The day was bright and the streets were noisy, crowded, and bustling. My able associate had earlier informed me that I needn’t worry about finding our way through this section of Boston as she had a familial familiarity with it. Nevertheless, after four rights and just as many lefts, I reached the conclusion that, while I trust and respect her immensely, the map in the book really ought to be consulted.

Not that this was any ordinary map book. Nor were we seeking any precisely ordinary landmark. We were looking, in fact, for the Chinatown Heritage Mural, and the book we were carrying with us was Walls That Speak: a Guide to Boston’s Outdoor Painted Murals, the pet project of recent Emerson College publishing graduate Katie Hazard.

Walls That Speak is a combination of coffee table book, social history, and tour guide of many of the narrative murals in the greater Boston area. It started life as a student project but it wasn’t long before it occurred to Hazard that it could make a real book. Her argument is that there exists in Boston a sufficiently large group of people interested in community arts with enough time and curiosity to value a book of this nature. Moreover, there is also a sufficient level of gentrification taking place within the described neighborhoods to allow them to visit the murals without fear of bodily harm.

The book’s original one hundred mural prospects have been whittled down to a less expensive, more portable twenty-five. Hazard’s criteria for this process were partly aesthetic. Having completed an undergraduate degree in art history at the University of Notre Dame, she figures that she “knows what looks good.” Her main editorial provision was that the murals had to tell a particular story about a particular place—hence the title Walls That Speak. “Murals,” Hazard informs me, “unlike a lot of public art, really are about the place. They’re site-specific. It’s all tied to local history. A lot of the people in the murals are people who live there.”

This emphasis on neighborhood exploration and explication is really what attracted me to Walls That Speak in the first place. For I must admit that during the six odd years that I have lived here, I’ve found Boston to be a bit hard to read. The only indigenous culture I recall witnessing consists of the noisy congregations that gather in the streets of the Fenway area—oh, and the residing demonic spirit that summons an attitude of distress and exasperation in even the kindest and gentlest of citizens when they enter the area of Coolidge Corner for the primary purpose of retail. Never have I been admitted to the vast, underground currents of communities and connections that exist beneath the unavoidable distractions of bars, restaurants, and bookstores that could be found in any similar city in the country.

Hazard’s murals are all represented in vibrant color photographs with accompanying text that explains the method of painting and the story behind the painting. Most of this explication is done by way of quotes from the artists, all but two of whom Katie Hazard managed to track down (a task much easier than it sounds because many of the muralists know each other). The book also contains an introduction, T directions, and maps.

Hazard’s murals are all represented in vibrant color photographs with accompanying text that explains the method of painting and the story behind the painting. Most of this explication is done by way of quotes from the artists, all but two of whom Katie Hazard managed to track down (a task much easier than it sounds because many of the muralists know each other). The book also contains an introduction, T directions, and maps.

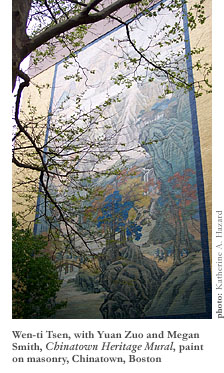

Oh yes, the maps. So there we were in the labyrinth of Chinatown trying to work out where we were on Hazard’s map. The problem was that although her book told us which street we were looking for, there was no information about the adjoining streets. Nevertheless, just as we were about to crumple over in despair, a side street presented itself to us offering if not salvation, at least some shade. Said side street turned into a back alley at the end of which, obscured by trees, reflecting glare from the sun, there stood the paint-on-masonry wonder that is the Chinatown Heritage Mural.

The mural is a copy of a piece in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston by the artist Wang Yun (1652-1735), who painted in the midst of the early Qing Dynasty. The title, Travellers in an Autumn Landscape, aptly describes the scene. Surrounded by orange-, yellow-, and blue-leaved trees, a pack of travelers ascends rough terrain. At the middle of the mural awaits a friendly village full of voluptuous civilization, while at the top a lone figure meditates next to a waterfall that crashes through the middle of the scene. The top, a kind of heaven perhaps, is obscured by mist, and also by the blaring sun that peaks over the top of the adjoining building.

“See,” my associate piped up, “I told you I knew where it was.”

“One down, twenty-four to go,” I replied.

Our next destination was the South End of Boston. Since we had no idea where the nearest T station was, we decided to walk, figuring that since our object mural, Viva Villa Victoria, is housed in the former stained glass window of a former church, we only had to keep an eye out for steeples.

For once, we were spot on. Moreover, the walk was well worth it: Viva Villa Victoria, at 85 West Newton Street (off Tremont Street), was probably the most memorable piece we saw that day. It is also probably the most narrative piece that Hazard includes, telling the history of the mostly Hispanic area’s fight to remain a low-income one in the midst of gentrification, a fight that seems to have ended in compromise if the trendy shops we passed on the way are any indication.

For once, we were spot on. Moreover, the walk was well worth it: Viva Villa Victoria, at 85 West Newton Street (off Tremont Street), was probably the most memorable piece we saw that day. It is also probably the most narrative piece that Hazard includes, telling the history of the mostly Hispanic area’s fight to remain a low-income one in the midst of gentrification, a fight that seems to have ended in compromise if the trendy shops we passed on the way are any indication.

The next piece, On the Wall: Cultural Legacy and Our Latin Pride at Villa Victoria, was around the corner, conveniently located across from an ice cream truck that had been stalled for twenty minutes but continued to allow its jingle to play on, drawing local children and my partner and myself, already in need of refreshment despite the dim sum we had in Chinatown. If the previous piece had told a somewhat tragic story, On the Wall actually embodies a sense of tragedy. A section of it had been torn away and somebody had mutilated the face of the controversial drug addict, who sat in the corner as a moral reminder of the danger of illicit substances.

Next we took the orange line to JP (Jamaica Plain). A long walk down School Street ended with a viewing of Peace Through History, which is a multi-cultural smorgasbord depicting, not surprisingly, Gandhi and Martin Luther King, as well as, less obviously, Malcolm X and even Frida Kahlo. An equally long trek down Centre Street revealed another two multi-ethnic extravaganzas—Lantern Walk, which depicts the annual Halloween trek around Jamaica Pond, and Bella Luna/Milky Way Mural, which represents various local figures including Mary Beth Cahill of JP karaoke fame, resident Pedro Martinez, and a hairdresser from the nearby Ulta Beauty.

Finally, as we rested our feet on a bench at the corner of Eliot and Centre, we cast our eyes towards Vita Brevis, a controversial piece painted, as Hazard informs us, by a group of young painters assembled from the Boston neighborhoods called the Boston Mural Crew. The crew went to work on its own design—which included another rendering of Frida Kahlo—only to be stopped when the community deemed it inappropriate to the history and location. The crew was forced to change the design, but got the last laugh by turning the controversy into the subject of the mural, depicting themselves painting the historical figures.

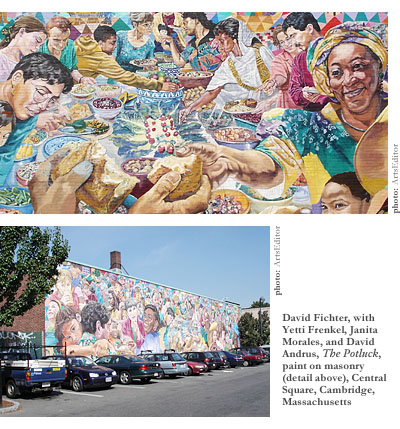

With the day waning and our stomachs starting to rumble again, we decided to finish our tour with the cluster of murals in Central Square. Outside of the T stop, we found three more examples of multi-cultural pieces in Crosswinds, Crossroads, and The Potluck, as well as an oddly-placed mural inspired by Marc Chagall, A Celebration of Imagination, the only work included in the volume that isn’t directly site- or Boston-related.

Finally, we found the Women’s Community Cancer Project Mural at 10 Church Street, Harvard Square, featuring a group of smiling, lounging, kind of cartoonish, cancer-surviving women whose background is a veritable sea of protesters promoting an end to carcinogens. And then we found a table at which to enjoy chips and salsa.

As we ate, we discussed our conclusions. We decided that, as far as a workable volume goes, Walls That Speak is reasonably successful. Some more detailed directions and maps would certainly be an improvement, but what Hazard provides should be enough for a resourceful pedestrian with a basic knowledge of the locale.

As a historical piece, the book does not always provide the most in-depth description of the nature and narratives of the murals’ neighborhoods, but it does at least give enough of a glimpse into those stories to whet the appetite for further exploration.

Aesthetically, we must admit that the book feels a bit tiresome as it heaps multi-ethnic celebration upon multi-ethnic celebration, but then again, that tends to be the subject of many community murals. And with a few exceptions, the murals catalogued are well-crafted, and all of them are beautifully photographed by Hazard.

Walls That Speak is not exactly a book for a daytripper, unless that daytripper has access to wheels and starts much earlier in the day than we did. Nevertheless, for the resident of the Boston area it’s an intriguing, quirky, and enjoyable guide to some of the lesser-known nooks and crannies of their city. Unfortunately, it has not so far engaged the interest of any publisher. However, its inherent qualities, combined with Katie Hazard’s dauntless energy and enthusiasm, suggest it is only a matter of time before it can be found in every Boston bookstore.