“Lyric poets/ Usually have—as he knew—cold hearts./ It is like a medical condition.” -Czeslaw Milosz (1911-2004)

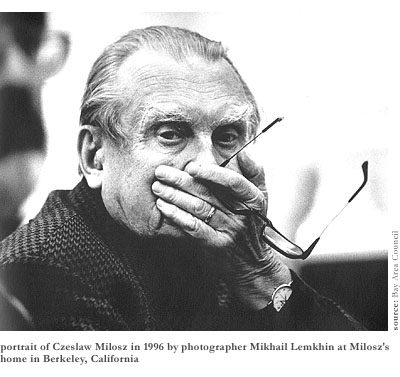

It was Saturday morning, August 14th. Leafing through a May issue of The New Yorker in the passenger seat of the Honda, I came across a poem by Czeslaw Milosz. I’d intended to find a piece my wife wanted me to read to her as she drove us out of town for the weekend—David Denby’s ultimately favorable review of the movie Troy. We’d just finished reading aloud (and to ourselves) the Robert Fagles translation of Homer’s Iliad and wondered if we should see the enacted Hollywood version. But the title of the Milosz poem, “Orpheus and Eurydice,” promised to be relevant to our erudite flirtation with the classics. Little did we know that Milosz, Polish ex-pat poet and professor who’d resided for decades in Berkeley, California, was back home in Poland dying that day.

Translated from the Polish by the polished California golden-boy poet Robert Haas (as always has been the case with Milosz translations into English), the 90-line poem turned out to be worth the detour through Hades. In lean, muscular lines that stressed less metric regularity than the suspenseful elasticity of line breaks, it had familiar Miloszian characteristics, conversationally addressing a grand theme, putting a personal touch to the mythical public knowledge, arresting the attention with immediacy of tone and vividness of detail. It started with Orpheus “on flagstones of the sidewalk at the entrance to Hades”—

…hunched in a gust of wind

That tore at his coat, rolled past in waves of fog,

Tossed the leaves of trees. The headlights of cars

Flared and dimmed in each succeeding wave.

In Jean Cocteau’s film about Orpheus, we’d marveled at the archetypal poet listening to murmurings from the underworld on his car radio before attempting to rescue Eurydice from the underworld. (A decade or more ago, the American Repertory Theatre in Cambridge produced a killer version of Philip Glass’ musical rendition of this story, by the way.) In Milosz’s poem, though, we found Orpheus as a melancholic film noir character, like Humphrey Bogart hoping to rescue Ingrid Bergman.

Early on in the poem, Orpheus descends to Hades on an elevator, as if in a Hitchcock thriller, stopping “at the glass-paneled door, uncertain/ Whether he was strong enough for that ultimate trial,” going down “many floors, a hundred, three hundred down…”

Under thousands of frozen centuries,

On an ashy trace where generations had moldered

In a kingdom that seemed to have no bottom and no end.

Soon, Orpheus encounters “those to whom he had done harm” but “they had lost the ability to remember/ And gave him only a glance.”

Even though he’s a 20th Century existentialist who’d be more likely to play jazz on a grand piano or a stand-up bass, Milosz’s model of the mythical poet “had a nine-stringed lyre” and “carried in it the music of the earth, against the abyss/ That buries all of sound in silence.” As everyone may recall, he has to use the lyre’s magic to charm Persephone, “in her garden of withered pear and apple trees” listening to him play “from the funereal amethyst of her throne,” to let him take Eurydice away. Moreover, he has to sing “the brightness of mornings and green rivers…of smoking water in the rose-colored daybreaks” to win her back. He has to name colors, “cinnabar, carmine, burnt sienna, blue,” and praise “the delight of swimming in the sea under marble cliffs” and “the tastes of wine, olive oil, almonds, mustard, salt.” And finally, foreshadowingly, he must sing to Persephone of “having composed his words always against death/ And of having made no rhyme in praise of nothingness.”

The poem within the poem was turning out to be a delicious experience itself—just the ticket for getting your lover released from Hades—with lines so loaded by luscious words we didn’t wonder how accurately the translation may have conveyed the sound and sense of the Polish.

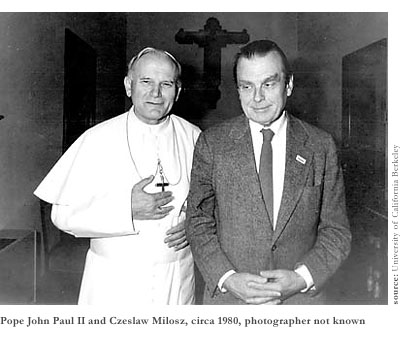

In retrospect, I would wonder whether Milosz, coming as he did from stubbornly Catholic Poland and having given at least one reading that I witnessed in the 1990s to a huge crowd of unlikely literati at stubbornly Catholic Boston College—well, whether he believed more in the mythical Greek hell or the mythical Christian hell, and whether he thought he would be visiting either destination on his death. But at the time, there in the car on the way out of town in August, I remembered romantically that I myself had sung—or muttered anyway—poems to woo someone 20 years before, and saw that now I was reading to her about Orpheus singing to win Eurydice.

Here, then, came Eurydice herself, more than halfway through the Milosz poem, in a trance, led by a guide, her face “no longer hers, utterly gray,/ Her eyelids lowered, beneath the shade of her lashes”—with Orpheus in the lead, granted the return of his love by Persephone as long as he promises not to turn his head “to assure yourself that she is behind you.”

A suitably grim rendering of the old story we’d seen in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the Nobel Prize-winning master’s “Orpheus and Eurydice” seemed graver for its modern setting somehow. But then it took a surprising turn away from the film noir setting when “[a] steep climbing path phosphorized/ Out of darkness like the walls of a tunnel.” Suddenly Orpheus finds himself haunted by a ghostly tapping sound, sometimes “closer, sometimes more distant,” until “a doubt sprang up/ And entwined him like cold bindweed” and he bursts into tears “at the loss/ Of the human hope for the resurrection of the dead,/ Because he was, now, like every other mortal.” Worse yet, “His lyre was silent, yet he dreamed, defenseless./ He knew he must have faith and he could not have faith.”

This, I began to realize, was a very ambiguous poem, on the one hand about the sacrifice of personal inspiration for another’s happiness and on the other about the trading of artistic inspiration for companionship and escape from isolation. I wanted to read it again.

“Day was breaking” up ahead and “[s]hapes of rock loomed up/ Under the luminous eye of the exit from the underground.”

My wife, meanwhile, kept driving straight ahead, not looking over to see if I was still there, listening sympathetically enough to Orpheus’ plight but probably eager to get along to Troy—or to David Denby’s movie review anyway. She would be able to do that soon, because just before the end Orpheus did turn his head and find that Eurydice, heartbreakingly enough, was gone. “Sun. And sky. And in the sky white clouds.” That’s all he had now. The desolate isolation he’d sung to be rid of, now even emptier than before.

And to think, reading this empathic portrayal of a mythic poet from a damp back issue of The New Yorker, and not having bothered to read a Milosz poem in quite some time really, that the poet was actually dying as I read. Too bizarre even for a subtle and sublime poet’s clairvoyant words.

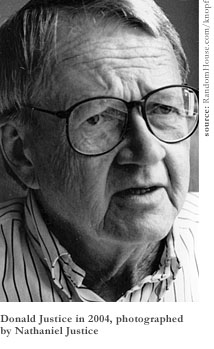

I did know, though, that another poet of note had died a week before, on August 6th, in an Iowa City nursing home. Donald Justice (1925-2004) was his lesser-known name. The papers had printed his obituary already.

In at least one personal way, Justice’s death coincided with Milosz’s. No, I hadn’t been reading from Justice’s spare, melancholy, and technically immaculate collections the day he died. Night Light and Departures and Selected Poems, his books from the 1960s and ’70s that eventually garnered him a Pulitzer Prize, had maintained their alphabetical place on a bookshelf without being disturbed very often for the past couple of decades. And I hadn’t been reading aloud either from whatever terse marginalia he’d scribbled on my own deadline-making poems when I was one of his 30 or more apprentices at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in the very late ’70s. If Justice had crossed my mind much in recent years, more often than not it had been in reference to Dana Gioia, current chair of the National Endowment for the Arts, whose poetry (spare, melancholy, and technically immaculate) Justice liked enough to promote in blurbs on book jackets.

As it happens, the interesting coincidence of these two poets’ passings occurred to me only when I recalled Justice’s own, much more mundane take on the Orpheus myth in the prose poem titled “Orpheus Opens His Morning Mail.” Striking the ineffectual white-guy pose that James Thurber and T.S. Eliot sculpted in the characters of Walter Mitty and J. Alfred Prufrock, Justice begins his funny poem in the time-honored idiom of those demoralized more than immortalized by the tedium of daily responsibility: “Bills. Bills. From the mapmakers of hell, the repairers of fractured lutes, the bribed judges of musical contests, etc…A note addressed to my wife, marked: Please Forward.”

Beyond that missing wife, this Orpheus seeks to rescue no Eurydice from Hades, but finds a photograph from his admirers, in whose rooms he imagines they “must once have locked themselves to read my work”—”barren cells,” at that, with “mullioned panes…through which may be spied, far off, the shorn hedge behind which a pimply tomorrow crouches, exposing himself.” Piece after piece, the mail unfolds a lament about “poe biz”—workshop slang for the less-than-indolent practice of pushing your poetry. Under the junk mail, Orpheus finds “an invitation to attend certain rites” where “I shall probably be asked to recite my poems.” No longer a mystic bard, and far from being a film noir character, this Orpheus suffers the ordinary boredom of the beleaguered, worldly man who reluctantly participates in society. It’s the same compromised householder who ends another funny poem, “The Telephone Number of the Muse,” by musing understatedly, “I have the number written down somewhere.”

Beyond that missing wife, this Orpheus seeks to rescue no Eurydice from Hades, but finds a photograph from his admirers, in whose rooms he imagines they “must once have locked themselves to read my work”—”barren cells,” at that, with “mullioned panes…through which may be spied, far off, the shorn hedge behind which a pimply tomorrow crouches, exposing himself.” Piece after piece, the mail unfolds a lament about “poe biz”—workshop slang for the less-than-indolent practice of pushing your poetry. Under the junk mail, Orpheus finds “an invitation to attend certain rites” where “I shall probably be asked to recite my poems.” No longer a mystic bard, and far from being a film noir character, this Orpheus suffers the ordinary boredom of the beleaguered, worldly man who reluctantly participates in society. It’s the same compromised householder who ends another funny poem, “The Telephone Number of the Muse,” by musing understatedly, “I have the number written down somewhere.”

Known for his interest in applying musical measures to poetry—i.e., for writing in old-fashioned metrics—Donald Justice tended to strike a cool note in his poems, making the most of self-effacement and putting a melancholy touch to sonnets, sestinas, and odes alike. Widely admired for his demanding standards in the writers’ workshops and reluctant to rush things into print, he didn’t encourage prolific writing. He stressed minimalist gray perfection over effusive purple profusion. As he suggested rather strongly in a poem addressed to his students, “There has been traffic enough/ In the boudoir of the muse.”

Frankly, that’s what makes the late poet’s public endorsement of Gioia’s poetry all the more notable—and what makes the implicitly cautious approach of Justice’s poetry seem fitter for times that have drifted further to the right than anyone might have imagined. After all, if the President’s leaguers were to condone any kind of recently produced literature that can’t be found at the airport, it wouldn’t be the chronically clumsy kind of political poetry that Sam Hamill disseminated on his “Poets Against the War” Web site after turning down First Lady Laura Bush’s invitation to the White House the way Robert Lowell more effectively did LBJ’s invitation during the Vietnam War. It wouldn’t even be the courageous and cathartic poetry of witness that is being written by the likes of C.K. Williams and others—poems that take us into public streets and private lives to see the devastations of our culture. It would be the safer, more polite stuff by Justice that the brainier patriotic propagandists would be more liable to read in their drawing rooms and dens.

Be that as it may, it’s not really fair to drag Donald Justice into the chaotic, multicultural melee he avoided so assiduously in his poetry. (Nor, perhaps, to add that Czeslaw Milosz was known to lean pretty far to the right himself after fleeing the totalitarian Soviet Union.) A meticulous and often tender poet from the old school, Justice will be remembered, at least by his nervous students, for a number of graceful poems, including “Men at Forty”—men who “learn to close softly/ The doors to rooms they will not be/ Coming back to.”