words,” New Standards left me with the impression of knowledge that can barely be contained, of ideas bursting forth in a glorious profusion, literally breaking through their bindings in order to engage with the wider world.

Even more evocative was RandallScott Projects’ presentation of Meg Hitchcock’s text drawings that use letters painstakingly cut from the world’s holy books to recreate passages from other religions. In one particularly powerful work on display, Hitchcock took letters from the Koran and refashioned them into a passage from the Hindu Mundaka Upanishad, forming a delicate, overlapping multi-strand loop—not dissimilar to a string of pearls—on their paper mount. Hitchcock’s works seem to simultaneously question and rejoice in humanity’s quest for spiritual enlightenment. Her deconstruction of the most sacred texts ever to be bound into worldly books leads to interesting questions about the fallacy of truth and the various ways knowledge can be manipulated and reinterpreted.

As with all fairs, Art on Paper was not without its moments of kitsch. A few too many galleries chose to bring photographs of Andy Warhol—that pinnacle of the blue-chip artist. Although a common enough site at the larger art fairs, these images stood out in a more pronounced way at Art on Paper. In an environment marked by its tendency towards introspection and ideas, these photographs were manifest reminders of the commodification and celebritization of contemporary art, and the million dollar price tags accompanying many of the works on display at the Armory Show. But in its exploration of the ways paper has served as the conduit of ideas, memory and meaning for thousands of years, Art on Paper highlighted the intrinsic value of a medium that has, in countless ways, allowed us to “reimagine the world.”