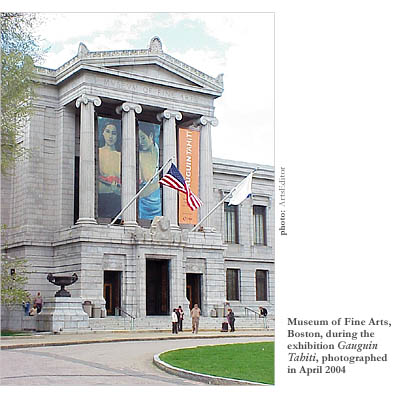

Although the artwork in question offers a vision of eternal summer, the Gauguin Tahiti exhibit, which opened two months ago, will stay in the spare modern rooms of the Gund Gallery in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, only through June 20th—the last day of spring. Maybe it’s just as well, because summer might put to drowsy sleep all the revived feeling that spring will have worked so hard to bring, and Gauguin’s mythical vision of Tahiti might emerge from the shadows of the palms into the bright sunlight and be seen as the fantasy—as opposed to a work of real imagination—that in part it apparently was.

Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) went from Paris to Tahiti to enjoy what he thought would be an actual living paradise—a warm, relaxed, sexually uninhibited place untainted by repressive, authoritarian religion. The touring exhibit, at its only stop in the United States, chronicles his two extended stays there, from his initial arrival in 1891 to his death in 1903, providing plenty of snappy captions along the way that explain the influence of exotic sojourns with his family during his childhood, the restlessness with family and business life in France that he finally surrendered to in his 40s, and his absorbed fascination with animistic myth—or with the atmosphere of entrenched entrancement that meditation on such myth induced. Probably for the best, there’s not much about the famous struggles with Vincent van Gogh in the 1880s that led (maybe) to the latter’s suicide. But there’s plenty about the obvious obsession in his paintings (and to some degree in his three-dimensional wood and clay creations) with the motif of the beautiful young Asian woman. In retrospect, it seems like Gauguin had a terminal case of spring fever that enabled him to work up, in lush paintings that look even better in a bunch of rooms together, a euphoric image of a succulent Edenic paradise—a paradise that didn’t actually exist.

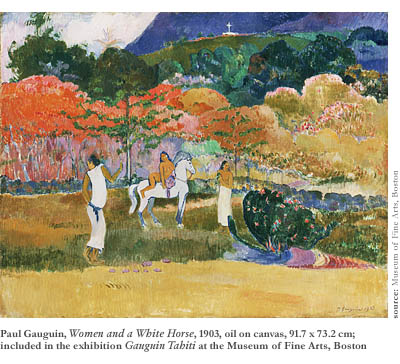

To most museum-goers, the multiple depictions of black-haired, buttery brown-skinned women at rest in various parts of the island paradise will be what would have been expected if someone had ever mentioned Gauguin. That’s the transparent, name-recognition marketing ploy of the exhibition organizers, no doubt, and it’s only the latest in a series of “greatest hits” exhibits that have included Rembrandt, Cassatt, Rauschenberg, and Monet. What might surprise the seasoned, possibly even jaded connoisseur is the cumulative power of the multiple variations on the single motif. There they are, everywhere we look—his bold paintings of round-shouldered, almond-eyed Polynesian women sitting, standing, or lying around alone or in groups of two or three, sometimes with a surprise male guest, often near an allusive fox, not uncommonly near a flat expanse of water and a small settlement of thatched huts under the fan-like palm trees. In guiltless pagan sensuality, not in self-denying grace, the figures wear little or nothing at all—and they almost never look directly at us, because they know we’d just start asking them touristy questions.

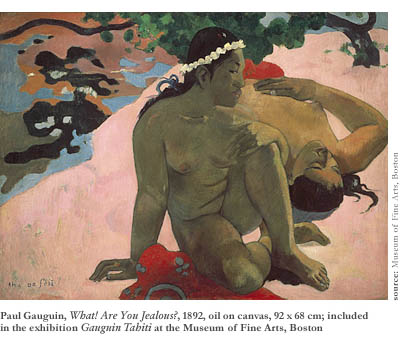

Often Gauguin found—or deliberately and artificially posed—the women in pairs, sometimes by that salty water with that symbolic fox standing nearby, as in Joyousness. Or once in a while in a room with an open doorway showing an allusive horse and rider on the road in the distance, as in The Dream. Or at times disarmingly—and arousingly—close to the surface of the picture, one of them cradling calmly a clay tray of red fruit at her bare breast and looking a little more our way than most of the models, the other holding a bouquet of pink blossoms, as in Two Tahitian Women. And, all too frequently for a buttoned-up tourist, flat-out laid-back on the soft ground of the Pacific Rim, like the two women in the sun in What! Are You Jealous?—one lying back with the eye of her soft face and the eye-like buds of her tender breasts (no tan line visible) equally closed in the sun, the other sitting beside her in a peaceful, private moment of womanly friendship, their warm brown skin a comforting tone amidst the vermilion and Veronese green landscape that Gauguin hoped to endow with the look of “old tapestry.”

Gorgeous as the paintings are, it turns out that Tahiti had been spoiled by the time Gauguin arrived—and the exhibition’s captions are there to say so. According to the no doubt credible word of the curators, Gauguin reconstructed the original before-the-fall condition from the ruin he believed the French missionaries had made of things. Apparently, in 1891 our Margaritaville cruise ship or Peace Corps kayak would not have been greeted at the dock by unclothed creatures who’d never known the joys of committing any very original sins. The captions don’t go into detail about it—but the real people who posed for Bathers at Tahiti in reality may have been members of the first generation of Tahitians to feel ashamed of their nudity as they waded into the lazy estuary. If, before the French colonization, they would have been content to wear the sarongs of Delightful Day and the loincloth of Vairumati, they probably would have been as content to wear the minimum of disguise in their serene and discreet expressions as well—as true in the many portraits of women in pairs as it is in the fabulous Three Tahitians or (one of a few solo portraits) Woman with a Mango.

Paul Gauguin, ahem, must have been very good with his hands, because not only do his paintings demonstrate a seamless application of paint that results in broad bands of bold color expressionistically representing elements of the figure and the landscape—his wood and clay works are wonderful as well. Mixed in with pieces of anthropological booty—wood figures and sculptural ceramic vessels created by the colonized artists and confiscated from Tahiti, some embarrassingly reminiscent of cheesy Polynesian restaurants you’d find along the strips of our own spoiled paradise—Gauguin’s sculptural work makes no bones about his appropriation of the originals. They’re transformational emulations, though—jars alive with the horrifying faces of animistic death spirits or the soft and thick bodies of women, and wood-relief works, hung on the wall in small groups apart from the paintings, featuring the furious, unleashed expressions of spirits amidst the wild jungle growth that gave birth to them. In Head of Tehura and Standing Female Nude, Be Mysterious, and Idol with a Shell, there is less resemblance to any known Western art of its time than there is in the paintings that shared traits with their contemporary Cézannes and Van Goghs. For that reason partly, and partly because his three-dimensional work is not as well-known as his practically iconic paintings, there’s a potent element of novelty to the exhibit organizers’ inclusion of wood and clay. Homages to the animistic myths that apparently had been subdued by the priests, the objects breathe with palpable force in the spare museum space, the mythical figures of folk and fruit seeming to emerge from the deeply polished reddish-brown wood and hand-worked clay with unchecked visceral force. There will be no priests “binding with briars/Their joys and desires,” to the indignant horror of William Blake’s spirit, as Gauguin observed there already had been for the survivors of the colonization.

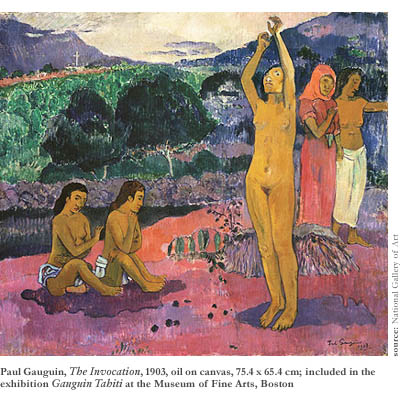

Making aesthetically sophisticated variations on the primitive motif for several years, Gauguin worked, before and after a brief return to Paris, toward the culmination of his fantastic reconstruction of the Tahitian paradise. During 1897-98 he made the masterpiece that the Museum of Fine Arts has owned since 1936—Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?—and in the months leading up to the making of this portable fresco, Gauguin did studies for the piece that are on display in the same room of the exhibition as the masterpiece itself. Afterwards, when the elements of his paradise had all been put together on the one wide picture plane, he made some more paintings, at least one of which borrows from the masterpiece. The Invocation, from 1903, features the same style of painting, in form and color so solid that it, like his work in general, had “the dull, muted, powerful sound” he wanted, of clogs that “echo on granite ground.”

In the masterpiece, which sensually hungry visitors to the Museum of Fine Arts’ famous Impressionist rooms have been gazing at open-mouthed for decades, Gauguin brought together elements from his previous works—the allusive dog, the brooding, darker-skinned spirit, the indolent woman in the blue loincloth, the child in the foreground near the cats, the two young girls talking in front of the hut. They sit and stand apart for the most part, but they all serve to highlight the central figure of the painting, the androgynous, black-haired, lean one in the loincloth who reaches to pick from a branch at the top of the picture a piece of very symbolic fruit. Not your ordinary mango, but fruit from a tree that Paul Gauguin, a Romantic in love with the myth of the noble savage, may be suggesting was not even indigenous to the ecosystem of Tahiti—the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.